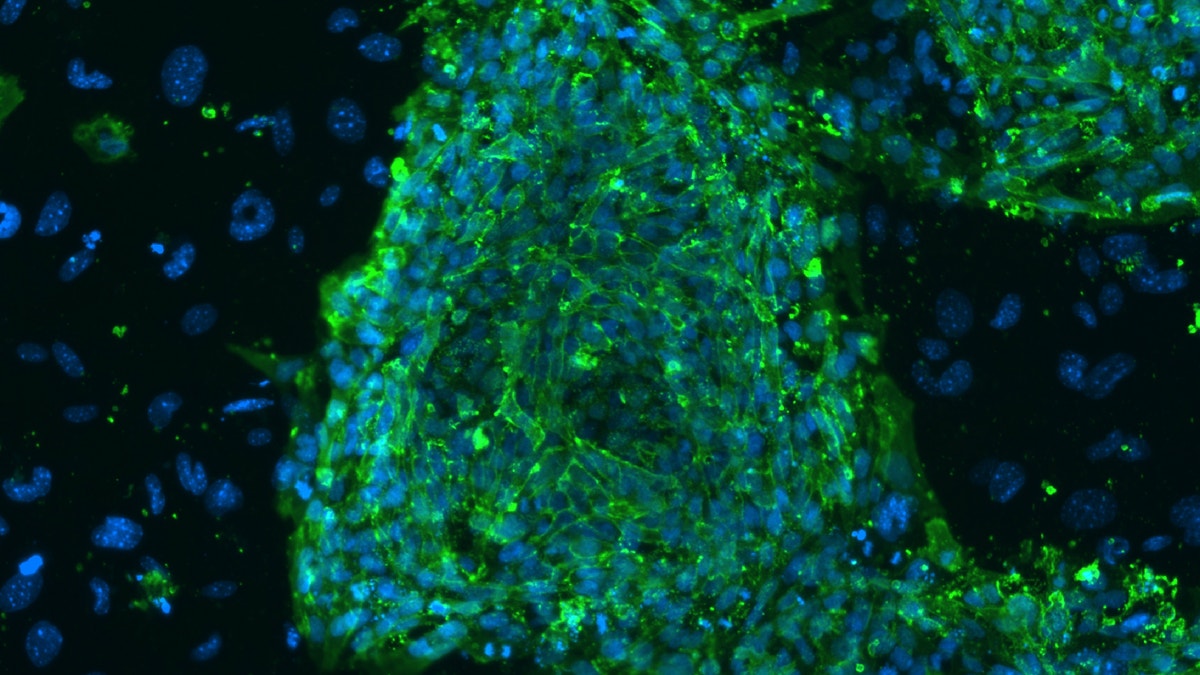

A fluorescent microscope image shows human embryonic stem cells in this photo taken at Stanford University and released by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. (REUTERS/Michael Longaker/Stanford University School of Medicine/California Institute for Regenerative Medicine/Handout)

Some Alzheimer’s disease researchers are using stem cells in a novel way—as a model of the disease outside the human body, enabling more efficient testing of experimental drugs in the lab rather than in clinical trials with people.

Finding a drug to slow the onset of Alzheimer’s, the major cause of dementia in older people, has been frustratingly elusive. That is partly because animal testing, where most research begins, doesn’t often produce results that predict very well what will happen to people with Alzheimer’s. And clinical trials of drugs in humans are costly and time consuming.

Though still early days in the field, scientists at the University of California, San Diego, Harvard University and a number of other institutions along with a growing bevy of biotech and pharmaceutical companies, are developing better ways to study the disease outside of the human body and without using animals.

In an early development, scientists at University of California, San Diego used stem cells, which can differentiate into a number of specialized cell types, to create neurons with characteristics of Alzheimer’s. Then they tested two experimental drugs, including one that had previously been withdrawn from a clinical trial because it seemed to worsen disease symptoms rather than help. In testing the drug on the stem cell-derived neurons, the researchers found that for certain patients with a particular genetic mutation, the dosage received in the clinical trial was likely ineffective.

Such “in vitro” testing of Alzheimer’s drugs using human stem cells could potentially help researchers more quickly identify compounds that shouldn’t move forward in development, as well as identify accurate doses of medicine for people in clinical trials, says Shauna Yuan, a professor in the department of neurosciences at UCSD and lead researcher in the project.

For instance, scientists could test actual human brain cells more extensively in the lab, rather than jump quickly from animals to large, expensive human trials, which have become common in the field.

In the realm of treatment, one approach is to use a patient’s own stem cells to repair damaged tissue—creating treatment specific to that individual. With some diseases, stem cells produce new, healthy tissue in place of damaged tissue, although it isn’t clear how well that would work in the brain with neurological disorders. Another goal is to create stem cell lines that could be scaled up and used to treat larger patient populations, similar to the way small-molecule drugs and biologics therapies are used now.