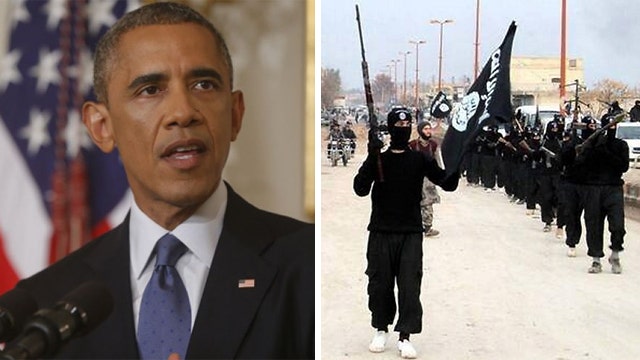

“Do you have a strategy now, Mr. President?” asked the cover of the Daily News next to a photo of the second American journalist to be beheaded by the terrorist group ISIS.

The impulse to “do something” to counter such evil is strong.

But why do we assume that government doing something is always an improvement over government doing nothing?

[pullquote]

In domestic policy, encouraging government to act leads to nonsense like the “stimulus spending” that created boondoggles such as Cash for Clunkers.

Our foreign policy record isn’t much better, despite big successes such as stopping Hitler. Consider the unintended consequences of involving ourselves in other conflicts, such as Vietnam.

President Carter, now derided as a weakling, wasn’t about to sit around and “do nothing” when Russians invaded Afghanistan. Carter armed Islamic fighters, the mujahidin. Bold move.

But later those fighters formed the Taliban.

President Clinton lobbed missiles at Al Qaeda without doing much damage. Usama bin Laden mocked the U.S. as a “paper tiger” for such ineffectual tactics.

When President George W. Bush chose to go to war with Saddam Hussein, Vice President Cheney assured the world we’d be hailed as “liberators.” After we weren’t, hawks said the invasion still made the world safer, because Saddam harbored terrorists.

Well, Iraq is definitely a harbor for terrorists now.

Despite our frequent military interventions from Southeast Asia to Latin America, in the Wall Street Journal, Brookings Institution foreign policy analyst Robert Kagan warns about “America’s dangerous aversion to conflict.”

Aversion to conflict?

I too get frustrated watching evildoers abuse Americans overseas. Maybe the plan to “train and equip” certain tribes and eventually “destroy ISIS” that President Obama will speak about tonight will be a good thing.

But I’m skeptical.

After the toppling of Saddam, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice thought it was smart to support Sunni militants who wanted to fight al-Qaida. But now it’s Sunni militants who lead ISIS.

Secretary of State Hilary Clinton thought it was smart to aid Islamist militias in Syria and Libya. In Libya, “A monstrous little dictator was removed,” writes Peggy Noonan in the Wall Street Journal, but that “left an opening for people who were more monstrous still, who murdered our ambassador, burned our consulate in Benghazi and have now run us out of Tripoli.”

We may soon do an about-face and help Bashir Assad against militias we had hoped would overthrow him (a few months ago, when he was the latest in a long line of foreign leaders who hawks likened to Hitler).

We don’t know what our interventions will bring. If we remove ISIS, we remove the biggest threat to terrorist cells like Hamas. Fighting these groups is like fighting Hydra, the monster from Greek mythology. Cut off one head, two more grow back.

The policy twists and turns come so fast that Americans may give up on following them all. I don’t blame them: In Syria alone, there’s conflict between Assad’s government, the Free Syrian army, l-Qaida, Jabhat al-Nusra, the Islamic Front, Hezbollah, ISIS and so on.

Remember hawkish Sen. John McCain appearing in a photo with some Syrian fighters who turned out to be terrorists? It’s hard to keep track.

One of the terrorists’ goals is to get us to overreact. They understand how much it costs us. In a piece titled “The Beheadings Are Bait,” Matthew Hoh from the Center for International Policy reminds readers that Usama bin Laden said, “All that we have to do is to send two mujahidin to the furthest point east to raise a piece of cloth on which is written Al Qaeda, in order to make the generals race there and cause America to suffer human, economic and political losses.”

Maybe it’s time for America to stop taking the bait. Islamic militants do monstrous things all over the world. We cannot stop it all.

There may be actions we can take. Thousands of people in Iraq were rescued by airdrops of food and water. Air strikes stopped the ISIS advance.

But there is a big difference between that type of action and prolonged engagement.

The urge to “do something” is understandable. But government can’t get domestic policy right. Don’t assume it gets foreign policy right.