(Copyright 2016 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.)

Outside, protesters screamed “Stop protecting rapists!” Not the usual scene at a speech by the Secretary of Education.

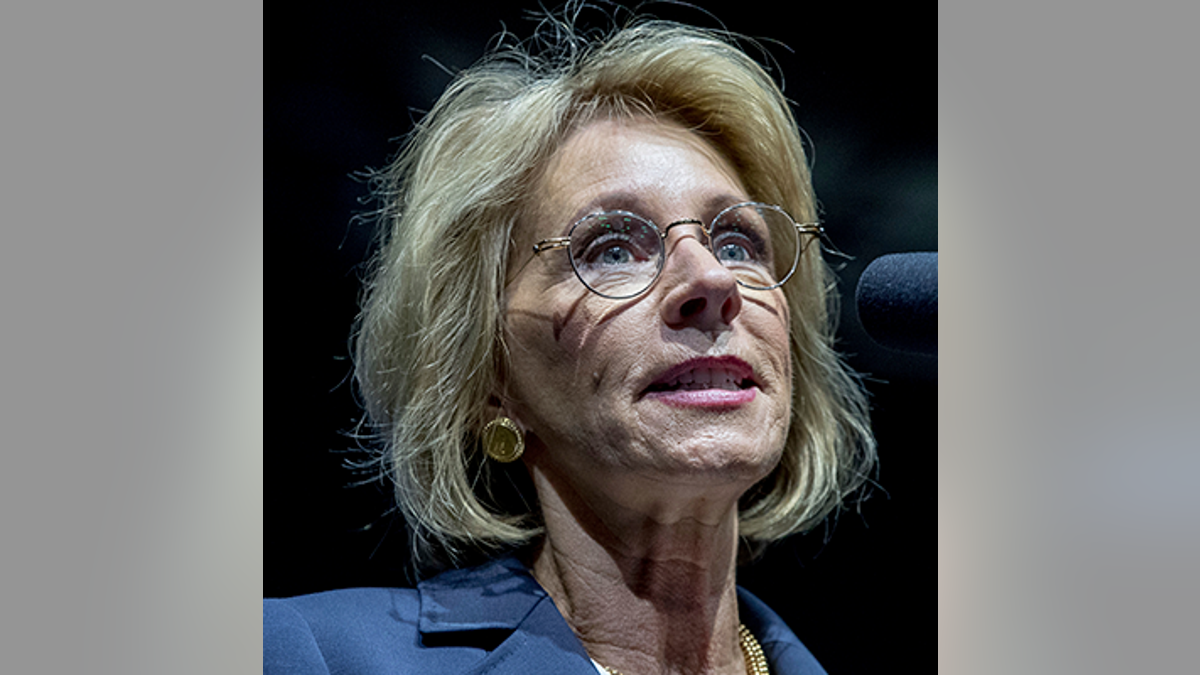

But Betsy DeVos isn’t just any Education Secretary. And her speech on Thursday at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School wasn’t just any speech.

Because DeVos was saying President Obama got it wrong, and it’s time to change how sexual assault is dealt with on campus. “Instead of working with schools” as she put it, “the prior administration weaponized the Office for Civil Rights.”

Critics claim she’ll be turning her back on rape victims if she overturns the system now in place. But in reality, what she’d be doing is setting it right.

On April 4, 2011, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights sent a “Dear Colleague” letter to campuses setting up new requirements for sexual assault policy. From now on, the standard of evidence for campus tribunals would be the lowest possible—a “preponderance of the evidence.”

This was a unilateral move on the part of the Obama administration, not backed by any legislation recently passed by Congress, but based on their new interpretation of decades-old Title IX, which forbids sexual discrimination in education.

The Dear Colleague letter was a “significant guidance document,” and did not have the force of law. But it couldn’t be ignored—any college that defied the administration could find its funding cut.

What followed, under the Department of Education guidelines, was a lack of due process norms that are the foundation of our legal system.

At various campuses, the accused were not allowed legal representation, had no right to see the evidence against them, had no right to introduce certain exculpatory evidence, had no power to cross-examine witnesses, had no protection against self-incrimination.

And all the while these cases were often being tried by people with little expertise in the area, though some were activists with strong political views on the matter. Sexual crimes are tricky enough for the regular court system to handle—colleges seemed overwhelmed with the task.

Many of the accused were found responsible—though they didn’t feel they got a fair chance to defend themselves—and were expelled, a black mark against them in any future endeavor. Numerous students accused of sexual assault have sued their colleges. Schools have paid out millions in settlements, and in some cases were forced to reinstate expelled students.

It’s results like these that helped convince DeVos of the need for change. But that didn’t stop those who defend the present regime from claiming DeVos is on the side of rape deniers.

However, the Secretary of Education is simply trying to establish a proper balance. In recent months, she’s met with both victims of assault, and with the wrongly accused, stating “All their stories are important.”

And in her speech, she made it clear both sides must be listened to. “Every survivor of sexual misconduct must be taken seriously. Every student accused of sexual misconduct must know that guilt is not predetermined. These are non-negotiable principles.”

There’s no simple way to deal with the complex issue of sexual assault on campus, but any solution should look at the problem honestly and impartially, without putting a thumb on the scales of justice. Reform will be tricky, but the speech DeVos just gave is a good first step.