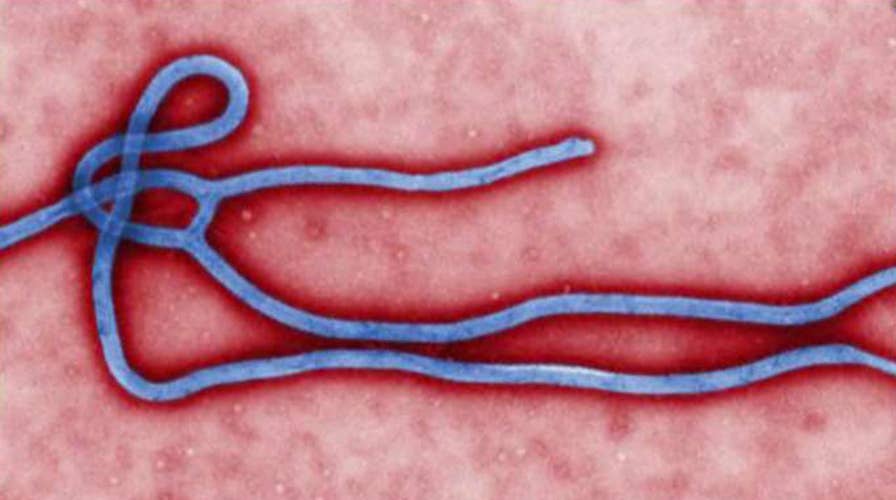

How ready are we if Ebola reaches the US?

Ebola deaths in the Congo exceed 1,000; Fox News medical correspondent Dr. Marc Siegel weighs in.

I’ve spent time in the field as a physician, and I think the health care workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo are among the bravest people on Earth right about now.

In addition to dealing with rebel attacks and community distrust, every time it’s announced that the DRC’s Ebola outbreak may be under control, it seems to spread with a new vengeance, setting sometimes daily records.

And Ebola has finally crossed the border into Uganda where authorities have identified over 100 people who may have come into contact with the disease, including health care workers.

EBOLA FEARS WORSEN AFTER MORE THAN 300,000 FLEE CONGO OVER VIOLENT ETHNIC CLASHES: REPORT

In 2014, the West Africa Ebola pandemic put the world on edge and took 11,000 lives. Health care workers did not have access to the fundamental tools of infection prevention and control, and it put their lives at significant risk.

Ebola deaths were 103-fold higher in health care workers in Sierra Leone than in the general population, 42-fold higher in Guinea health workers, and Liberia lost eight percent of its health workforce to the disease. Why? In part because health care workers didn’t have suitable hygiene resources and could not adequately wash their hands.

Tragically, problems with water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) persist. This DRC outbreak is now the second-longest in recorded history. Key barriers to curbing this complex outbreak include lack of triage and isolation facilities, lack of protective equipment, the inability to decontaminate, and inadequate waste management.

In other words, there’s still a real problem with access to the foundations of global health: WASH in health care facilities.

In the DRC, 49 percent of health care facilities have no water services and 59 percent have no sanitation services. A new report from the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF sets a first-ever global baseline measure of the availability of WASH inside health care facilities based on data from 125 countries.

The findings are dire: 2 billion people are served by health care facilities without basic water services while 1.5 billion people are served by health care facilities without sanitation.

Preventing and containing disease outbreaks – and delivering adequate health care – is impossible with no clean water, no soap and no toilets.

These circumstances present a global threat of their own. Bafflingly, WASH is an area where global health policy continues to dangerously lag.

While there is no doubt that the DRC’s Ebola outbreak has grown increasingly complex, the global health community must focus attention on not just the immediate problem, but the foundational weaknesses that cripple the prevention and containment of a range of potential pandemic diseases, like MERS, Nipah virus, Lassa hemorrhagic fever, Rift Valley fever and Zika, as well as Ebola and antibiotic resistance.

For these viruses as well as a host of more common infections, improved hygiene is the most powerful and cost-effective way to prevent and contain illnesses, protect vulnerable newborns and the immune-suppressed, prevent person-to-person transmission, avoid antibiotic resistance, and stop global pandemics.

Getting WASH into health care facilities is a solvable problem. When I served as U.S. Senate majority leader, I drafted legislation to formalize U.S. policy addressing the overall lack of safe water and sanitation in developing nations.

Alongside Democratic leader Sen. Harry Reid of Nevada, we passed the “Senator Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act” (named for our colleague and longtime champion for WASH) in 2005 with strong bipartisan backing. For the first time, WASH became an objective of U.S. foreign assistance.

American commitment alone cannot be the answer, of course, but a budding global public-private collaborative effort to get WASH into health care facilities is emerging.

In the U.S., 80 private donors and non-governmental organizations just announced commitments to new funding, technical assistance, research and evaluation, maintenance training and advocacy totaling well over $120 million.

In September, a global event on WASH in health care facilities will take place in Zambia, organized by WHO and UNICEF, to focus on country action and global work plans.

And recently, the 194 WHO member states (including the U.S.) passed a significant World Health Assembly Resolution, marking the first time countries have joined together to acknowledge this global health crisis and begin the next steps.

Now is the time to make real our words and move this global resolution forward with concrete plans and action. From health security to economic security, it’s in our nation’s best interest to elevate this issue and augment these efforts. And it is the right thing to do. So let’s take these logical next steps.

The U.S. Agency for International Development must continue to elevate the fundamental importance of WASH in its overall work (in accordance with the 2017 Global Water Strategy) and adopt an agency-wide policy that WASH be made available in every health care facility in which the agency is active. This will require coordination between the water and global health teams.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must ensure that WASH in health care facilities is integrated into its existing programs related to pandemic disease preparation, prevention and control.

Which brings us back to the DRC. This is the ninth Ebola outbreak in the DRC since 1976. So far, nearly 2,400 people have been infected – including 126 health care workers – and more than 1,600 people have died. The outbreak threatens neighboring Burundi, Rwanda and South Sudan, and has entered Uganda. This outbreak should be a harsh reminder that pandemics know no borders and investing in prevention is the best cure.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE BY BILL FRIST