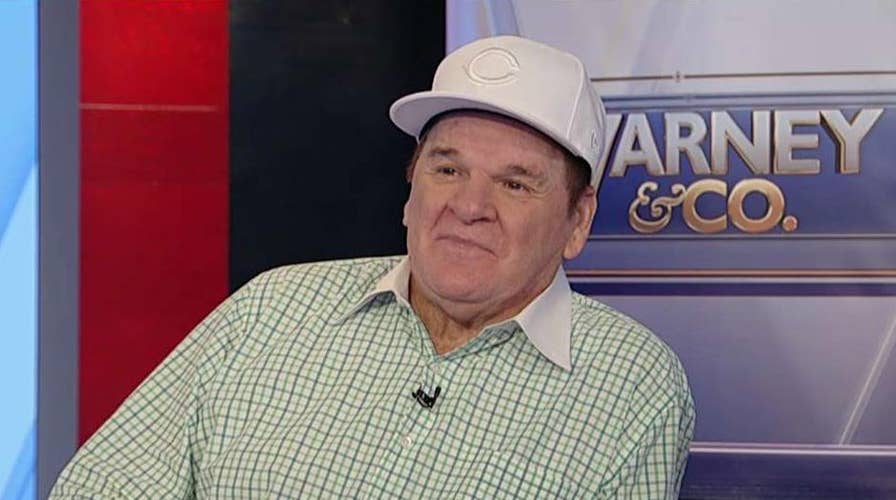

Pete Rose on the Baseball Hall of Fame: I'm not angry, I'm the one that screwed up

Baseball legend Pete Rose on his career in baseball, the Baseball Hall of Fame and President Trump.

It could have been 1977, 1987, 1997, 2007 or 2017. But this was just a few days ago – Thursday night.

I pulled into the driveway of my home in Alexandria, Va. The antiquated, muddy, AM radio wave ricocheted off the ionosphere. It struggled to reach the equally antiquated car radio in my 2004 Toyota. The signal popped and crackled. The sound wafted in and out like a Caribbean tide.

But if you were conversant in the lingua franca, you knew exactly what you were listening to. Every few seconds, a few words breached through the miles.

MARTY BRENNAMAN ON FINAL GAME: ‘HARDEST DAY OF MY LIFE’

“The batter now…

“Aquino, back in the first…

“….second base…”

“…Milwaukee...dugout…”

More from Opinion

This was the final Cincinnati Reds radio broadcast of Marty Brennaman. A game between the Reds and Milwaukee Brewers. For 46 seasons, Brennaman has been the voice of the Reds. His first year in the booth was the first year I was old enough to remotely pay attention to baseball.

But then came the legendary Reds clubs of 1975 and 1976. The Big Red Machine. Arguably the best teams ever assembled in the game. And everyone was paying attention, regardless of their age.

I learned baseball from three people. My dad, my grandpa and Marty Brennaman.

Dad would hit hot grounders to me in the backyard at our home just outside Jacksonburg, Ohio. I’d field them with a thin, Clete Boyer glove that Dad used back in the 1950s. Dad once described to me how badly he got hurt being hit by a pitch by Joe Nuxhall’s brother during a pickup game in Hamilton.

AND THIS ONE BELONGS TO MARTY: BRENNAMAN CALLS FINAL GAME

My grandfather lived next door. He would regale me with stories about Earle Combs, a Hall of Fame outfielder for the Yankees back in the 1920s and ‘30s who grew up not far from his home in Kentucky.

Then there came tales about Charlie Root, who pitched for the Cubs and grew up just down the road in Ohio. Root is best known as the pitcher who was on the mound for Chicago when Babe Ruth “called his shot” in the 1932 World Series.

Finally, there was Marty Brennaman.

It didn’t matter whether we were talking about the 1976 Reds – with the great Pete Rose and Johnny Bench – or the revolting 1982 Reds, stocked with the likes of Paul Householder and Rafael Landestoy. Marty was who I heard, all summer long.

And, for the record, even though I have only had three brief encounters with Marty, any Reds fan just calls him “Marty.” Everyone knows who “Marty” is.

It like Bono. Pele. Cher. Oprah. Adele.

And Marty.

I recall sitting on the edge of my bed, up way past my bedtime on September 20, 1977. The Reds were in San Diego. Dad said I could listen to the Reds bat in the bottom of the first before going to bed.

I listened intently as George Foster cracked his 49th home run of the season, en route to 52. Marty had the call. Dad asked me: “Do you think he can crack 50?” But then it was bedtime.

I can tell you where I was in our living room on June 16, 1978, listening to Marty call the final out of Tom Seaver’s only no-hitter. We rushed home from my own knothole league game, listening to the 7th and 8th innings on the radio.

I can describe my shock listening to Marty during the second game of the 1990 World Series between the Reds and A’s. I was sitting with a friend high in the center field seats at Riverfront Stadium.

The game went into extra innings. I scored the game and listened to Marty on a Sony Walkman. Suddenly Marty made a strange request over the air for Reds pitcher Tom Browning to come back to the ballpark.

Browning’s wife had gone into labor and he apparently headed to the hospital. This was before mobile phones and emails and text messages. The Reds had burned through their pitching staff and worried they might need Browning to pitch if the game went on much longer.

The only way the Reds could reach Browning was through the sound of Marty’s voice, in hopes he was listening.

The Reds prevailed in the bottom of the 10th and Browning’s services weren’t needed.

I learned baseball from three people. My dad, my grandpa and Marty Brennaman.

I’ve been in Washington since 1993. I’ve always had a pre-selected button on my car radio for 700 kHz. That’s WLW-AM in Cincinnati. WLW’s carried the Reds games for decades. It’s the only station in the U.S. that ever broadcast at 500,000 watts.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt flipped the switch to jack up the power from the White House in 1934. Today, WLW boasts a 50,000 watt “clear channel” signal. The station is known for a legendary transmitter located off Tylersville Road, north of Cincinnati. It’s just a mile or two from the home of former House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio.

If you live outside of Cincinnati and want to hear the Reds late at night, chances are you can pick them up on WLW anywhere in the eastern United States. The station boasts that it reaches “38 states” at night. That’s true, depending on the weather and cloud skipping. And this is how I have mostly listened to the Reds at night, driving home from work in Washington.

Lots of sportscasters are known for signature catchphrases.

“How about that?” by the Yankees’ late, great Mel Allen.

When it was clear the Los Angeles Lakers had things in hand, play-by-play man Chick Hearn would indicate they “put the game in the refrigerator.”

When the Washington Capitals defeat an opponent, whether it be the Canadiens or Flyers, John Walton always says “Good morning, good afternoon and good night Montreal (or Philadelphia, or whomever).”

Marty was known for his pronouncement “and this one belongs to the Reds” at the end of every Cincinnati victory.

There’s something romantic about a tagline like that. But for me, the line I always remembered from Marty is “there’s a drive……”

It didn’t matter if it was George Foster in the 1970s, Dave Parker in the 1980s or Eugenio Suarez today. There was just a way that Marty would utter that phrase.

“There’s a drive…”

You’d hear the crack of the bat. And then Marty’s pitch would dramatically rise with the din of the crowd.

“There’s a drive … deep left center field ….”

When you heard Marty say “there’s a drive” the Reds were about to do something great. That call was shorthand. It wasn’t a home run – yet. But with Marty’s astute eye and voice, you knew it soon would be.

Those three words – and just the way Marty said them – were a theatrical tease. Maybe it wouldn’t be a home run. Just a long fly ball to the warning track.

Those words filled with anticipation the few seconds it took the ball to clear the fence. You could see the “drive” rocketing toward the wall, be it Riverfront Stadium, Wrigley Field or Candlestick Park.

That expression may have been the most intimate in Marty’s broadcast repertoire. Only those who listened regularly knew the little secret. It was going to be a home run. But he just injected the drama into it. Rarely was Marty wrong on such calls.

Marty’s last game was Thursday afternoon in Cincinnati against the Brewers. Not a night game. Naturally, I was stuck at the Capitol, covering impeachment. I didn’t get to hear any of the game live. And since it was an afternoon game, WLW’s signal wouldn’t have reached Washington until the sun set.

Nightfall is when AM signals start skipping off the clouds and ionosphere. People in New York hear stations in Detroit. Listeners in Detroit tune in stations from Nashville. If things weren’t so busy on Capitol Hill, I could have listened to a crisp broadcast online. But what’s the fun in that?

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR OPINION NEWSLETTER

So I turned on the rebroadcast as I drove home. The signal wasn’t great. WLW is known for its distinctive, diamond-shaped, Blaw-Knox tower, piercing the sky north of Cincinnati. But reception was spotty.

I could only hear a few of Marty’s words. Then, a wall of electronic interference would fill the frequency before dissipating.

Just a few lines here and there.

“… the right-hander.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“… Castillo sights the sign …”

“… Joey Votto …”

And then the signal and the voice disappeared – for good.