Krauthammer's 'The Point of It All' out in December

Daniel Krauthammer finishes his father's final book.

Charles Krauthammer was my father. Writing that sentence in the past tense is still a shock to me, and it evokes a sadness far too deep to express in words. My father and I were very close. I feel the pain of his absence every day, as does every son who loved his father. There were a thousand secret private things between us that I alone know and that I alone will miss.

But my father belonged not only to me, but to so many more: his friends, his colleagues, his readers, his viewers, the country and indeed the world. He played a large role in the political life of this nation, and though he was far too self-effacing to say so himself, his thinking, his ideas and his convictions shaped generations of political thinkers.

Charles Krauthammer with his son Daniel at RFK Stadium in 2007. (Courtesy of the author)

Policymakers and politicians in Washington read him, listened to him and often took their lead from him. But my father did not write solely for the cognoscenti and the power brokers.

He always told me that he wanted to write and speak so that anyone with intelligence and interest could grapple with and benefit from his arguments. He believed in Einstein’s (apocryphal) dictum that “if you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” That, I believe, is the root of his extraordinary popularity. He didn’t talk down. He thought that unnecessary complexity and heavy-handed erudition got in the way of true insight and knowledge: “You don’t want to talk in highfalutin, ridiculous abstractions that nobody understands,” he said. “Just try to make things plain and clear.” He wished to express the truths he saw in the most universal, accessible, concise and convincing way that he could.

He felt a responsibility to his readers and viewers and, beyond that, to history itself. As he put it:

I left psychiatry to start writing . . . because I felt history happening outside the examining-room door. That history was being shaped by a war of ideas and I wanted to be in the arena. Not for its own sake. I enjoy intellectual combat, but I don’t live for it. I wanted to be in the arena because some things matter, some things need to be said, some things need to be defended.

Charles Krauthammer with wife Robyn and son Daniel at Kennedy Center, Pro Musica Hebraica Inaugural Concert 2008.

My father was not just going through the motions. He cared deeply about everything he said and everything he wrote. He knew it would play a part in the discourses that shaped real policies, affected real people and determined the future of the country he loved. He did not take that responsibility lightly. In a 2013 interview, he described the sense of duty he felt to pursue his vocation with the highest order of integrity: “You’re betraying your whole life if you don’t say what you think – and you don’t say it honestly and bluntly.”

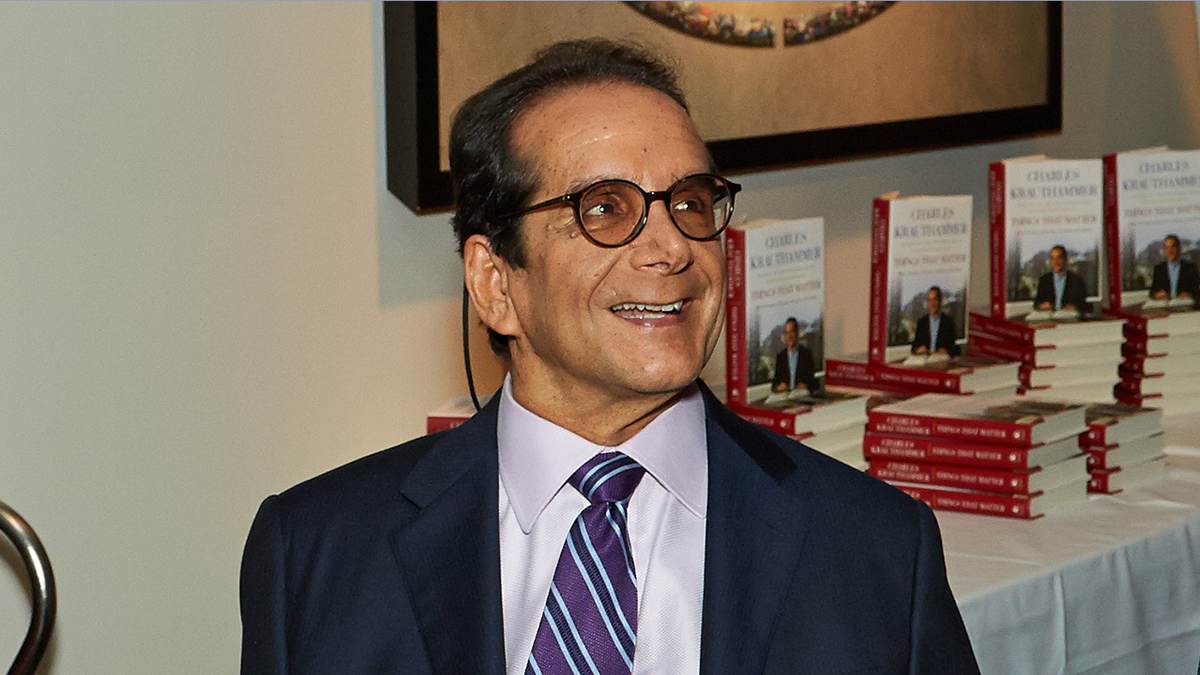

Charles Krauthammer at his book party for "Things That Matter" in 2013. (Fox News)

But his was a quiet sense of duty, one he never wore on his sleeve or shouted from the rooftops. He did not like to talk about himself, especially in public and in his writing. “I’ve never wanted to make myself the focus of my career,” he said in a 2013 interview. “One of the things I aspire to in all of my columns is I try never to use the word I . . . to me every time you use it, it’s a failure . . . I’d rather let the words speak for themselves.”

He wanted his arguments to stand on their own regardless of the speaker. That came from a profound sense of humility, I think – a humility stemming from his own awareness of how little anyone truly knows in the grand scheme of things.

Over nearly four decades of working in and writing about politics, he earned a place unique to only a few political commentators in modern history. He was respected by those who agreed with him and those who did not. He was too humble to ever fully embrace it, but he earned the right – as few have – to draw on the power of his own character in making his arguments. And while he eschewed any privileged place due to his standing, others did not. Sometimes the word of a respected and honest voice matters.

That is why I have included as entries in this book some of the very few occasions, in both articles and speeches, where my father spoke entirely in the first person, imparting his beliefs, his thoughts and his wisdom directly from his own experience to the audience. They reveal something of the depth and strength of my father’s character, the clarity of his own moral principles and the essence of what he felt truly mattered in life – and, of course, his great sense of humor.

When my father wrote about the majesty of the cosmos or the elegance of a chess move, I felt the reality and the weight of their beauty. And when he wrote about the importance of democratic institutions in the face of tyranny over the mind, I felt a deeper meaning to politics that is all too often lacking in our day-to-day debates. By intertwining art and politics in this way – in both the style and content of his writing – he elevated each of them to a higher level.

In "The Point of It All," as in "Things That Matter," my father applied this worldview to a breathtaking range of subjects: not just foreign policy, not just domestic, not just social issues, not just issues of art and taste. To everything. And all of it animated by common principles that give it both enlightening reason and moving beauty. His writing broadens one’s thinking and stirs the emotions and shows their essential connection. That is why I think his books will last far beyond the immediacy of today’s politics. This is the kind of book I imagine a parent would give to a child 10, 20, 30 years from now and say, “Here. This is a book that will make you think. And make you feel. Read it.”

Adapted from the introduction to Charles Krauthammer’s posthumous book, "The Point of It All." Daniel Krauthammer is the author of this excerpt and is the editor of the book. Reprinted from "THE POINT OF IT ALL: A Lifetime of Great Loves and Endeavors" Copyright © 2018 by Charles Krauthammer. Published by Crown Forum, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC