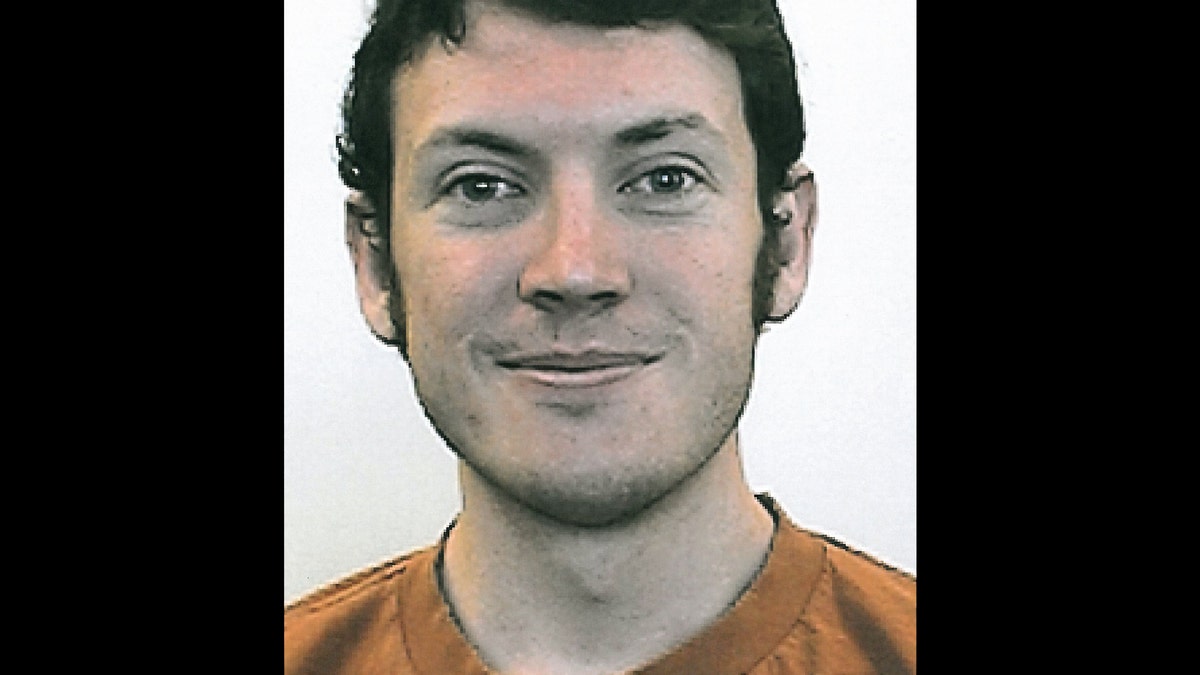

This photo provided by the University of Colorado shows James Holmes. University spokeswoman Jacque Montgomery says 24-year-old Holmes, who police say is the suspect in a mass shooting at a Colorado movie theater, was studying neuroscience in a Ph.D. program at the University of Colorado-Denver graduate school. Holmes is suspected of shooting into a crowd at a movie theater killing at least 12 people and injuring dozens more, authorities said. (AP Photo/University of Colorado) (2012 AP)

The case of James Holmes, the man who killed 12 people in Aurora, Colo., and injured dozens more, has absolutely nothing to do with the availability of guns. Such individuals -- twisted or hobbled by disorders of the mind -- can always find ways to turn the demons that haunt them inside-out, projecting their terrors on the world around them.

If Holmes hadn't shot people with an assault rifle, he would have blown them up with makeshift bombs or sprayed gallons of acid into the faces of children or ignited an inferno in a hotel.

I lost a friend to murder several years ago. He was run down by a mentally ill doctor who accelerated to 60 mph, aimed straight for my buddy, who was jogging in a park at the time, and plowed his car into him, crushing his skull. He had no gun. The two men had never met.

The case of James Holmes has everything, however, to do with the fractured, fragmented, anemic state of psychiatry in America and our unwillingness to educate the public how to recognize symptoms of mental illness and what to do when those symptoms are identified.

Because, in the end, it will become clear that more than one person -- and probably several, including family, friends, neighbors, classmates, health care personnel or educators -- knew or should have known that James Holmes was confused, losing sight of reality, experiencing severe mood swings, withdrawing from the world around him, experiencing violent fantasies or all of the above.

Most people -- even high school guidance counselors, college educators and family physicians -- remain mystified what to do if a person is acting bizarrely, has expressed thoughts of being violent or is voicing paranoid ideas or responding to voices commanding them to wreck havoc on others. They don't know that they can call 911 or that they can call their local police. They don't know that they can petition a district court to commit a loved one to a psychiatric facility. Many have no idea that their communities are covered by mental health centers with crisis teams that are duty bound to respond to such matters by at least considering the possible risks or evaluating the individual in question.

People who wouldn't hesitate an instant to intervene on behalf of someone who has a seizure or experiences chest pain, seem paralyzed to intervene on behalf of those who are mentally ill and experiencing even the most severe symptoms.

Deploying a national public information campaign, perhaps titled “MY BROTHER'S KEEPER,” about what to do when someone appears to be in the grip of mental illness -- and unwilling or unable to get help -- would go a long way toward preventing tragedies like the one in Colorado.

Still, the campaign would have to be married to a tandem and very aggressive project to close the gaping holes in the safety net that keeps the mentally disordered from falling too far -- sometimes with tragic consequences. Because many police officers remain unclear how much discretion they have to convey troubled people -- even people with violent thoughts or intentions -- to emergency rooms. Many teachers wrongly believe that they have no right to approach students and their families with concerns about violent writings or art. And, believe it or not, many mental health personnel see the mental health care system as so complex, and so stretched, that they are loathe to deploy even the meager resources that exist within the courts and our gutted state and private psychiatric hospital system.

Some of what should be done seems obvious. The fact that the University of Texas at Austin; Columbine; Virginia Tech I; Virginia Tech II and, now, Colorado, involved assailants who were students or were recently students argues for strategies to identify the mentally ill on campus. Students in grade school are required to show evidence of immunizations. Would it be too much to expect high school students to sit for tests designed to identify severe psychopathology? If we care whether our kids are exposed to tuberculosis, shouldn't we care if they are exposed to people struggling with voices, visions or paranoia?

If students show up at university health services for physical examinations and medical histories and there is no evidence that they were screened for psychiatric symptoms, and tragedy ensues, shouldn't colleges be liable for the fallout?

My professional life as a psychiatrist has been spent gaining more and more respect for the power of psychiatry to heal people, while watching the profession itself become a shadow of itself, partly due to the ineffective, misguided leadership of the American Psychiatric Association and other bodies that we entrusted to deploy our resources to the public good.

Now, it is time to do so in a strategic, sensitive, comprehensive way that can reduce psychiatric suffering and psychiatric stigma, while safeguarding the public from the worst symptoms of psychiatric disorders.

Now. because for dozens of people in Aurora, Colo. -- and hundreds of their family members and friends -- it is already too late.