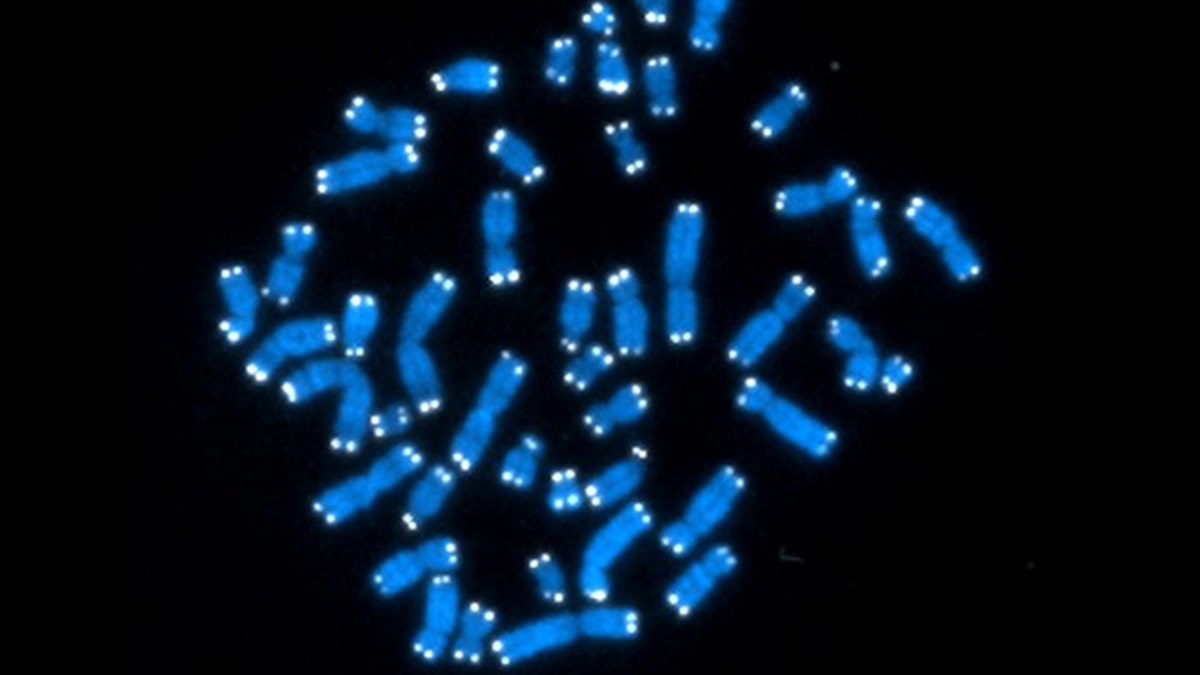

Sept. 5, 2012: The 46 human chromosomes, where DNA resides and does its work. Each chromosome contains genes, but genes comprise only 2 percent of DNA. (AP Photo/National Cancer Institute)

WASHINGTON – More cancer patients are getting the genes in their tumors mapped to help guide their treatment. New research suggests that isn't always accurate enough, and a second test could help ferret out the culprit genes.

Cancer involves two sets of genetic code - your own and your tumor's. A study published Wednesday found that mapping only the tumor's genome could provide misleading results and lead to treatment that's less likely to work.

Comparing the two genomic sequences ensures that a mutation found in a tumor really helped fuel that cancer and isn't a harmless mutation sitting in the person's normal cells, too, explained lead researcher Dr. Victor Velculescu of Johns Hopkins University.

That's important as scientists increasingly design drugs to target specific tumor mutations.

"We cannot have precision medicine without precision genomics. We can't expect physicians to provide the right therapy to the right patients if we can't obtain accurate results in our diagnostic tests," Velculescu said.

Tumor genetic tests often are simple, looking just for single gene mutations or "hot spots" that match one of the first targeted therapies to hit the market. That's not the worry here. Velculescu's concern is broader genomic sequencing, or mapping, of potentially hundreds of suspicious gene variations.

This next-step testing isn't common yet, but it is expected to increase rapidly in the next few years. Some clinics sequence both the tumor and the normal tissue, while others sequence only the tumor.

To see if tumor-testing alone is enough, Velculescu's team analyzed records from 815 patients with 15 different types of cancer who had had both types of sequencing.

Nearly two-thirds of mutations found in the tumor-only testing turned out to be false-positives - present in patients' normal tissue, too, when both genetic maps were compared, the team reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine. Then the researchers tried a more targeted approach, looking just for certain cancer-linked genes, and still one-third of abnormalities were false-positives.

The two-part sequencing takes more effort - remembering to get a patient sample of healthy tissue - and costs more, said Velculescu, who co-founded a testing company, Personal Genome Diagnostics.

The study points out a key consideration as this genetic testing is poised to increase, said Dr. Matthew Ellis, a breast cancer genomics expert at Baylor College of Medicine.

"If you want to work out how the cancer recoded its genome to become a cancer, you have to be able to compare the cancer genome with the genome you inherited from your mom and your dad," said Ellis, who was not involved with the new study.

But a large gene testing company, Foundation Medicine, said most of the false-positives in the study were mutations of unknown significance that wouldn't play a role in doctors' treatment decisions anyway. Chief scientific officer Phil Stephens said his company can separate out the mutations driving a tumor without the extra testing step.

However the testing question turns out, Baylor's Ellis said the wide variety of genetic abnormalities the Hopkins team uncovered also highlights the need for more research to match medications with these variants so that more people can benefit.

The National Cancer Institute is beginning a major study to do that, part of a government push for precision medicine.