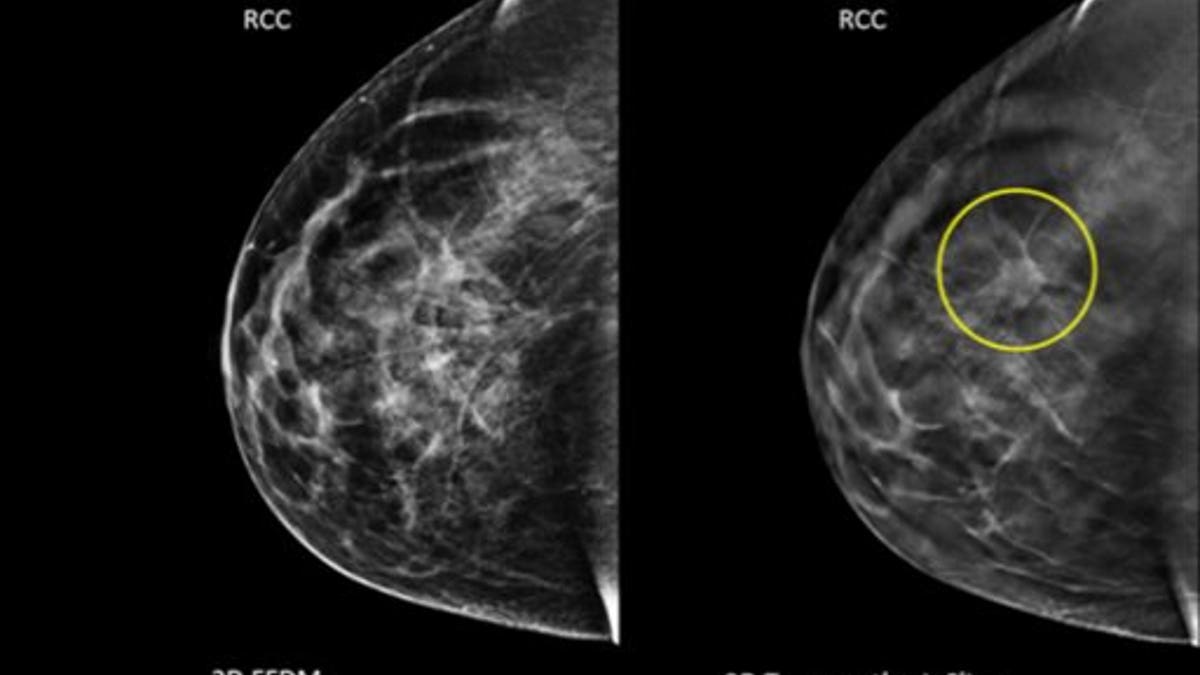

Image taken using conventional mammography and an image using 3D, with a tumor circled that wasn't visible before. (AP)

In 2013, mammogram and colorectal cancer screening rates had stalled and Pap tests were on the decline, with many eligible U.S. adults not getting the recommended tests, according to a new report.

Among people who should be regularly screened for breast, colon and cervical cancer according to current guidelines, many are not getting the tests as often as recommended or at all, researchers say.

“About 20 to 40 percent of people in these groups reported not being screened,” said lead author Dr. Sue Sabatino of the Centers for Disease Control Division of Cancer Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

Many barriers can contribute to the lack of screening, she said – insurance coverage seemed to be an important factor.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force – a government backed independent panel of experts who review medical evidence - recommends that women ages 50 to 74 have a mammogram to screen for signs of breast cancer every two years.

The USPSTF stirred controversy in recent years when it concluded there was insufficient evidence for the value of regular mammograms before age 50. And the panel last month clarified the recommended intervals for cervical cancer screening (see Reuters Health story of April 30, 2015, here: reut.rs/1He5GeQ).

The study team looked at whether eligible people in the U.S. were meeting Healthy People 2020 targets for cancer screening, which are based on USPSTF recommendations.

Those include that women age 21 to 65 have a Pap smear every three years to screen for abnormal developments of the cervix, and everyone age 50 to 75 have one of the available screens for colon cancer every one to 10 years, depending on the type of test they choose.

For to the National Health Interview Survey of 2013, randomly selected adult representatives of U.S. families were asked to recall their screening histories.

One in four women said they were not up to date on mammograms and one in five were not up to date on cervical cancer screening, while two in five adults said they had not had a recent colorectal cancer screen, according to the results in CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Less than 25 percent of people without insurance said they were up to date on colorectal cancer screening, compared to 60 percent of those with private insurance.

Mammogram and colorectal cancer screening rates essentially stayed the same between 2008 and 2013, and Pap smear rates declined slightly, with all still below Healthy People 2020 targets.

College-educated women and those earning more than 400 percent of the federal poverty threshold did meet the Healthy People 2020 targets for mammograms, the authors found.

“For patients, one thing they can do is talk with their health care providers about what screenings they need, when they should start and how often they should happen,” Sabatino said.

“For colorectal cancer screening we know there is more than one recommended test, so clinicians should discuss with patients what is best,” she told Reuters Health.

Together, breast, cervical and colorectal cancers killed more than 100,000 people in the U.S. in 2011, according to the U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group.

It is troubling to see these important screening tests stall or decrease, said Roshan Bastani, a health psychologist at the University of California, Los Angeles David Geffen School of Medicine who was not part of the CDC report.

“For breast cancer and cervical cancer, screening tests have been around a long time and you would expect to see a continued increase,” Bastani told Reuters Health by phone.

The rate of colorectal cancer screening in particular is very, very low, and colorectal cancer screening does more than just detect early signs of cancer, she said. The test itself can be preventive, if polyps are removed before they become cancerous.

“I’m not sure that message is clear to the public,” Bastani said.

The U.S. health system needs to find ways to communicate a clear, simple message about screening to the public, and give physicians and support staff the language and tools to communicate this message, she said. Breast cancer advocacy groups did a great job of promoting mammography in the U.S., but as yet there is no such advocacy for colon cancer, Bastani noted.

“We need to redouble our efforts, this is a wake-up call,” she said.