Start children off on the way they should go, and even when they are old they will not turn from it.

—Proverbs 22: 6

My mom called recently and in the course of our conversation she said, “My friends all tell me they wake up withyou every day. And I thought to myself,You wake up with my daughter? But then it hit me. They were talking about your news show.” And then she added, “Honey, I think you might be famous.” “I know, Mom. It’s so crazy.” We both laughed at the idea. My mom wasn’t the first to say something like this to me.

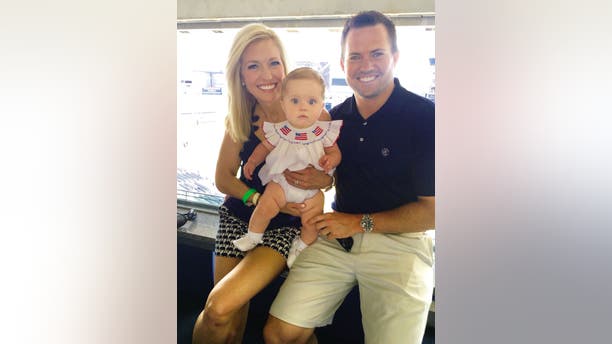

Not long after my daughter was born I was talking to a group of girlfriends about schools and I expressed my apprehension about getting Hayden into the right one. “Oh, you won’t have a problem,” one said. “You’re a daytime news anchor.”

“Yes, but I don’t feel that makes any difference,” I replied. They all tried to set me straight. “Ainsley, you have to see yourself the way others see you.”

I don’t think that’s right. I may have a very visible job that allows more than a million viewers to invite me and my fellow anchors into their homes every morning, but that doesn’t make me famous; nor does my job entitle me to any kind of special privileges.

When I think of the position that’s been entrusted to me, I feel a great weight of responsibility. Not a day goes by that I don’t look at myself in the mirror and ask God, “Why me? Why did you choose me, Ainsley Earhardt from Columbia, South Carolina, to be one of a handful of female national news anchors?” I don’t know the complete answer to this question except to say that God put me here for a reason and that reason has nothing to do with me becoming famous.

When I think of the position that’s been entrusted to me, I feel a great weight of responsibility. Not a day goes by that I don’t look at myself in the mirror and ask God, “Why me?"

Now, I have to admit that I didn’t always feel this way. When I was five years old I remember watching the opening of the Oscars with my mother and crying as I watched celebrities walk in on the red carpet. Why would any child cry watching the Oscars? For me, the reason was simple: I wanted to be there so badly that I burst into tears. I remember telling my mother that someday I was going to live in California and be a famous actress.

“California,” my mother replied, “life’s a beach there.” I had no idea what that meant.

Around the same time, my siblings and I were looked after by a wonderful lady named Miriam “Mimi” Grant until my mom got home from work.

Every day when she put us down for our naps, she turned on the television to watch her soap operas. I knew about soaps because my great-grandmother called them “the stories” and always told my mother they were sinful.

My great-grandmother’s warning didn’t stop me from sneaking out of my bed and tiptoeing into the den behind our babysitter where she couldn’t see me and watching them.

The actors were all beautiful and seemed to have perfect lives. The entire idea of being in front of the camera seemed so romantic. Deep down I just knew that that would be me someday, either in front of a camera or on the stage. My parents indulged my fantasies, to a point. I attended theater camps and classes growing up, but there was never any talk of me making a life out of acting. My parents were much too practical and grounded for that.

I actually got my chance to be in the movies while I was still in middle school. Twice. The first time occurred when Disney came to South Carolina to shoot a movie set in the 1930s called "Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken."

I may have a very visible job that allows more than a million viewers to invite me and my fellow anchors into their homes every morning, but that doesn’t make me famous; nor does my job entitle me to any kind of special privileges.

As soon as I heard they needed extras I was determined to land a part. I went to the auditions and was selected to be one of the kids in the crowd when the female star’s love interest, Michael Schoeffling, was getting into an argument with a group of men at the local fair. Years before, he had been the actor in "Sixteen Candles" who kissed Molly Ringwald at the end of the movie and was just so handsome to me at the time.

Actually being chosen to be a child in the crowd made my little middle school heart race. I just knew that this was going to be my big break and one of the directors was going to notice me. And they did. They needed a girl for a larger part than just a face in the crowd, and this role would actually get a line or two. One of the directors pulled me out of the crowd of extras along with another girl. I was thrilled—this was my chance. But then I gave them a big smile and they saw the braces on my teeth.

“She can’t do it,” they said. “Braces don’t fit the time period.”

I was heartbroken. Instead of a speaking part I ended up in the background wearing a red dress and eating cotton candy.

My second time came in a movie about college football called "The Program." This one starred Halle Berry and James Caan. The movie auditions and information made the local news because it was filmed in my hometown and scenes were shot at the Univer- sity of South Carolina’s Williams-Brice Stadium.

Watching my mom taught me that hard work, not dreams of grandeur, is the key to success in life.

Since this movie was set in the present, my braces weren’t a problem. I went to the auditions with a head full of dreams. However, once again, I was just a face in the crowd in a background filled with extras.

My middle school girl visions of fame did not come true, but they also did not die—and thankfully my mom and dad knew just the right approach to raising a daughter with dreams of grandeur. My mom used to tease me, saying she hoped I married a rich man someday because I was such a dreamer with champagne taste.

She didn’t mean that the way it sounds. It was her way of telling me to get my head out of the clouds. Dreams don’t come true by waiting for Prince Charming to arrive. If my dreams were going to come true it was going to be because of my own hard work.

My mother showed me the power of hard work and determi- nation. She taught early childhood development, but she was no ordinary teacher. I watched my mother go through the very rigor- ous process of becoming a national board-certified teacher.

Only 3 percent of all teachers across America are nationally board certified. The process is so demanding that only 40 percent of those who attempt it make it through the first year. But my mom completed the program while working full-time, raising three kids, and running our household. Watching her taught me that hard work, not dreams of grandeur, is the key to success in life.

My father taught me confidence, which allowed me to follow my dreams and never be afraid of rejection.

When I was a little girl my dad coached basketball at Wofford College in Spartanburg, South Carolina. He also had big goals of moving up the coaching ladder from Wofford and becoming the head coach of a major college program.

My father taught me confidence, which allowed me to follow my dreams and never be afraid of rejection.

His real dream job was at his alma mater, the University of South Carolina. However, one year after my little brother was born my dad left coaching and took a job selling janitorial and industrial supplies.

We movedfrom Spartanburg to Charlotte, North Carolina. I completed my third grade year at Sharon Elementary School (which I would later learn was the same school two other Fox News anchors attended), but after that school year, my father’s company had an open position in his hometown of Columbia, South Carolina. We all missed South Carolina and were delighted to pack up and move again. Instantly, my father was successful. He proved himself to be one of the top salespeople in his company. It wasn’t just that he was a good salesman—he worked incredibly hard and was very well-liked. I can still see him sitting up late at night writing out thank-you notes to all the customers he saw that day.

As my older sister, Elise, my brother, Trent, and I got older and closer to college age, my dad worked side jobs. Sometimes that meant cleaning floors for businesses at night or delivering the loads of toilet paper a company needed for the following morning.

He was also in the Army Reserves. He served at Fort Jackson one weekend every month and two weeks every summer. He sacrificed a lot for our family and hard work was celebrated and expected in our home. He did all of this because he had a second dream, the dream of putting all three of his children through college.

Growing up, I never saw Dad use a credit card, he paid with cash and I remember him telling me he made double payments toward the mortgage every month until it was paid off. He believed in working hard now so you can enjoy the fruits of your labor later.

The value of hard work was only one small lesson my parents taught me. For the first few years of my life, we lived in a one-story, L-shaped house in Spartanburg with a huge backyard with many colorful azalea bushes and honeysuckles, a gorgeous dogwood tree in the front yard, and a massive magnolia tree which separated us from our neighbors.

Elise moved into my bedroom with me when our brother was born. I was five and a half when he came along, and I was very excited about having a baby to love. Elise and I fought over who got to feed him, change his diapers, and take care of him. On his wedding day we joked that he’d been raised with three moms. Poor guy. We couldn’t help ourselves. Having a baby brother was like having a real, live baby doll.

Because of her teaching job, my mom always left the house early, which left my dad to get us up and ready for school. He’d come into our room and wake us up by opening the shutters and sometimes tickling us.

There was no sleeping in at the Earhardt house, not even on the weekends. Saturday mornings he came in early, threw open the shutters, nd said, “Rise and shine. It’s time to get up. If I’m up, you’re up!” We’d drag ourselves out of bed and go downstairs for breakfast.

Most mornings I found a little note next to my cereal bowl in which my dad had written out a quote or a Bible verse or a poem he’d found. Since he was a great coach, I imagine these were the same kinds of sayings he used to motivate his players.

They motivated me. I still have a lot of them today. One of my favorites was, according to my dad, uttered by Walt Disney. It read, “I hope I’ll never be afraid to fail.” That’s how my dad taught me to approach life.

I also loved the one that said, “Attitude determines aptitude,” and another that said, “Stay up with the owls—don’t expect to soar with the eagles.” When I got a little older he gave me one that said, “Nothing good happens after midnight.”

I loved these notes. I did not, however, love his habit of making us drink a glass of unsweetened grapefruit juice every morning. My sister and brother and I held our noses as we forced it down. Apparently my dad had read somewhere that grapefruit juice helped prevent sickness.

After breakfast we piled into the car for the car pool to school. My favorite days were those when my dad brought home the team van from the college where he coached.

Elise and I would cheer when he would drive it home the night before and we saw it parked in front of our house or in the driveway.

On car-pool days one of us always hid behind the backseat while my dad picked up the other kids. They climbed in the van and asked, “Where’s Elise?” or “Where’s Ainsley?” We said something like “Oh, she stayed home sick today,” which of course never happened because of all the grapefruit juice we drank.

Then, once everyone was in the van, whoever was hiding in the back jumped out and yelled, “SURPRISE!” Elise and I thought that was great. The joke never got old.

Whether we were in the van or not, my dad always made the drive to school interesting. Every day we drove past a big tree with a hole in the middle of it. My dad told us a bear lived in the hole. He even had a name for the bear. Another house on our route had a large clubhouse in the backyard that looked like a dollhouse. Whenever we passed by it my dad said, “You know, the Smurfs live in that dollhouse. I wonder if they’re awake. Let’s honk the horn and wake ’em up.” We always laughed.

Mom was still at work when we got home from school. Mimi took care of us when we were very young in Spartanburg, South Carolina, but when we moved to Columbia, I was in fourth grade and Elise was in seventh. By that point, we were old enough to come home to an empty house, make a snack, and watch TV until Mom came home.

Elise and I would watch a soap opera called "Santa Barbara," which is no longer on the air, but when we heard Mom opening the garage door, we had to quickly turn off the TV, since we still were not allowed to watch soaps.

We’d run upstairs to our bedrooms and start working on our homework. My brother was usually outside playing with all the boys in the neighborhood.

Mom started dinner along with doing everything else that had to be done to keep the household running. My sister, brother, and I did our part. All of us had daily chores. Now that I am a mother I have a newfound respect for my mom. Honestly, I don’t know how she did it. I find it is hard enough to be a working mom with only one child . . . somehow she did it with three.

Growing up, we talked about God in our home and said a blessing at every meal and prayers before bed.

I definitely grew up in a Christian environment, but we didn’t read the Bible as a family every night or memorize Scripture. Instead my parents would find their own ways to remind me of God’s place in my life, which gave me a good perspective on life and the disappointments it brings.

When I was in eighth grade I tried out for the cheerleading squad. I thought it was going to be an easy audition because I had been on the squad the previous year and got along beautifully with the coach and other cheerleaders. However, when the list of girls who made the team was posted, my name was missing. I was crushed. Six of the current cheerleaders in seventh grade didn’t make the team for the next year. We were all in tears and being consoled by our coach who was also emotional. She cried with us. When I got home and shared the news with my parents, my dad said something I have never forgotten. “You got to be a cheer- leader last year, right?” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“Another girl probably needed that spot this year more than you. Ainsley, God knew you could handle the rejection of not mak- ing the squad. He made you a confident, positive person. You will be fine. He will bless you in other ways, just wait and see,” he said. Those words have stuck with me the rest of my life. My dad taught me to look at life’s setbacks through eyes of faith.

We attended church every Sunday. Church on Sundays was a must—even if we spent the night with a friend. We either went with the friend or Mom and Dad picked us up early from the friend’s house and we went to our own church as a family.

When we lived in Spartanburg and Charlotte, we attended very formal Episcopal churches. They were beautiful, with stained-glass windows, long aisles, and sanctuaries shaped like a cross that are traditional for Episcopal churches.

When we moved to Columbia, my father felt very strongly about joining Ebenezer Lutheran Church. That was the church he grew up in and generations of our Earhardt rela-tives had attended services there. It was a relatively long drive for us, about fifteen or twenty minutes, but Dad felt God calling him back to his childhood church.

The members of the congregation were older and there weren’t a lot of young families. Dad knew God wanted him to help grow the church and bring new life into an older congregation, so the whole family got involved.

My dad served on the church council and my mom was part of the altar guild. In high school I represented the youth group on the church council and became youth-group president. This was also the church where I was confirmed.

Church was a big part of my life growing up, but something still seemed to be missing. Every year our church youth group at- tended Lutheran Christian camps as well as taking ski trips and other activities. I was confirmed and very active, but I still felt like something was missing. This wasn’t enough. I remember one day riding to high school with one of my best friends, Cindy, and asking her a question that was heavy on my heart.

“Cindy, how do you know you’re going to heaven?” I asked. “Well, if you are a good person, you will go to heaven,” she said. “I feel like I am a good person and I try to be nice to everyone, but I don’t know if that’s going to get me to heaven,” I replied.

Deep down I knew that it wasn’t enough. I wanted to be certain. Then I reminded myself that I was not worthy of heaven and, of course, I never expected God to think I was good enough. I remember thinking I was only allowed a few prayers; God would think I was selfish if I had too many requests.

I knew He was busy answering prayers all over the world, so I told myself I could only talk to God when the prayer was selfless or really important. I thought of it as “saving my favors for when I really needed a prayer answered.” Therefore, I decided to try my hardest to get to heaven and hope for the best when I came face-to-face with Him at the Pearly Gates.

Going to church and trying to be a good person didn’t keep me from doing things that deep down I knew I shouldn’t do. Myfriends and I always wanted to be in the middle of the fun, so when we heard about a party, we were there.

Through high school and my first two years of college I did things that were considered normal for people my age. For instance, most of my friends were smokers. At that time students were allowed to smoke at my high school. We were born in the seventies and most high schoolers took part. In fact, we even had a designated smoking area at school called “The Back Porch.”

Occasionally I walked out and took a few drags of a friend’s cigarette. Smoking was a social event for me. It was just something most people did. We all hid it from our parents, but truth be told, many of them smoked, too, so we picked up the habit. We knew it was not healthy, but all my friends just assumed we could smoke through high school and college, hide it from our parents, and then quit when we got married one day.

It was pretty naive, especially considering I’d witnessed first- hand how hard it was to quit the nicotine habit. My mother smoked when I was little. My dad, sister, and I HATED it. My mother’s parents, my Mimi and Pop, smoked. They smoked inside their house and in their cars. The smell was awful. Still, to this day, when I get in the car of a smoker, it takes me back to my childhood and makes my stomach turn. But Mimi, Pop, Mom, and her sister, Lynn, all gave up the habit together when Pop was diagnosed with a lung disease. It was not easy for Mom. She quit for ten years, but started smoking again later and tried hiding it from all of us. Dad has never smoked. He is our practical thinker. So Mom hid her smoking from him. We all did. If he had known I was a smoker, he would have been extremely disappointed.

One time he discovered a pack of my cigarettes on the front walkway outside, and I later found them on my pillowcase. That was his way of saying, “I don’t want a confrontation or hear you try to lie your way out of it, but I want you to know how deeply disappointed I am.” That hurt. I knew I had let him down.

When I started smoking more and more throughout high school, I decided if I was going to pick up this nasty habit, I was going to do it in the most glamorous way. After all, my friends already called me “Hollywood.” So I bought a silver cigarette case and filled it with my cigarette of choice: the skinny, minty Virginia Slim Super Slim menthol. We shortened the name to the “VSSS.” When my friends wanted one, they said, “Hollywood, may I have one of your VSSS’s?” I smiled and handed them my cigarette case—enjoying every minute of it.

I didn’t think anything I did was that inconsistent with at- tending church on Sundays. The Lutheran Church didn’t cast condemnation or make me feel guilty. I knew my parents and God wouldn’t approve of my choices, but I was still able to separate my social and church lives. It was as though those two parts of my life stayed in their own spheres.

As I got older and was able to go out at night (my curfew was 11 p.m.), we all lied to our parents, went to parties on Saturday nights, and then showed up bright and early for church on Sunday mornings. That didn’t seem like a big deal. Everyone else did the same thing. In fact, most of the time I felt pretty good about my life. I had a Bible, actually several. My dad gave them to me. I kept one of them next to my bed, and I read Scripture when I was sad or going through a tough time. My best friend Cindy, who drove me to school, gave me a bookmark with Scripture verses that correlated to particular emotions.

And yet, when I was around people who were really “sold out” for Jesus, I knew something was missing in my life. One guy, Eric, in particular really made an impression on me. He hung out with the most popular people and was quite outspoken about his faith. He was older than I was and had a long-term relationship with a girl in Atlanta. He told everybody they were committed to wait un- til marriage before having sex. That made an impression on me. I wanted to be that kind of person as well. Around the same time, our youth group leader played a Christian video for us talking about sex and the struggles high school students experience.

One girl in the video said, “I am still a virgin, and any day I can be like my friends, but they can never go back and be like me.”

Although I know now God is all about redemption and grace, I still wanted my virginity to be a special gift I gave my husband on our wedding night. That was important to me.

Eric was the closest thing on earth to Jesus for me. Somehow he was able to live a solid, Christian life, make good choices, and sur- round himself with the smokers and drinkers. As John 17:16 sug- gests, he was in the world but not of the world. I wanted to be like that. So, when he hosted Young Life, a campus ministry geared toward high school students, at his parents’ house—I was there. There was always pizza, good snacks, Coca-Colas, and a good mix of the social crowd and Christian crowd. I always wanted to go and never wanted to leave.

We all congregated in Eric’s basement and sat on the carpet in front of a movie screen that displayed the words of contemporary Christian songs. One leader played the guitar and another sang. After we sang a mix of secular and Christian songs, one of the Young Life leaders told his or her story or gave a Bible lesson. One college leader, who was cute and seemed cool (all of the high school girls loved him), shared his story about Jesus saving him from a life of alcohol and drugs. Although I had no desire to do drugs, I was still taken aback. This guy’s story seemed much more dramatic than just going to confirmation classes.

I also had someone in my life, even to this day I have no idea who, that put letters in my mailbox at random times. When the first one arrived I opened it and read, “This is Jesus. I just wanted to tell you that I love you.” Another said, “I watched you go through your day today. You were so busy but you never made time for me. Love, Jesus.”

I still have many of those letters today.

In spite of the letters, and the testimonies at Young Life, the only dramatic decision I made about my life during high school was to go to college.

I knew something was missing in my life, but I also had a strong sense that God had something in store for me that was bigger than high school, my hometown, and even South Carolina.

I didn’t crave fame, like I had when I was a little girl, but I was still in love with the idea of becoming an actress. As high school drew to a close I really wanted to attend a college with a great theater program, but I knew my parents would never go for it. My dad wasn’t working multiple jobs for me to major in something that had such an uncertain future. Whatever I did, I wanted to repay my parents’ efforts by working hard, to give back to them for all they’d done for me.

Excerpted from "THE LIGHT WITHIN ME," Copyright © 2018 by Ainsley Earhardt. Reprinted here with permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers