Dr. Virginia Apgar has helped save millions of newborn lives with the method that bears her name

Influential physician and New Jersey native Dr. Virginia Apgar devised a system in the 1950s to assess the health of babies immediately after birth; the Apgar score has dramatically improved infant mortality rates worldwide.

Virginia Apgar kept score for America's babies and coveted scores on the violin as well.

She was a doctor, musician, instrument maker — and an overall pioneering female physician who overcame the prejudices of her era to forge a profound legacy for humanity.

Dr. Apgar is the namesake of a simple but powerful method of diagnosing the health of newborns one minute out of the womb.

The Apgar score, known well to doctors and anxious parents, is credited with helping to save the lives of millions of babies in the United States and around the world.

"She was a dynamic force and a leading woman in medicine who cut through problems like a hot knife through butter," Dr. John Truman, professor emeritus of pediatrics at Columbia University, told Fox News Digital in an interview.

"But she was liked by everyone, she had a great sense of humor and she loved music. Dr. Apgar was a formidable person."

American doctor Virginia Apgar (1909-1974), head of the Division of Congenital Malformations of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (March of Dimes), June 1959. Specializing in pediatrics, Apgar developed the first system of tests, known as the Apgar score, to assess the health of newborn babies. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Apgar attended Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City during the Great Depression, graduating fourth in a class of 90.

The top-tier student planned to become a surgeon.

She was told by surgery chair Dr. Alan Whipple that women were likely to fail in the profession.

"Dr. Apgar was a formidable person." — Dr. John Truman

She instead pursued the burgeoning field of anesthesiology, with a focus on obstetrics.

Dr. Apgar gained revenge on all those who doubted women in medicine through incredible success.

The Apgar score quickly became standard medical practice around the world. Infant mortality rates have improved dramatically in the years since, and Apgar’s method is one of the major reasons why.

A new mother is seen in her hospital bed shortly after delivery as she holds her newborn and studies his features. Since the 1950s, almost every newborn baby in the United States has been immediately diagnosed using the Apgar score devised by Dr. Virginia Apgar of New Jersey. (iStock)

"It’s outrageous today to think that women were told they couldn’t do surgery," said Fox News medical contributor Dr. Marc Siegel, a clinical professor of medicine and practicing internist at NYU Langone Medical Center.

"But she took the hand she was dealt and she soared to incredible heights," he said. "She became one of the first and most important anesthesiologists in the country."

A family that ‘never sat down’

Virginia Apgar was born in Westfield, New Jersey, on June 7, 1909, the youngest of Charles E. and Helen May Apgar’s three children.

Her father was an insurance executive who, like his daughter, enjoyed significant interests outside work.

‘PANDEMIC SKIP,' A COVID MENTAL HEALTH PHENOMENON, COULD DELAY MAJOR MILESTONES, EXPERTS SAY

Tinkering with radio earned Charles Apgar national notoriety as the "wireless wizard" and hero of the World War I homefront.

He uncovered a German spy ring by recording coded radio messages emanating from a New Jersey business on homemade equipment. His variable condenser is now kept by the Henry Ford Museum of Innovation in Dearborn, Michigan.

Dangerous enemy aliens corraled by Secret Service operatives at Gloucester, New Jersey, during World War I in 1918. Virginia Apgar's father, Charles, achieved recognition for uncovering a German spy ring in New Jersey during WWI with homemade radio equipment. (HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

The family "never sat down," Dr. Apgar later said.

Music was high among their interests.

"She took the hand she was dealt and she soared to incredible heights." — Dr. Marc Siegel about Virginia Apgar

"Virginia learned to play the violin as a child, and continued throughout her life," the National Library of Science writes of the celebrated doctor.

She graduated from Mount Holyoke College in 1929 and soon began knocking down doors for woman in medicine, in an era when leading authorities felt females couldn't perform surgery.

Apgar entered Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons on the eve of the Great Depression, one of only nine women in the class of 90.

Dr. Virginia Apgar (right) is shown in early 1962 with James P. Eakins. (Bill Peters/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

She blossomed professionally. Apgar became director of the new Division of Anesthesia at Presbyterian Hospital in 1938, the first woman to head a division at the hospital.

She became full professor of anesthesiology back at Columbia's College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1949, the first woman there to hold the title.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO UNLOCKED THE SCIENCE OF GENDER, NETTIE STEVENS, FEMALE RESEARCH PIONEER

"She was especially interested in the effects of maternal anesthesia on the newborn, and in lowering the neonatal mortality rates," the National Library of Medicine reports.

The scientist still found time to pursue her passion for the arts.

In addition to playing violin, Apgar was proud of her skills as a luthier, a stringed instrument maker.

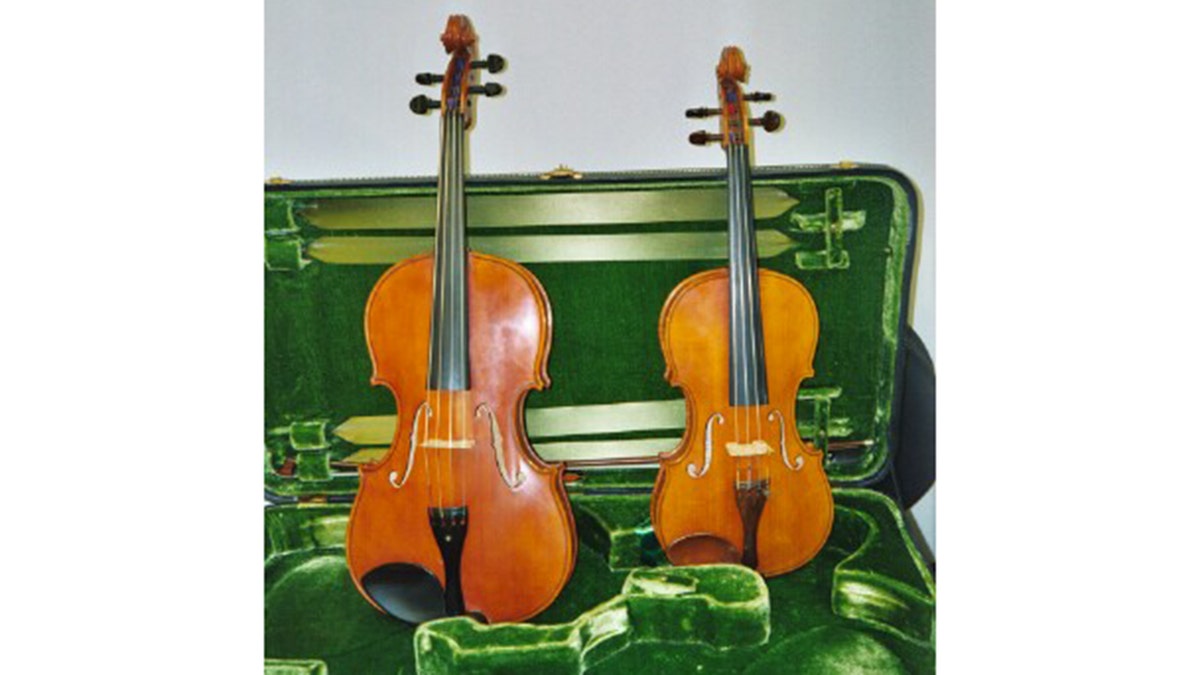

Dr. Virginia Apgar's viola and violin, both of which she made herself. With a second violin and a cello that she also made, she founded the Apgar String Quartet at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. Every year, incoming medical students perform with Apgar's instruments or faculty events, according to professor emeritus Dr. John Truman. (Courtesy Dr. John T. Truman)

Apgar once discovered that a telephone book box at her hospital was made of a rare Alaskan hardwood, according to a tale told by Dr. Truman.

"She thought, ‘Oh my God, this would make a fabulous viola,’" he said. She measured the box and had a friend make a cheap wood copy.

"Virginia learned to play the violin as a child, and continued throughout her life." — National Library of Science

"They crept through the hospital at 2 a.m., pulled out the Alaskan hardwood and replaced it with the replica."

Other sources say it was maplewood.

Regardless, the clandestine viola joined her collection of homemade instruments, with two violins and cello.

"That’s the making of a string quartet," said Truman. "And that’s the essence of music."

‘Traumatic shock’ of birth

The first minutes of human life are fraught with deadly peril, as Dr. Apgar was intimately aware.

A nurse caresses a newborn baby in an incubator while he sleeps peacefully (iStock)

She attended 17,000 births by the end of the 1950s. About 500 of those babies would have died in childbirth, based on government data from the era.

"Understand, birth is going from a place of fluid and nutrients, the comfort of feeding off the placenta, to a place where you have to breathe air and sustain yourself," said Dr. Siegel.

FOUNDER OF SAFE HAVEN BABY BOXES SHARES HER STORY AND HOPE FOR THE FUTURE: A ‘GOD-GIVEN PURPOSE’

"It is a huge, traumatic shock to a newborn. The transition causes tremendous stress."

Once outside, newborns face the immediate prospects of respiratory failure, cardiac failure and neurological issues.

Babies have died at an alarming rate throughout human history. Infant death remained a common reality in the first half of the 20th century, despite dramatic advancements in medicine.

Fox News medical contributor Dr. Marc Siegel told Fox News Digital that birth "is a huge, traumatic shock to a newborn. The transition causes tremendous stress." Dr. Virginia Apgar developed a scoring system to evaluate the health status of newborn babies — widely used to this day. (Fox News)

The infant mortality rate in 1950 was 31.9 deaths per 1,000 live births (3.2%), according to both the U.S. government and United Nations data.

"By 1952, Apgar had developed a scoring system to evaluate the health status of newborns, based on their heart rate, respiration, movement, irritability and color one minute after birth," writes the National Library of Medicine.

"The Apgar score is used everywhere and it's still used today."

Now done five minutes after birth as well, the Apgar score helps ensure that babies in crisis are given immediate care.

The most troubled babies are taken from the delivery room to the neonatal intensive care unit as quickly as possible, said Siegel.

Apgar’s methodology quickly spread across the United States and around the world.

The Apgar score helps ensure that any babies in crisis are given immediate medical attention. (iStock)

"The Apgar idea is universal, a way to determine immediately if babies are going to have problems or not," said Truman.

The Apgar score diagnoses babies on a scale of 1 to 10.

If a baby's Apgar score is 2 to 6, "you just better keep your wits about you because something is likely to go wrong," said Truman. "If it's down at 0 or 1, you instantly call all hands on deck."

‘MIRACLE TWINS’ ARE BORN TO ALABAMA WOMAN WITH DOUBLE UTERUS: ‘TRUE MEDICAL SURPRISE’

Dr. Siegel noted, "There's no question Apgar led to a pathway of accelerated care at the time of birth. The Apgar score is used everywhere and it's still used today."

‘Name is a lifeline for newborns’

Virginia Apgar died on Aug. 7, 1974, in New York City. She was 65 years old.

She was survived by a brother, Lawrence C. Apgar, and is interred in Fairview Cemetery in her hometown of Westfield, New Jersey.

Dr. Virginia Apgar created the Apgar score to diagnose babies immediately out of the womb, helping save the lives of millions of babies. She was honored with a U.S. Postal Service stamp in 1994. From the National Postal Museum collection. (© 1994 USPS. All rights reserved. )

Her work had a far-reaching impact on neonatal care worldwide.

The Apgar score, "along with her many other innovations," writes Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, "catalyzed the establishment of the subspecialties of perinatology and neonatology, the development of neonatal intensive care units, and the entire field of neonatal research."

The Apgar score "catalyzed … the development of neonatal intensive care units, and the entire field of neonatal research."

Apgar became an executive for the National Foundation March of Dimes in 1959, focusing on congenital defects.

She worked there until her death.

She wrote the book "Is My Baby All Right?" with Joan Beck in 1972, addressing the concerns of parents given her years of research and delivery-room experience.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

Dr. Apgar was celebrated by the nation with a U.S. Postal Service stamp in 1994. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1995.

Columbia's medical school still owns her string quartet instruments.

Playing them is a tradition and an honor for its musically inclined physicians of the future.

Dr. Virginia Apgar created the Apgar score, which is used by doctors to diagnose babies immediately after birth. On the right, a newborn baby boy is shown in Concord, Massachusetts. (Getty Images; Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Dr. Apgar's contribution to the welfare of newborns around the world is a legacy of almost unfathomable impact.

More than three of every 100 newborns in the United States died in 1950; only 1 of every 200 babies die at birth today.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

"The New York World Telegram and Sun once wrote, ‘Her name is a lifeline for newborns,'" the College of Physicians and Surgeons says in a tribute to one of its greatest alumna.

Dr. Apgar did "more to improve the health of mothers, babies, and unborn infants than anyone else in the 20th century."

"Surgeon General Julius Richmond once said," the college adds, "that Dr. Apgar had ‘done more to improve the health of mothers, babies and unborn infants than anyone else in the 20th century.’"

To read more stories in this unique "Meet the American Who…" series from Fox News Digital, click here.

For more Lifestyle articles, visit www.foxnews.com/lifestyle.