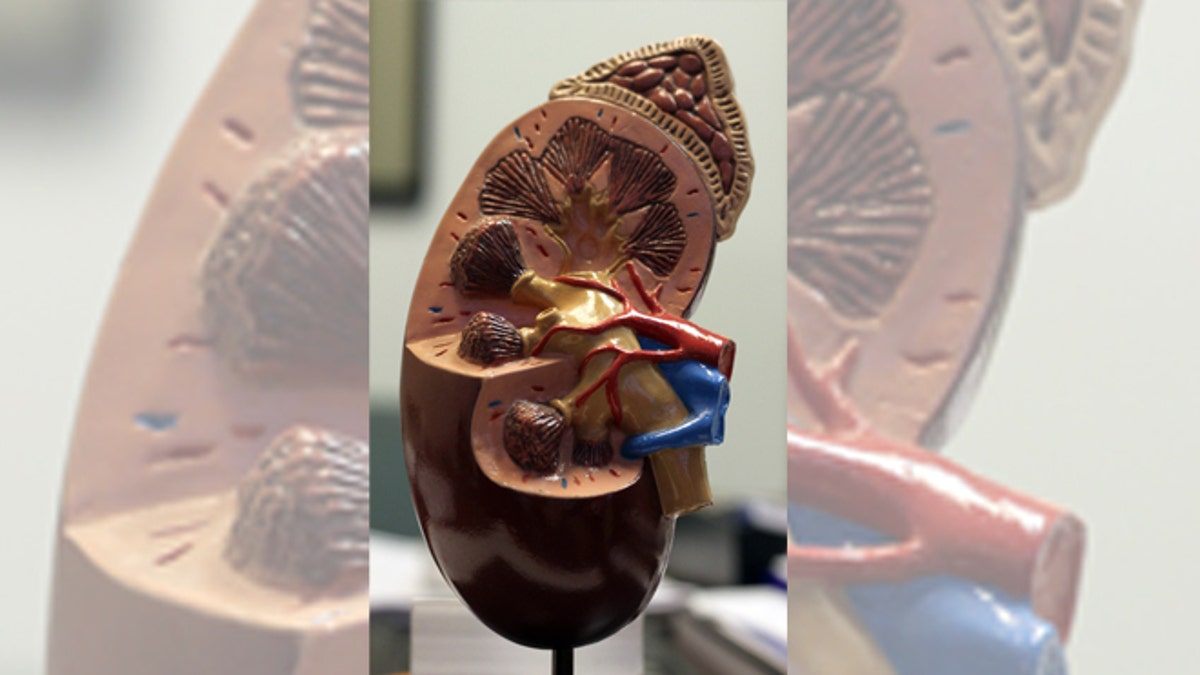

(Courtesy of the National Kidney Foundation)

After kidney transplants, the risk of death over the next year falls just as much among obese kidney failure patients as it does for thinner people, says a new study.

Researchers found that the risk of an obese person dying during the year after a kidney transplant dropped about 66 percent, compared to obese people who remained on dialysis. That's equal to the benefit thinner people get from a transplant.

"This is good and important news with the changing environment and increasing regulation of transplantation. It confirms the benefit of transplantation in this high-risk group," said Dr. John Gill, the study's senior author from the University of British Columbia and St. Paul's Hospital in Vancouver, Canada.

The researchers write in the American Journal of Transplantation that kidney transplantation is the preferred treatment for people with end-stage kidney disease.

Compared to dialysis, an arduous process for removing waste from a patient's blood several times a week, transplants are tied to a lower risk of death and a better quality of life.

But past research has found that obese people with kidney failure do better on dialysis than thinner people, and that they're more likely to die following organ transplants - both issues that would alter the risk-benefit calculation for the decision to do a kidney transplant in those patients.

For men and women, body mass index (BMI) - a measure of weight relative to height - of 30 and above is considered obese by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A five-foot, nine-inch person would have a BMI of 30 at 203 pounds and a BMI of 40 above 271 pounds.

The most recent previous analysis of kidney transplants in obese patients found that their survival benefit is comparable to that of thinner patients, but the result was based on data from the 1990s.

Since then, according to the researchers, the number of obese people with end-stage kidney disease has grown and the selection of transplant patients has evolved.

For the new study, the researchers analyzed data on U.S. adults with end-stage kidney disease, who had either a kidney transplant or their first dialysis session between April 1995 and September 2007.

About 60 percent of the 145,629 patients with a BMI below 30 received a transplant, compared to about half of the 62,869 obese patients.

The researchers found that 12 percent of the thinner patients who received a transplant and 34 percent of those on dialysis died within about three years.

That compared to 14 percent of the obese patients dying after a transplant and 28 percent dying on dialysis.

Overall, thin and obese people's risk of death in the year following their transplant fell by similar amounts, compared to those who remained on dialysis.

"Another important aspect of this study shows that people do benefit from living-donor transplantation - especially among obese patients," Gill told Reuters Health.

But the researchers found that the benefits of transplant in severely obese people - those with BMIs of 40 and above - weren't as great as the benefits in thinner people. Whether African Americans with a BMI over 40 benefitted at all could not be determined because there were too few in the study population.

Other high-risk groups, however, did show a benefit, including diabetics, Gill said.

"This is meant to say we're not to preempt transplantation in obese patients," said Gill, who added that this shouldn't stop doctors from encouraging patients to lose weight.