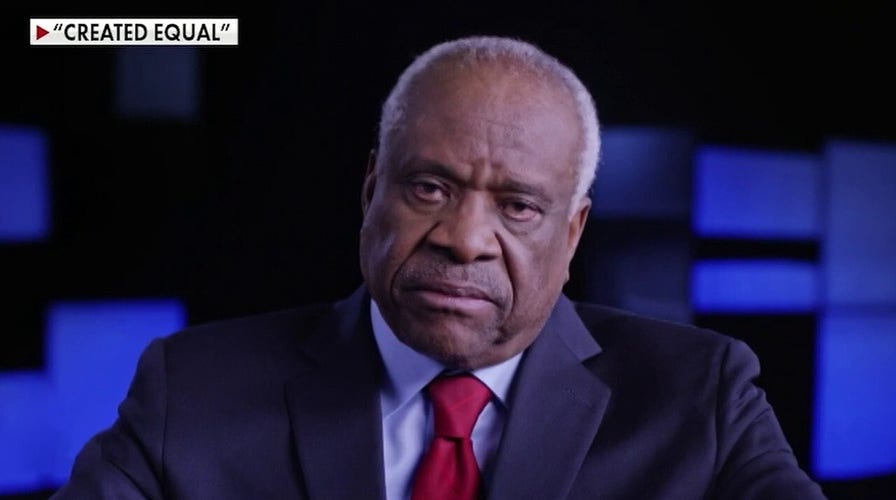

Clarence Thomas issues timely warning in new documentary amid Biden allegations

Michael Pack, director and producer of 'Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words,' joins 'The Ingraham Angle' to explain.

Get all the latest news on coronavirus and more delivered daily to your inbox. Sign up here.

Many today seem to revel in their victimhood, whether it be based on race, gender, sexual orientation or class. Many have good reason, none better than African-Americans, whose ancestors suffered centuries of slavery, followed by Jim Crow, lynchings and discrimination.

But, how useful is it to base your identity on being a member of a victimized group?

The life of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas provides an answer. I learned this first hand, interviewing him (and his wife, Ginni) for over 30 hours as part of a new documentary called "Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words," which will be nationally broadcast on PBS on May 18.

TREY GOWDY: WHY FAIRNESS MATTERS — ALWAYS

Clarence Thomas had good reasons, all his life, to see himself as a victim. He grew up in the segregated South and suffered real poverty and hunger when very young. In high school, when he entered an all-white seminary to study for the priesthood, he was the occasional butt of racist jokes and slurs.

When, as a young lawyer, he went to work for the Reagan administration, the civil rights establishment considered him a race traitor; journalist Hodding Carter called him one of those “chicken-eating preachers who gladly parroted the segregationists’ line in exchange for a few crumbs from the white man’s table.”

More from Opinion

His bruising confirmation battle to become a Supreme Court justice, including sexual harassment charges by Anita Hill, ratcheted up the attacks by his enemies. These attacks continue up to the present day, often employing racist tropes, such as picturing Thomas in KKK robes or as a shoeshine boy.

For a while, Thomas did see himself as a victim. In his college years at Holy Cross, during the tumultuous '60s, he and others in the Black Student Union supported Malcolm X, the Panthers, and, as he says, “anyone who was in your face.”

Thomas says, “Racism and race explained everything.” Finally, during an anti-war rally at Harvard that became a near riot, he was shocked by the violence he felt welling up in him, until he found himself in front of the chapel at Holy Cross in the middle of night, asking God, “If you take anger out of my heart, I'll never hate again.”

At that point, Thomas returned to the values of his grandfather, Myers Anderson, who had raised him since he was 8 — the values of self-help, of “do for yourself.” Anderson’s favorite saying was “Old Man can’t is dead. I helped bury him.”

Clarence Thomas' grandfather had every reason to think himself a victim: illegitimate, illiterate, grandson of a slave, working from “sun to sun” on an oil truck to make ends meet. But he did not see it that way.

Anderson had every reason to think himself a victim: illegitimate, illiterate, grandson of a slave, working from “sun to sun” on an oil truck to make ends meet. But he did not see it that way.

He saw himself as a self-supporting, proud black man who was raising two grandkids. Although Anderson was a supporter of the NAACP, he did not look to the government for help, just for his rights.

Later, Thomas would trace this attitude, once common among poor blacks, to Frederick Douglass, whose portrait is behind his desk at the court. Thomas began his opinion on an affirmative action case with a famous Douglass quote: “If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are worm-eaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall! … And if the negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone!”

Thomas also traces these ideas to Lincoln and, before him, to the Founders and their ideas of natural rights, which are spelled out in the Declaration of Independence and protected by the structure of government in the Constitution.

As he says in the film, “They start with the rights of the individual, and where do those rights come from? They come from God; they’re transcendent. And you give up some of those rights in order to be governed. They’re inalienable rights. And you give up only so many as necessary to be governed by your consent.” His jurisprudence, his originalism, is based on these ideas.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

Clarence Thomas has called his grandfather “the greatest man” he has ever known. His grandfather could have lived his life full of resentment, wallowing in his victim status.

Instead, he lived as a free, proud and independent man, striving to create a better life for his grandchildren. Clarence Thomas has chosen to live his life that same way. All of us, perhaps with fewer challenges, face the same choice.