Coronavirus’ similarities with SARS are reassuring: Dr. Marc Siegel

Fox News medical correspondent Dr. Marc Siegel discusses new research coming out on coronavirus showing its commonalities with SARS, which eventually died out, and whether temperature can impact this virus.

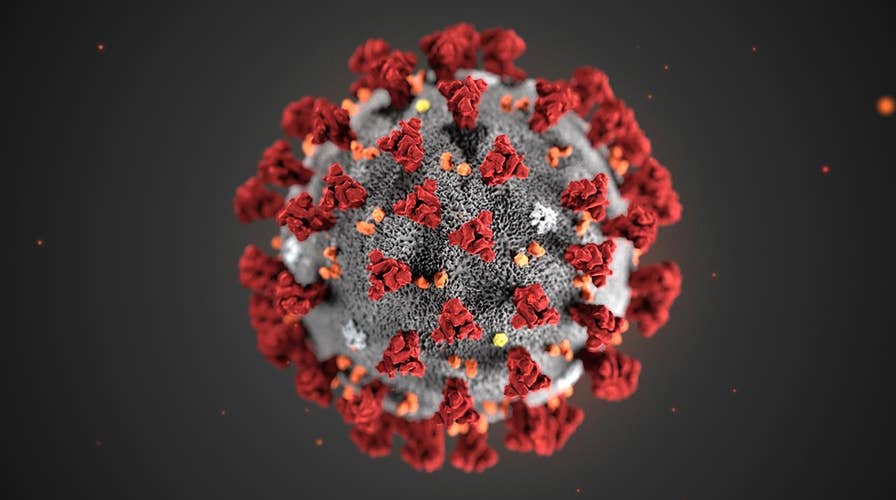

As the novel coronavirus continues to spread across the globe, with more than 100,000 cases reported worldwide, financial markets plummeting and travel disrupted, an end to what the World Health Organization (WHO) has recently declared a pandemic seems like a far-off dream.

But there are ways in which the outbreak could end — though virologists and epidemiologists are not exactly sure how. Read on for a look at some ways the U.S. and the rest of the world could see an end to the outbreak of the novel virus or COVID-19, according to experts.

MAYO CLINIC DEVELOPS CORONAVIRUS TEST TO 'HELP EASE SOME OF THE BURDEN' ON CDC, STATE LABS

Containment

Proper containment measures could end the coronavirus outbreak, said Dr. William Schaffner, the medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. He cited the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in the early 2000s as an example.

“The SARS outbreak was controlled through close coordination between public health officials and clinicians who were able to diagnose cases, isolate infected patients, trace their contacts, and implement strong infection control policies,” he said in an interview with Fox News.

Containment efforts in China appear to be working, at least according to the country’s official figures. The number of cases in the country has reportedly dwindled, with just 99 new cases reported last weekend compared to some 2,000 a day a couple of weeks ago, The New York Times reported.

Hubei province — which is home to the city of Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak — was placed on lockdown, affecting some 60 million people. Elsewhere in the country, stringent travel and quarantine measures were put in place. The WHO has praised the Chinese government's containment efforts, though some have questioned the toll such efforts have taken on its citizens' livelihoods. There’s also the question if similar measures could work in other countries seeing outbreaks.

ALABAMA REPORTS FIRST CORONAVIRUS CASE

In the U.S., however, some epidemiologists and virologists have cast doubt on whether containment efforts are working.

“Two or three weeks ago, we were still hoping for containment,” Tara Smith, an epidemiologist at Kent State University, told Vox. “We’re really past that. ... The horse is out of the barn.”

Another expert said the various instances of community-based transmission in the U.S., as well as cases of asymptomatic patients spreading the virus, suggests that it not be containable at all. In response, officials in every country across the globe, “should [have begun] pandemic preparation. This would include scaling up diagnostic testing, preparing hospitals, and crafting public health messages,” Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, also told the outlet.

Containment efforts in the U.S., specifically, may also be hampered by testing kit shortages and a fear that the materials needed to make more may soon run dry.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has faced backlash for its slowed rollout of testing kits, some of which were said to be faulty. Officials estimate that only around 8,500 people in the U.S. have thus far been tested for the pathogen, sparking fear that the numbers who have contracted it – and are continuing the spread – may be drastically higher. Meanwhile, other countries encountering a severe outbreak, such as South Korea, are said to be testing upward of 10,000 people per day.

Additionally, a ProPublica investigation found that the CDC chose to develop its own testing kits rather than using those from the WHO, a decision that possibly caused the federal agency to lose “valuable weeks that could have been used to track its possible spread,” in the U.S., the outlet found.

The virus infects the most susceptible

The outbreak could end after the virus infects those who are most susceptible, and those who survive it build immunity, said Schaffner.

“An outbreak can dwindle once the virus has infected most of the people who are susceptible to it, because it has fewer targets, as was the case with the Zika virus outbreaks in recent years,” he said.

The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic is another example. As Live Science reported, cases began to trickle off as WWI ended and soldiers dispersed — though not before the flu reportedly killed more U.S. soldiers than any battle during the Great War.

"What happens typically is that enough people get the bug that there just aren't enough susceptible people to keep the chain going,” Joshua Epstein, a professor of epidemiology at New York University, told Live Science.

Warmer weather

There is a chance that cases of the coronavirus could dwindle as the weather warms — but it’s not yet totally clear if spring and summer will bring an end to the outbreak.

“If COVID-19 behaves like other respiratory viruses, including influenza (flu), it could abate as the weather gets warmer,” Schaffner said.

But it’s too early to know for sure. Scientists are still working to understand the novel virus, which has sickened more than 130,000 people globally as of March 13.

"We hope that the gradual spring will help this virus recede, but our crystal ball is not very clear. The new coronavirus is a respiratory virus, and we know respiratory viruses are often seasonal, but not always. For example, influenza (flu) tends to be seasonal in the U.S., but in other parts of the world, it exists year-round. Scientists don’t fully understand why even though we have been studying [the] flu for many years,” he said. “The novel coronavirus was just discovered in humans in December. It is too early to know for certain what the impact of warmer weather will be."

There are at least four pre-existing coronaviruses that are seasonal — but why exactly remains somewhat shrouded in mystery, as is the case for many infectious diseases. For instance, the 2002-2003 outbreak of SARS, which claimed nearly 800 lives at the time, ended in the summer — but a 2004 report on the seasonality of SARS did not establish a clear reason for why that was.

“Our understanding of the forces driving seasonal disappearance and recurrence of infectious diseases remains fragmentary, thus limiting any predictions about whether, or when, SARS will recur,” the authors wrote at the time. “It is true that most established respiratory pathogens of human beings recur in wintertime, but a new appreciation for the high burden of disease in tropical areas reinforces questions about explanations resting solely on cold air or low humidity.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

A vaccine

It’s also important to note that anti-viral treatments or a vaccine could help end the pandemic, but the latter is some 18 months away, officials with the WHO said last month.

"The development of vaccines and therapeutics is one important part of the research agenda. But it's not only one part. They will take time to develop — but in the meantime, we are not defenseless," WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said at the time.

CLICK HERE FOR COMPLETE CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

Kathy Stover, the branch chief for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), also confirmed the vaccine's development in an email to Fox News in January.

Since then, serval major companies — including Johnson & Johnson and Moderna Inc. — have announced similar initiatives.

It could become a seasonal virus

While the pandemic could end, the COVID-19 may never fully disappear. Rather, it could become endemic like the common cold.

“It may become part of the annual cold and flu respiratory season,” Schaffner said.

In this scenario, however, the virus is likely to make less of an impact as it is currently because more people will have immunity to it, as per Live Science.

Fox News' Hollie McKay contributed to this report.