Can a NFL player be bullied?

League investigating threats against Miami Dolphins player by teammate

History reminds us that through the portal of individual injustice and abuse strangely flows the opportunity to let freedom ring. The NFL, with its reputation for no-nonsense reform on the battlefield, finds itself on the eve of such a hallowed moment taking place on America’s much larger battlefield for the health and well-being of our children: The fight against systematic abuse we euphemistically call bullying.

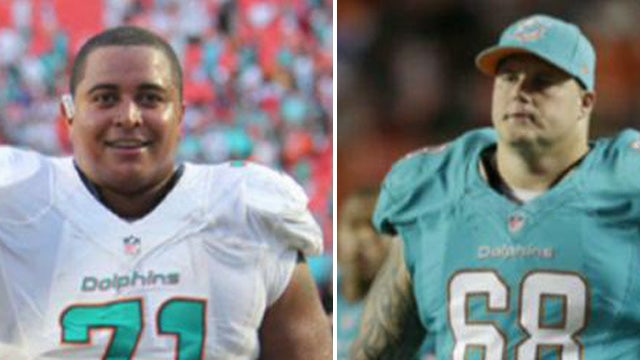

Enter the NFL’s reluctant, if not accidental, Rosa Parks: Dolphin’s offensive tackle Jonathan Martin.

Weary Rosa Parks, that icon of the Civil Rights Movement who refused to relinquish her seat on that segregated bus so many years ago, became a then-reluctant reformer against systematic abuse and humiliation.

Unlike Parks though, Martin, a Stanford graduate, left his seat and the Dolphins, reportedly after two years of abuse and assault, culminating in a move straight out of the bully playbook: When the target [Martin] sits down to eat at the team’s lunch table, the rest of us will get up in a public display of contempt intended to isolate and humiliate him. Reports say Martin stormed out and didn’t return.

His alleged ringleader bully could not have a more perfect name, since bullies are adept at walking socially inappropriate and criminal lines: Richie Incognito.

Respected coach Tony Dungy reportedly put him on his “DNDC" list: “Do Not Hire Because of Character.” Incognito, a 9-year-pro, was considered one of the NFL’s dirtiest players when he was with the St. Louis Rams. He may well be the NFL’s Bull Connor, too.

Reports say Incognito is considered a “leader,” within the team [Bull Connor was a leader, a Commissioner of Public Safety]. This also fits the bully profile since many are leaders – in the wrong direction.

Incognito reportedly sent texts and left voicemail messages for his biracial teammate that were racially charged [“half-n*****], threatened to defecate in Martin’s mouth, and track down his family and harm them.

This isn’t good-natured teasing where both people are laughing and where people come together in a spirit of fraternity. It is taunting, harassment and illegal, if proven.

By leaving the organization, Martin, a two-year starting player, forced it to contend with an age-old problem within sports, especially football, a program that we get more complaints about than all other high school sports programs combined.

Like Parks, Martin may well be a reluctant reformer who has shown America’s youth that to be a target doesn’t make you “weak” [starting tackle] or “stupid” [Stanford graduate]. By leaving a bullying hot spot, he shows us that such behavior makes us wise, brave and dignified.

Will the NFL show us similar virtue and lead us against what many believe is the leading form of child abuse in the nation, the only kind the most beleaguered among us are told to “just ignore”?

Because in the end, sports aren’t about sports. They are a fusing of our hopes and aspirations, our dreams and apprehensions. In their most noble expression, sports are the inner us, our collective need as incurably social beings to cheer for a common hero, an extension of our own heroic capacity, latent as it may be. We need help getting it out. Sports helps this happen.

Ironic, isn’t it, how the sport most hampered by accusations of abuse and psychological assault is also strangely the sport that can lead us as a nation to a freer, bullying-less future?

We know this to be true given its cultural horsepower. We feel it is so when we witness such adulation and athletic prowess. But will this governing body have the courage and guts to make it so through bold freedom-from-bullying initiatives that break past prejudice, ignorance, contempt and other building blocks of systematic abuse and injustice that bullying requires to exist and thrive?

That’s the real story here, and it’s the real victory an entire nation longs to celebrate and cheer.