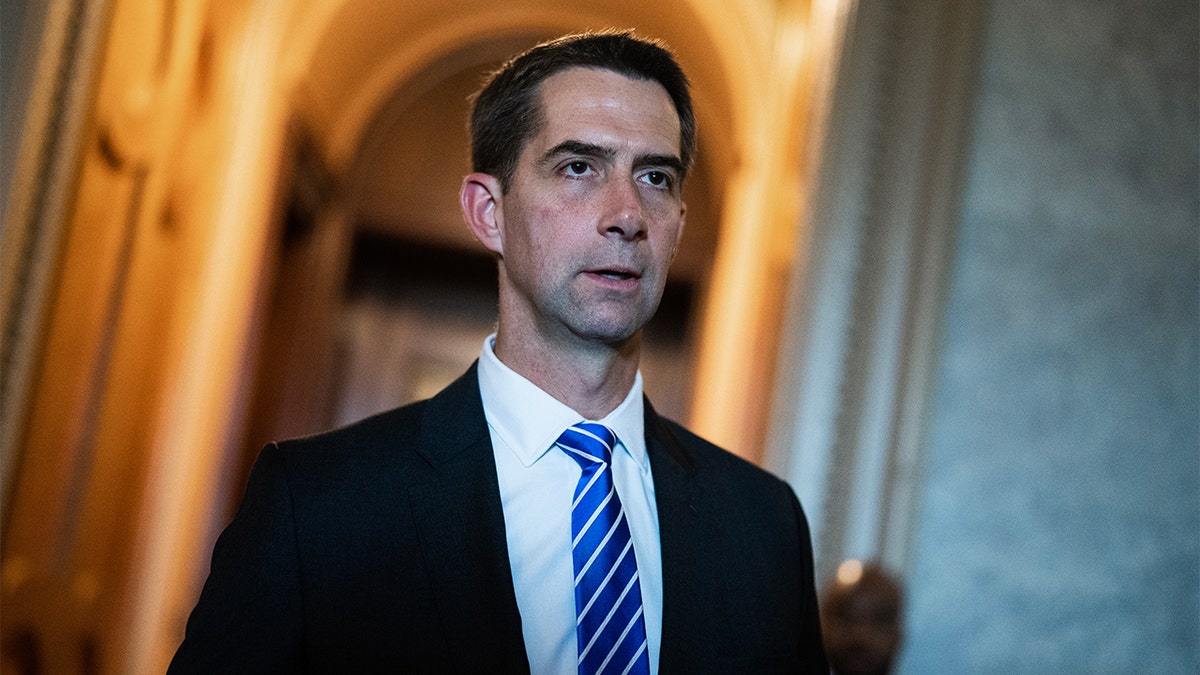

Tom Cotton makes case to give Ukraine aid while protecting US border

Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., joined Americas Newsroom to discuss the latest on the congressional fight to secure funding for Americas allies and the southern border.

In a display of animosity between two storied publications, The New York Times has accused The Atlantic of refusing to correct an anecdote in a story last week that painted one of its diplomatic correspondents as biased against Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton. But The Atlantic doesn't appear to be budging as there's more to the story than meets the eye.

Former New York Times opinion staffer Adam Rubenstein wrote a lengthy tell-all in The Atlantic on Feb. 26 that shed further light on the notorious uproar in June 2020 at the Times, when he was the primary editor of an op-ed by Cotton that suggested deploying the military to quell urban riots stemming from the death of George Floyd.

Included in Rubenstein's revelations of some of the tumult over the op-ed was an internal email from diplomatic correspondent Edward Wong, who told colleagues he often wouldn't quote Cotton in his stories because they "often represent neither a widely held majority opinion nor a well-thought-out minority opinion."

Wong took to X to vent frustration with how Rubenstein quoted him in The Atlantic, claiming he was taken out of context, and the New York Times has since reached out to the publication to update the piece.

The New York Times said The Atlantic "has twice declined to correct the passage regarding Edward Wongs email" as Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., is at the center of Gray Lady drama once again. (Left: (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images), top right: Shelby Knowles/Bloomberg via Getty Images, bottom right: (Screenshot/Atlantic))

"The Atlantic has twice declined to correct the passage regarding Edward Wong's email," a New York Times spokesperson told Fox News Digital. However, The Atlantic has stood behind Rubenstein's report.

Rubenstein, formerly of the right-leaning Weekly Standard before joining the Times, attempted to illustrate the cultural divide that non-liberals face at the paper. Deep into his piece, Rubenstein wrote about Wong's message, which was written in June 2020 as Times staffers erupted internally and publicly over Cotton's argument and the opinion department's decision to publish it. Opinion editor James Bennet was forced to resign amid the backlash; Rubenstein exited by the end of the year.

"A diplomatic correspondent, Edward Wong, wrote in an email to colleagues that he typically chose not to quote Cotton in his own stories because his comments ‘often represent neither a widely held majority opinion nor a well-thought-out minority opinion,’" Rubenstein wrote.

"This message was revealing. A Times reporter saying that he avoids quoting a U.S. senator? What if the senator is saying something important? What sorts of minority opinions met this correspondent’s standards for being well thought-out? In any event, the opinion Cotton was expressing in his op-ed, whatever one thinks of it, had, according to polling cited in the essay, the support of more than half of American voters," Rubenstein continued. "It was not a minority opinion."

Wong then spoke out on social media, saying the passage is simply "wrong."

"The quote is from a paragraph in which I discussed only China policy. I named a GOP senator whom I think speaks with more substance on China than Cotton. Readers know I quote a wide range of knowledgeable analysis," Wong posted on X.

"I respect @TheAtlantic. It should issue a correction. No one asked me for comment, or I would've pointed out the false context," Wong wrote. "The irony is that Rubenstein twisted a line to fit his ideological point — the very act he criticizes. And all serious journalists scrutinize opinions."

Wong, the former Beijing bureau chief for the Times, posted several other messages combating Rubenstein’s claim.

"In the context of what I wrote to my colleague, the phrase Rubenstein very selectively quotes fails to be evidence of his point or to reveal anything. He suggests NYT reporters use an ideological litmus test to determine whom to quote. Nothing could be further from the truth," Wong wrote.

"In the email, I wrote right after that phrase that another senator who is a GOP hawk on China makes ‘much more substantial’ comments. @TheAtlantic editors know I wrote this. Every serious journalist — including those at The Atlantic — makes this kind of evaluation of sources," he added. "Serious journalists evaluate whether the person they are interviewing or quoting is speaking from a well of knowledge or whether they are making comments for the sake of grandstanding, flame-throwing or trolling. That’s the basis for journalistic judgment, not partisanship."

Wong also posted a link to Semafor, which included a longer paragraph from the 2020 email on Monday. According to a screenshot of the message reviewed by Fox News Digital, it was dated June 3, 2020, the same date Cotton's op-ed was published.

Wong wrote at the time, "I was just telling someone earlier today that I often choose not to quote Cotton in stories I write on China b/c his comments are done solely for the purpose of flame-throwing and don’t add anything constructive or add anything that makes you see things in a new light. They often represent neither a widely held majority opinion nor a well-thought-out minority opinion. By contrast, his Senate colleague [Marco] Rubio, another GOP hawk on China, makes comments on China that are often much more substantial and not purely trollish."

The Atlantic and Wong did not immediately respond to requests for comment. Rubenstein also did not comment.

The New York Times said The Atlantic "has twice declined to correct the passage regarding Edward Wongs email." (REUTERS/Shannon Stapleton/File Photo)

Rubenstein took to X to defend himself, responding to posts from journalist James Fallows.

"James, with respect, I did NOT write that Ed won't quote the GOP in his stories. I wrote that he said he often chooses not to quote Cotton and gave his rationale. That's what he wrote," Rubenstein wrote.

Fallows said that Rubenstein "cut" the part where Wong said he was talking about China, failed to include "the part where he said he quoted other GOP Sens instead," and pushed back on the notion that Wong's email raised rhetorical questions because he "deleted" the parts of the email that addressed those points.

Rubenstein responded, "1) This is an admission that I quoted him accurately. 2) I didn’t say he doesn’t quote other Republicans, just that he often chooses not to quote Cotton. 3) His message IS revealing. As is the subject line of the email: ‘Cotton op-ed on using troops in US’ Talk about context!"

Others have come to his defense, too. The Dispatch's John McCormack noted Cotton that year had raised the so-called "lab-leak theory" about the origins of COVID-19, which many media outlets disputed at the time as "fringe," including the New York Times.

"If you were a journalist writing in June 2020 that you won’t quote Cotton on China because his comments ‘represent neither a widely held majority opinion nor a well-thought-out minority opinion,' isn’t that a reference to Cotton’s raising the Wuhan lab-leak theory in February 2020? If so, it isn’t a defense to say you’re willing to quote Rubio," he wrote on X.

Wong was one of four Times reporters who wrote a story published on April 30, 2020, that cast strong doubt on the theory as the Trump administration pushed spy agencies to link the Chinese lab to the virus' outbreak.

"Might have benefited from some Cotton quotes!" McCormack wrote.

The Atlantic previously told Fox News Digital "the entire [Rubenstein] piece was fact-checked, as is our standard policy" when asked about Rubenstein’s viral story of being scolded by then-Times colleagues for saying he likes Chick-fil-A.

A 2020 op-ed authored by Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., who suggested the military should be deployed to quell riots following the death of George Floyd, sent the New York Times into a tizzy. (Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

Rubenstein, who resigned from the Times a few months after editing Cotton’s infamous op-ed, wrote that the Times has essentially failed to fulfill its goal of being "journalistic, rather than activist."

Cotton's office didn't respond to a request for comment.

Fox News Digital’s Hanna Panreck contributed to this report.