Adam Sandler meets his doppelganger on the red carpet

The actor's lookalike describes the encounter

If you've ever thought you have an identical twin out there that you’re unrelated to — guess what?

You may be related to your "doppelgänger."

People with very similar facial characteristics likely share genetic variants, according to a paper published on August 23, 2022, in the journal Cell Reports.

"Our study provides a rare insight into human likeness by showing that people with extreme lookalike faces share common genotypes, whereas they are discordant at the epigenome and microbiome levels," said senior author Manel Esteller, a researcher at the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain, in a press release.

MARYLAND MOM OF 4 KIDS, INCLUDING 10-MONTH-OLD, IS DESPERATE FOR BABY FORMULA

Esteller and his team were inspired to look more into the phenomenon as more people post online of having a virtual twin without being genetically related to them.

The researchers wanted to better understand if there is a genetic basis for random human beings sharing facial features.

Zach Braff and Dax Shepard have always been a popular celebrity doppelgänger duo. (REUTERS)

They recruited 32 pairs of look-alikes from François Brunelle, a Canadian artist who was inspired to work on a photography project titled "I’m not a look-alike!" after discovering his own look-alike Rowan Atkinson — who is an English actor.

The researchers used three different facial recognition algorithms.

The participants provided saliva for DNA tests as well as completed comprehensive questionnaires about their lifestyles.

The researchers used three different facial recognition algorithms to objectively measure of likeness for the pairs after obtaining their headshot pictures.

"This unique set of samples has allowed us to study how genomics, epigenomics and microbiomics can contribute to human resemblance," Esteller noted in the media release.

Sixteen of the lookalike pairs in the new study had similar scores to identical twins when analyzed by the same software. (iStock)

Sixteen of the lookalike pairs had similar scores to identical twins when analyzed by the same software.

The study compared the DNA of these 16 pairs to discover if their DNA was similar, finding that 9 of these 16 pairs "clustered together, based on 19,277 common single-nucleotide polymorphisms."

The study also found that other characteristics such as physical traits — for example, weight and height — as well as behavioral traits, such as smoking and education, also correlated in lookalike pairs.

But experiences influence our DNA and what genes are turned "on" and "off" — which is what scientists call epigenomes, according to The New York Times.

Scientist wearing protective gloves examines DNA samples. (iStock)

And the environment influences our microbiome, the mix of bacteria, fungi and viruses inside us, the outlet added.

The study found even though the participants had similar genomes, their epigenomes and microbiomes were different.

"Genomics clusters them together, and the rest sets them apart," the scientists noted in the media release.

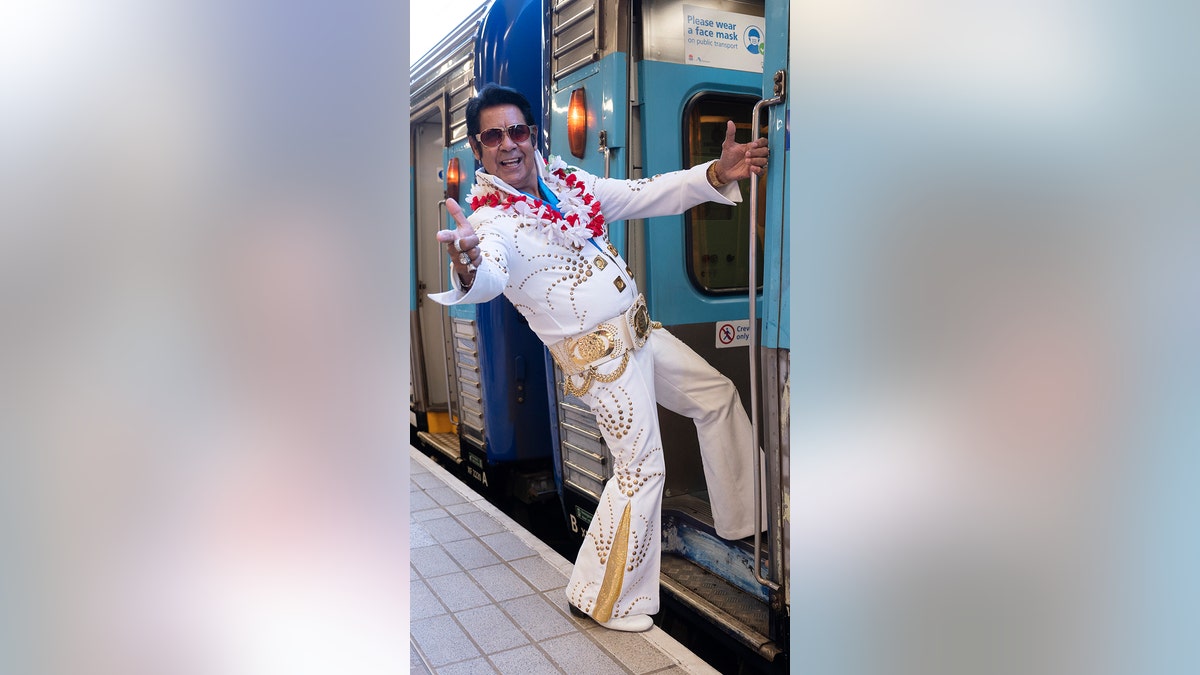

An Elvis impersonator boards the Elvis Express at Central Station on April 21, 2022 in Sydney, Australia. (Wendell Teodoro/Getty Images)

This suggests the pairs’ similar appearances are related more to their genetic makeup than compared to an environmental influence.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

The study noted overall that the research suggests "shared genetic variation not only relates to similar physical appearance, but may also influence common habits and behavior," per a press release.

"We provided a unique insight into the molecular characteristics that potentially influence the construction of the human face," Esteller said in the same release.

"These results will have future implications in forensic medicine."

"We suggest that these same determinants correlate with both physical and behavioral attributes that constitute human beings."

The study is limited by its small sample size and because it used 2D black-and-white images.

It’s also difficult to generalize the study because its participants were primarily of European descent.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

"These results will have future implications in forensic medicine, reconstructing the criminal's face from DNA — and in genetic diagnosis — the photo of the patient's face will already give you clues as to which genome he or she has," Esteller said.

"Through collaborative efforts, the ultimate challenge would be to predict the human face structure based on the individual's multiomics landscape."