Thinking beyond Ebola: Will these viruses be the next public health crises?

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}

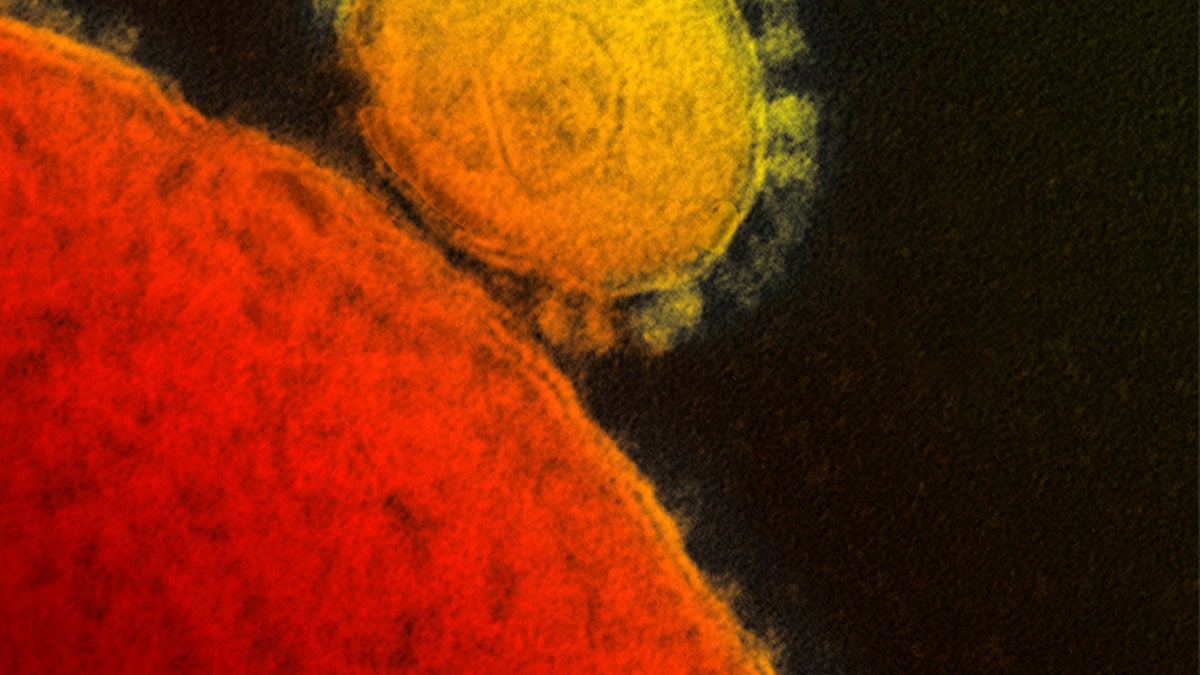

This undated electron microscope image shows a novel coronavirus particle, also known as the MERS virus, center. (AP Photo/NIAID - RML)

As the Ebola epidemic rages on in West Africa— where the virus has already claimed the lives of more than 5,000 people— epidemiologists in the United States are speculating over which ailments could go viral next.

In 2009, the U.S. federal government established the PREDICT project, under its Emerging Pandemic Threats program, to detect and discover zoonotic diseases in wildlife settings that have the potential to impact humans.

Dr. Stephen Morse, professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, served as co-director for PREDICT for the first five years following the project’s inception.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}“We’ve never really been able to predict any emerging infection in advance before it reaches the human population,” Morse told FoxNews.com.

“[With PREDICT] we’re attempting to look at what’s out there and try to make some understanding of what might have the possibilities to become the next Ebola or the next SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome),” Morse said. “The idea is to get enough information to understand and develop some criteria and some framework for prediction. But we can’t do it all— even with something as mundane as influenza.”

Hundreds of new infections are reported around the world each week, but distinguishing which illnesses may become a problem from what some scientists call “viral chatter” can pose challenges, said Marc Lipsitch, epidemiology professor and director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard University School of Public Health.

“You can’t really just watch the known viruses and hope to get it right because that means you never pick up the surprises,” Lipsitch told FoxNews.com, but “viruses are major candidates for concern because they evolve genetically over a very short time span, and sometimes the consequence of that is they adapt to spread to humans.”

Historically, some of the world’s most devastating epidemics can be traced back to animals— from the flu, hosted in pigs and birds, to Ebola and its family member Marburg, which scientists believe lived first in bats until humans became infected through poorly cooked meat or direct contact with the animals’ bodily fluids.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Viruses such as SARS, MERS, the flu, and even Ebola are made of RNA, not DNA, genetic material, which enables them to adapt and change at a quick, often unpredictable pace.

“If you had to put your money [in] one place, it would be on RNA viruses,” Lipsitch said, “but you can’t limit it to that because nature doesn’t follow those rules."

“What really allows epidemics to be explosive is when people become the sources because then our normal activities, whether it’s breathing or sexually transmitted diseases, become the way that it becomes transmittable.”

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Viruses such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and influenza are among the ailments that Lipsitch and Morse say have the potential to become more infectious in the United States.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Doctors first identified SARS in 2003 in China, where the respiratory condition had a 10 percent fatality rate and resulted in about 8,000 cases and 900 deaths after it spread to Canada, Morse said.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Symptoms include a fever of 100.5 F or higher, as well as a dry cough and shortness of breath.

Older people who had underlying health problems were particularly at risk during the outbreaks in China and Canada. The virus is transmitted by respiratory means, but contact must be close. “It’s not nearly as airborne as the flu,” Morse said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there have been no new reported cases of SARS since 2004.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}“I don’t think it’s gone,” Morse said. “A couple of years ago, some colleagues found some of the virus in bats, which means there’s a virus just like SARS that’s already out there that can infect humans and re-evolve.”

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV)

The first cases of MERS, SARS’ cousin, an illness produced by the virus MERS-CoV, were reported in April 2012 in Jordan. Globally, 852 cases and at least 301 deaths— the vast majority in the Arabian Peninsula— due to MERS have been reported to the WHO since then. The virus most recently struck Saudi Arabia, where a handful of cases have been reported since last summer.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}MERS symptoms include fever, cough and shortness of breath, according to the CDC. Some people also have reported gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea and nausea or vomiting.

According to the CDC, the virus has a 30 percent fatality rate. Most of the people who have died of MERS had an underlying medical condition.

Camels account for about 20 percent of the known transmission cases, and health care workers exposed to infected people account for another 20 percent, Morse said, “so that leaves about 60 percent of the cases for which we have no history.”

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}In May 2014, the U.S. reported its first two imported case of MERS. The cases were unlinked, but both were of travelers from Saudi Arabia, according to the CDC.

Lipsitch said MERS “doesn’t demonstrate the ability to produce pandemic,” and it has been shown to transmit inefficiently.

Influenza

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}“Clearly flu that comes from birds and pigs and other animals is something that has the potential to [become] pandemic,” Lipsitch said.

Avian influenza A(H7N9) was detected in China in 2013 after people reported flu-like symptoms but tested negative for previously identified strains. A previous strain, H5N1, was first confirmed in Pakistan, and has since spread to 15 other countries and claimed 393 deaths, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

H5N1 hasn’t impacted the U.S. yet, and it is mostly spread through contact with infected poultry or contaminated environments. Human transmission is rare, according to the WHO.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}Influenza H3N2, on the other hand, was reported twice in the United States in August. Both people infected said they had close contact with swine in the week before the illness, and no ongoing human-to-human transmission has been identified.

“Owing in part to the emergence of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, there is enhanced surveillance for non-seasonal influenza viruses in both humans and animals,” the WHO wrote in its most recent report. “It is therefore to be expected that influenza A(H5N1), A(H7N9), and other subtypes of influenza viruses will continue to be detected in humans and animals over the coming months.”

The WHO estimates that seasonal influenza occurs globally at a 5 to 10 percent rate among adults and a 20 to 30 percent rate in children. Worldwide, these annual epidemics are estimated to result in about 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness, and about 250,000 to 500,000 deaths.

{{#rendered}} {{/rendered}}The seasonal flu is transmitted from person to person by air through droplets when an infected person produces droplets when they cough, sneeze or talk. It can be spread to others up to about 6 feet away, according to the CDC.

To avoid the flu, the CDC recommends getting vaccinated, maintaining proper hygiene and staying away from infected people.

“The flu we take very much for granted,” Morse said, “because in 1918, the [influenza] pandemic was arguably the greatest natural disaster in human history. There were more than 50 million deaths that we know about— and that only had a mortality rate of in the low single digits. We argue whether it’s 1 percent or 2 percent, but when you have literally half of the world’s population infected, a very small number is still very big.”