Allan Williams built America’s first roadside rest area — here’s the high-speed tale of a visionary in highway travel and safety.

Born in Michigan, "Renaissance man" Allan Williams proved an innovator in highway engineering as his home state emerged the global center of auto travel.

The Motor City ignited the roar of the 1920s.

Chrysler, Ford and General Motors, each in Detroit, Michigan, emerged as the world's three biggest automakers early in the Roaring '20s. Customers needed somewhere to go to make their engines purr – and a safe, convenient way to get there.

The job fell upon the shoulders of small-town Michigan visionaries who paved the way for the automobile to leave the city and become synonymous with the open American highway.

Allan Williams, the first-ever highway engineer in rural Ionia County, proved perhaps the most influential among them.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO STITCHED TOGETHER THE STARS & STRIPES, BETSY ROSS, REPUTED WARTIME SEDUCTRESS

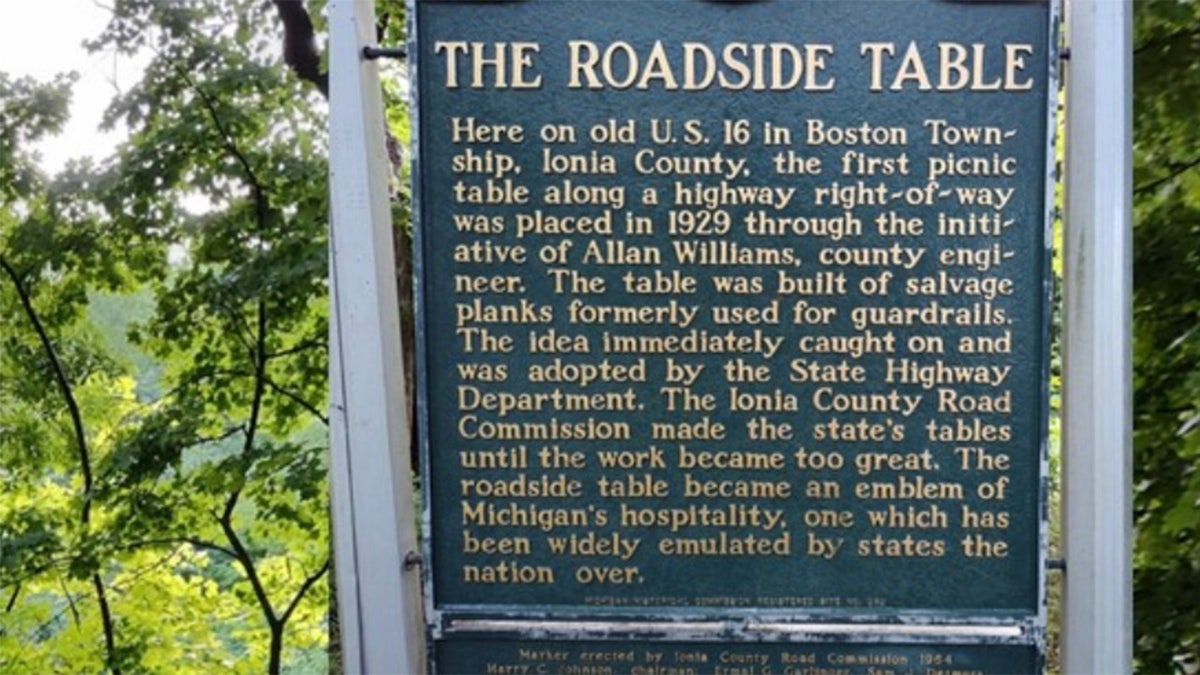

He conceived and created America’s first roadside rest area in 1929. The idea took off faster than a big-block Motown muscle car 40 years later.

The highway rest stop, however, was only the most visible of the many contributions Williams made to the speed, safety and convenience of the American highway system we all benefit from today.

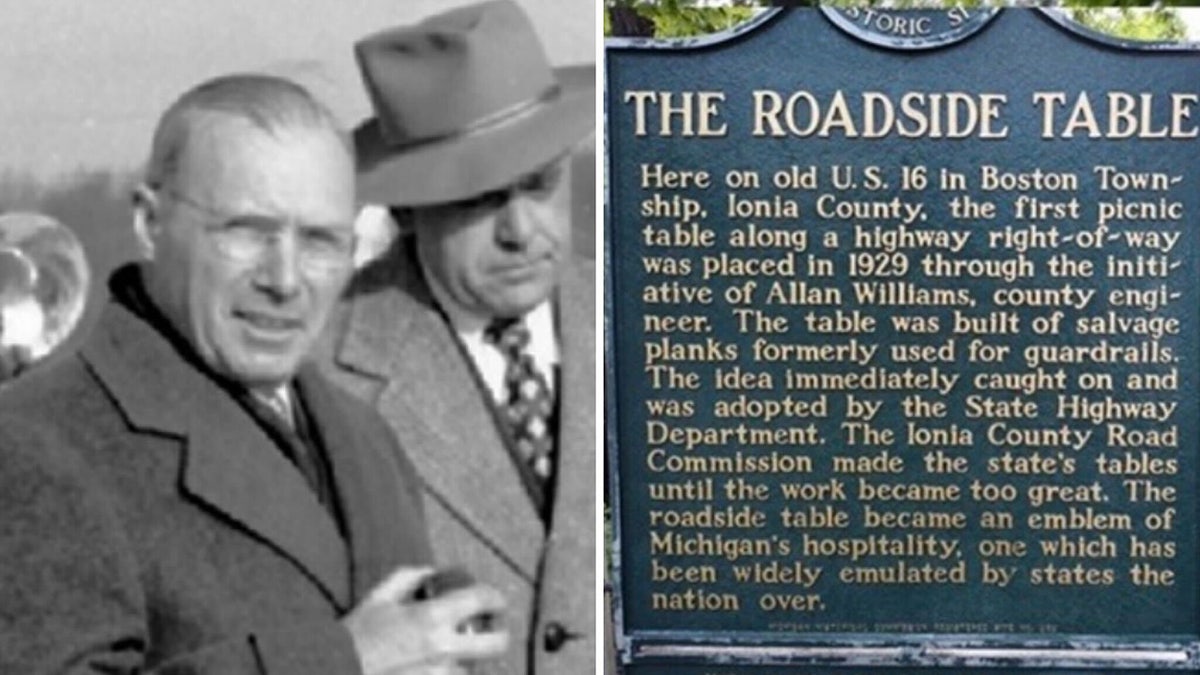

Allan Williams, standing, of the Ionia County Road Commission speaking at a City of Ionia, Michigan, bridge dedication luncheon. (Michigan Department of Transportation)

"He was living at a time when he had the ability to really do some big things and make some big changes in Michigan, but also actually in our nationwide history," Sigrid Bergland, a historian with the Michigan Department of Transportation, told Fox News Digital.

Highway road maps, road signs and even snow plows were all influenced by his curiosity, intellect, varied skills and vision.

"He really was a Renaissance man."

Williams also proved a civic leader in both peacetime and wartime.

He helped improve the roads less traveled in his small-town life.

"He was really an interesting Michelangelo-type of all-around interesting guy who did a lot of different things over his lifetime and who just happened to be a transportation engineer," said Bergland. "He really was a Renaissance man."

Fun, freedom and ‘automobiling’

Allan Mackenzie Williams was born on Jan. 26, 1892 in Ludington, Michigan, to Joseph and Isabelle (Cogswell) Williams.

The future American roadmaster apparently inherited his varied interests and natural gifts for fixing things from his father.

Roadside picnic on the way to Wisconsin, 1917. Mary E. Smith is seated with a friend on a white blanket with thermoses and a picnic basket. Their automobile is parked on the side of the road next to a fence. (Historical Society/Getty Images)

The elder Williams jumped from a career as a camp cook to one as an electrical engineer, according to the Michigan DOT.

"He opened and ran an electrical shop," the state agency notes, "and went on to wire the first home in Ludington with electricity."

The younger Williams studied engineering at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor before transferring to Kalamazoo College, in Kalamazoo.

He found his life's calling in 1919, still only in his 20s, when he was hired as county engineer for the Ionia County Road Commission.

Few roads were even paved at that point, notes Bergland of Michigan DOT.

Chuck "The Viking" Hayden, publisher of the travel blog restles-viking.com, at the first American highway rest stop: Route 16, Ionia County, Michigan. (Martha and Chuck Hayden/restless-viking.com)

But automobiles built 130 miles east in Detroit were getting more affordable, growing in popularity and spilling out across the American countryside.

"The elite chauffeur-driven crowd was about to be surpassed by a general public that wanted the fun and freedom that came with ‘automobiling,’" auto journalist Nick Kurczewski wrote in 2016.

The "public … wanted the fun and freedom that came with ‘automobiling.’"

Michigan highway engineers were the first people in a position to witness, then shape the future of automobile travel. Convenience was an early need.

Williams, apparently before the winter of 1928, "saw a family trying to eat a picnic lunch from a big tree stump alongside their parked automobile on one of the roads under county jurisdiction," American Road Builder magazine reported in 1957.

Detroit, Michigan: Ford family and friends out for a drive on Detroit street in the 1906 Model K-6 cylinder auto. Left to right: Henry Ford, Leroy Pelletier, Clara Ford, Edsel Ford, and a telephone operator. (Getty Images)

"[They] had an appetizing snack spread out on a white cloth on the stump, but they couldn’t really enjoy the food because they couldn’t sit around their makeshift table, and had to content themselves with standing around or sitting on rocks or bare ground to eat their food."

Williams had some extra wood lying around the Ionia Country Road Commission garage – and a vision.

‘Thought he was going to get a bawlin’’

The automobile first became a major part of the American landscape in the 1920s.

The number of cars registered in Michigan alone more than quadrupled during the decade, from 326,000 in 1919 to 1.4 million in 1919.

Williams witnessed similar scenes of travelers eating on the side of the road with increasing frequency.

A General Motors assembly line showing an early engine drop, circa 1920. (Fotosearch/Getty Images)

"An outdoorsman himself, he decided that people should have better facilities for resting and refreshing themselves along the highways," according to the American Road Builder account.

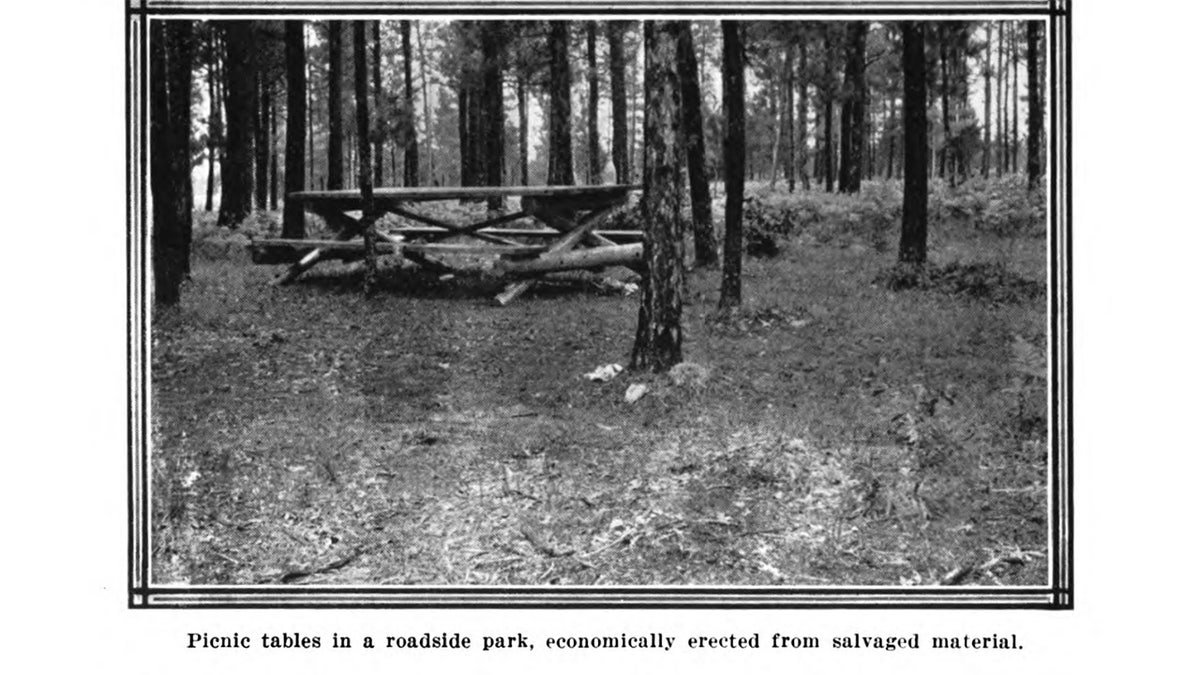

"During the winter months, when some of his snowplowing crews were standing by at the county garage waiting for an expected storm, he put them to work knocking together picnic tables from odd lengths of 2x4 scrap lumber."

For more Lifestyle articles, visit www.foxnews.com/lifestyle

He used "leftover guardrail wood or other surplus timber" according to Michigan DOT, while the tables "probably had plenty of splinters sticking out," notes Bergland.

Allan Williams, the county engineer for the Ionia County (Michigan) Road Commission, created the first highway rest area in the U.S. on Route 16 in Michigan in 1929. (Michigan Department of Transportation)

The tables were painted green and placed on Route 16, three miles south of the Village of Saranac.

"My dad thought he was going to get a bawlin’ out for using that planking," the engineer’s son, Colin Williams, then 84, said in a 2011 interview with MLive.com.

William’s roadside rest area, in today’s terms, went viral.

The "bawlin’" never came.

Instead, acclaim came from far and wide. Williams’ roadside rest area, in today’s terms, went viral.

"The state highway department received more than 500 pieces of written feedback at table locations, from motorists as far away as Washington, Florida and Texas," according to the MLive.com account.

Williams’s vision for highway respite spread about as fast as construction crews could pour the concrete for new roads.

A sign on Route 16 in Ionia County, Michigan, marks the site of the first highway rest stop in the United States. (Martha and Chuck Hayden/restless-viking.com)

Nearly 1,500 picnic tables had been placed around Michigan by 1937, many of the earliest built by Williams’ staff in Ionia County.

The state eventually took over the responsibility. The roadside picnic table total in Michigan reached 2,500 by 1947.

There are 1,400 full-service highway rest areas just along U.S. Interstate highways today, according to InsterstateRestAreas.com.

They offer countless picnic tables and seats among them.

‘Just some guy in small-town Michigan!’

Allan Williams passed away on June 3, 1979.

He was 87 years old and is buried in Lakeview Cemetery in his hometown of Ludington.

Allan Williams, far left, at M-66 bridge dedication ribbon cutting ceremonies in Ionia, Michigan. (Michigan Department of Transportation)

"Michigan was definitely the location of many ‘firsts’ in transportation — and especially highway — history," Chris Bessert, the publisher of MichiganHighways.org, wrote in an email to Fox News Digital.

Williams, he writes, was at the center of it all.

"He designed and issued the first state highway road map … He championed the construction of highways on rights-of-way wider than the standard 66-foot space used to that point, he designed Michigan's state highway route marker and widened its use, and a variety of other firsts."

"The state highway department received more than 500 pieces of written feedback at table locations."

William's impact was also felt close to home.

"He left a legacy in Ionia County," traveler bloggers Martha and Chuck "The Viking" Hayden write on restless-viking.com.

He served for many years as president of the Ionia County Free Fair, still one of the largest in the state, helped engineer Ionia County Airport, and was chairman of the county hospital board.

The first highway rest stop in 1929 consisted of a few roadside picnic tables on Route 16 in Michigan. They quickly became an American phenomenon. South of the Border in Dillon, South Carolina, is one of the nation's gaudiest roadside attractions. John Margolies Roadside America Photograph Archive, 1986. (Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

When the United States entered World War II, Williams oversaw Ionia County's efforts to turn scrap metal into munitions.

"He was very civically minded, very interested in helping people and finding different ways to give back to people and to contribute to his community," said Bergland of Michigan DOT. "He was a big-picture guy."

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

Gov. William Milliken honored Williams with a Michigan Tourism Award in 1976, recognizing the contributions the engineer’s work made to encouraging visitors to the state.

There is some dispute, however, over the Williams rest-area origin story.

"Some documentation indicates that Connecticut established its first site in 1928," reports RestAreaHistory.org. "More solid evidence, however, points to Michigan and a site created in 1929."

Other evidence suggests that Herbert Larson, a road commissioner in Iron County, on Michigan's Upper Peninsula, erected roadside picnic tables as early as 1919.

Allan Williams, far left, was the first engineer for the Ionia County (Michigan) Road Commission when he conceived the first U.S. highway rest area in 1929. A sign marks the American roadside landmark today on Route 16 in Michigan. (Michigan Department of Transportation; Martha and Chuck Hayden/restless-viking.com)

But Larson's was a standalone occurrence, according to Bessert, while Williams created what became a state and then national phenomenon.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

"Williams' role in the early development of Michigan's highway system was copied and duplicated around the world," writes Bessert.

"It’s something that shouldn’t be minimized. And this was just some guy in small-town Michigan!"

To read more stories in this unique "Meet the American Who…" series from Fox News Digital, click here.