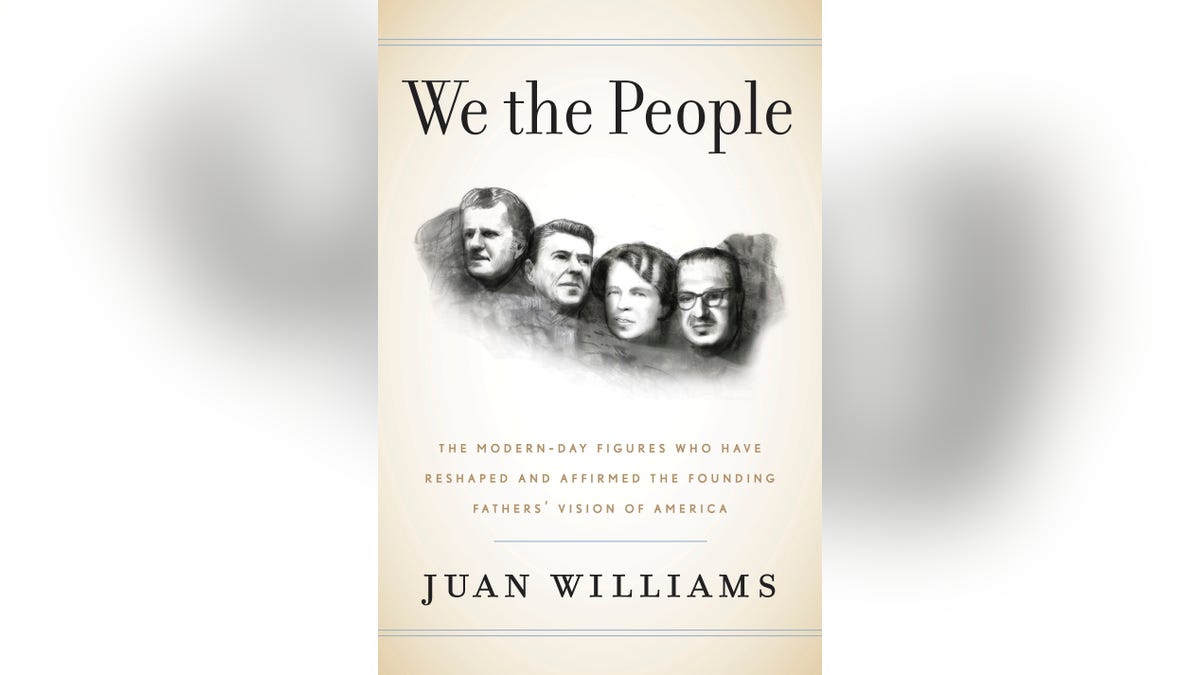

Editor’s note: Dana Perino, co-anchor of “The Five” recently read the new book, “We the People,” written by Juan Williams, her fellow co-host on “The Five.” She highly recommends the book and says it is an insightful and thought-provoking read. She recently sat down with Williams to talk with him about the book.

DANA PERINO: Where would you rank women’s movement in terms of disruption and impact on U.S. society?

JUAN WILLIAMS: To me, the woman’s movement is the most startling change of the last 230 years. Obviously the end of slavery and the demographic shifts in the American family have rocked the country.

But stop and think about the women you know, the women I know and compare them to the women who were known to the Founding Fathers. My wife and mother-in-law both have Master’s Degrees; my daughter and sister are both lawyers; one niece is a Yale Law school graduate who now prosecutes crimes in Washington, D.C.; another niece is a medical doctor; and my sister-in-law helped to run a winning state campaign to help elect President Obama.

The positions that these women now occupy would have been impossible without Elizabeth Cady Stanton, early pioneer for women’s rights who helped compose the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments.

They wouldn’t have been able to get so far if it weren’t for Carrie Chapman Catt, who headed the fight for the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. And, in particular, it would be impossible without Betty Friedan, whose 1963 book “The Feminine Mystique” got women to fight against their limited roles as housewives and mothers.

It is the result of these and countless other pioneering women, who inspired women to go to work and marry later so that they could build careers first.

It is the reason they fought for the right to control their own healt

That has had a tremendous impact on family life, with fewer marriages taking place, more children born to single women and more poverty for those children.

Women also now make up the majority of college and graduate school students, three members of the Supreme Court, 20 percent of the Senate and a record 87 members of the House. And it is the reason why women now make up almost half of the work force.

It is the reason why it is so outdated to judge women by their appearance as opposed to their intellect and character.

DP: On a whole, would you say that the Constitution has held up since the nation’s founding?

JW: I do – it is an incredible achievement for anything to last close to 230 years. When a framework for government can withstand civil war and world wars it stands as an incredible achievement.

When you look past all the noise of politics, past the current presidential race and its 24-hour news coverage, you’ll find a government that still operates by the guidelines set forth in the Constitution.

You’ll see a legislature that makes laws, a judiciary that interprets them, and a president that enforces them.

You’ll see separation of powers, checks and balances: a president that can veto a bill, but a Congress that can override the veto; a president that can lead the nation, but a Congress that can still impeach him; a president that can appoint a Supreme Court Justice, but a Congress that can turn down his appointment.

So, even as we decry all the excesses and distraction of modern political culture, we need to remember that the building blocks of contemporary government – things we still do – are all written, right there, in the Constitution.

Yet in some ways the Constitution has not stood the test of time. And that’s a good thing. The men who wrote the Constitution would never have understood something like the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or the Voting Rights Act of the following year. In their day blacks were three-fifths of a person. They did not fight to end slavery. And they allowed the slave trade to continue for 20 more years.

It was Thurgood Marshall who once called the Constitution “defective from the start.” So, in part, it is a good thing that the Constitution included the ability to be amended.

When the 55 delegates were gathered in 1787 to write the Constitution, they didn’t make their debates open to the public. They wanted to be able to disagree candidly, without the fear that their words would be used against them. They wanted to disagree, which they did—a whole lot – before reaching compromise. That was the spirit in which the Constitution was written. So, the fact that we’re still fighting may prove just how constitutional America still is.

DP: What is the next big change and who might lead it?

JW: Option 1: As a black man, one of the most emotional parts of the book to write was the chapter on race. The rapid increase in racial minorities in the USA and immigrants is changing the national character. It is no longer solely focused on black disadvantage and white responsibility for slavery. The conversation is far more nuanced with the problems of racial inequity often focused on the black poor and their mistreatment by the police.

But there is a bigger story about race emerging.

In the book I focused on two figures – Martin Luther King and Jesse Jackson – who defined the race question of their era. For King in the mid-20th century, it was a question of black citizenship: earning the right to vote and enter white-owned establishments. For Jackson, in the late 20th century, it was a question of black capitalism: better jobs, better pay, and more political power to demand equity.

But what issue defines the race question today? I think it comes down to education and ending the achievement gap between black and white students.

Incidentally, it was while I was editing “We The People” that Donald Trump called for a wall between the United States and Mexico and claimed Mexico was sending thugs, rapists, and drug dealers to the United States: inflammatory remarks that has made immigration reform a key talking point in the 2016 election season.

I thought about my chapter on the Kennedy Brothers – John F. Kennedy and Senator Ted Kennedy – whose Irish heritage inspired them to lobby for immigration reform, leading to the passage of the 1965 Hart-Celler Act. They did this by assuring Congress that immigration reform was in keeping with America’s best principles: that we’d always been a “Nation of Immigrants.”

Based on the amount of time politicians have spent on immigration during the election season, I think one major change -- fast approaching -- will involve immigration reform. It will come from someone who can find a way to provide a path to citizenship for the 11 million undocumented immigrants currently on our shore, while ensuring Republicans that the border will become secure. And it will come from someone who can convince America that immigration reform is in keeping with America’s best principles of inclusivity.

Perhaps it will be someone like Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D-Ill.), Chairman of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Immigration Task Force and longtime advocate for immigration reform who authored the Immigrant Children’s Educational Advantage and Dropout Prevention Act in 2001 (never went to a vote), a precursor to the DREAM Act.

Or maybe the current meltdown of the Right (caused by Cruz and Trump) will allow the moderate Republican voices on immigration to take control of the immigration question. Maybe it will be someone like Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart (R-Fla.), a Republican of Cuban heritage and an important advocate for a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Or maybe someone like Senator Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.), a former member of the Gang of Eight who has also argued for a pathway to citizenship.

DP: As a journalist, if you could go back, what would you have liked to ask the Founding Fathers?

JW: Question for the Founders in General: How long do you think this republic will last? According to Yale historian Joanne Freeman, Americans well into the 1790s made offhand comments in their letters to one another like: “If this government lasts more than five years, here’s what I think we should do.” So I would ask them how much faith they had in the government that they were making. How long would it last? What would have to happen in order for it to last? Were they ever suspicious that it would fail as soon as it began? Who’d be responsible for the failure?

Some Questions for George Washington: Many believed that George would remain president until he died. But he did not. By stepping down from the presidency in 1796, Washington set the two-term precedent. He said he was tired and worn down by the job. His decision to turn down a third term has also been read in symbolic terms; the US is a democracy with presidents, not a monarchy with Kings. Mr. President, off the record, why didn’t you take a third term? What were the competing interests? According to historian Ron Chernow you “had always planned to remain as president only until the new Constitution had taken root.” (Ron Chernow’s words) But did you ever hesitate? Did the prospect of a third term ever seem appealing?

Some questions for the loyalists: We tend to forget that not every colonist wanted to rebel against the mother country. But not every American Colonist was so set on starting a revolution. Some were loyalists. In fact, 15 to 20 percent of white male colonists during the Revolution remained loyal to the crown. Another large percent just didn’t want anything to do with the war. Loyalists were not all stuffy aristocrats. Some were regular old farmers. I’d want to talk to them. I’d ask them what they thought about the patriots? What did they think about the Crown? What was their reasoning for not joining the cause?

DP: All the changes that the US has been through can lead us to new beginnings. On the other hand, Trump is talking about returning to something that we’ve lost. Is there some leader that can unite the people who want to go back and the people who want a new start?

JW: That’s a difficult question. But here are some ideas:

Someone in the Tech Industry: So I didn’t cover this in the book, but when I think about the companies you hear most about today, and when I think about millennials, I realize that it’s all about tech. People like Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, Sergey Brin, cofounder of Google, Jack Dorsey, founder of Twitter, and Kevin Systrom, founder of Instagram. Everyone respects the work that these tech hotshots have done: no matter your political persuasion. They’ve been able to tap into America’s long history of capitalist innovation, as well move America into the future technologically, radically changing the way we communicate, hold campaigns, and run government. Some of them are huge philanthropists. Some, like Zuckerberg, have been active in, among other areas, education reform and disease research. I wonder whether any of these or other tech figures will enter politics in earnest.