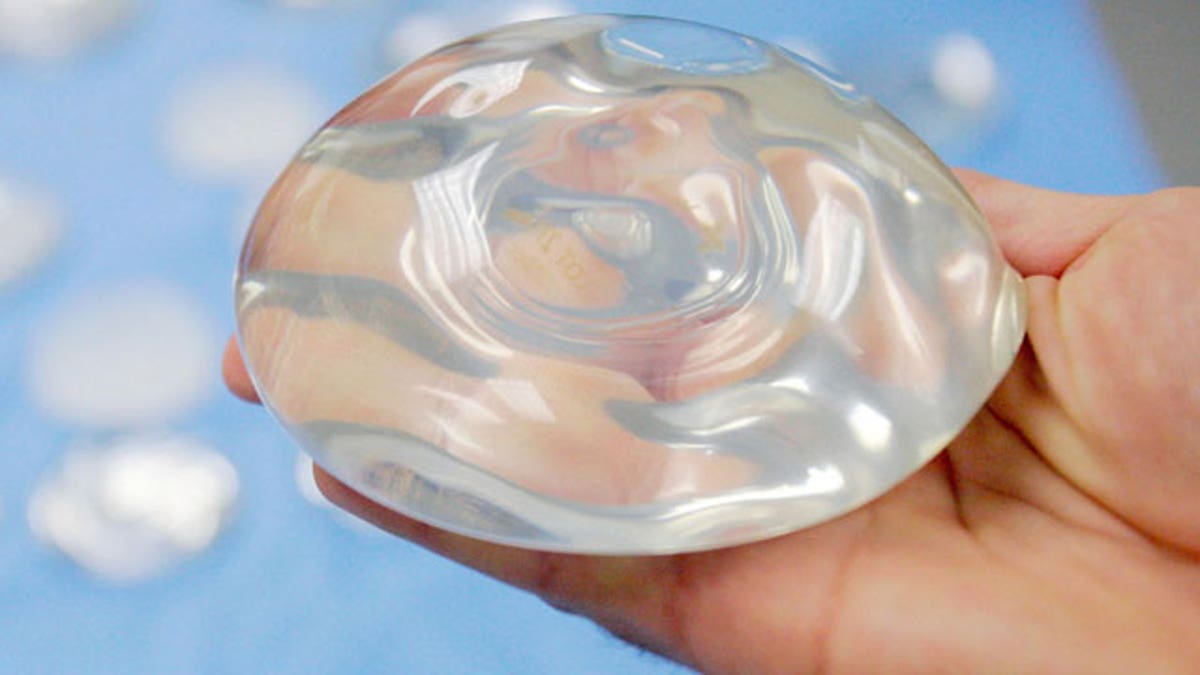

Silicone gel breast implant (AP)

Good evidence on the safety of silicone gel breast implants is still lacking almost 10 years after they were reintroduced to the U.S. market, researchers report in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

"Owing to the flaws and inconsistencies among the studies reviewed, further investigation is required to determine whether any true associations exist between silicone gel implants and long-term health outcomes," write the researchers, led by Dr. Ethan Balk of the Brown University School of Public Health in Providence, Rhode Island.

Breast enlargement was the most commonly performed cosmetic surgery in the U.S. during 2014, with over 286,000 women having the procedure, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Silicone implants are used in about three quarters of those surgeries.

Unlike implants that are filled with saline, silicone implants are filled with gel to look and feel more like natural breasts. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stopped the sale of silicone gel implants in 1992 in response to public concern, but they were reintroduced in 2006.

For the new analysis, the researchers reviewed more than 5,000 studies of health outcomes after breast implant surgery. Thirty-two of the studies met their criteria for inclusion in the new report.

The studies, which came from North America, Europe and Australia, reported on women who received breast implants between 1964 and 2003.

The researchers were interested in possible links between silicone gel breast implants and several types of cancers, connective tissue diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, immune system disorders, blood flow problems, reproductive issues and mental health.

For most outcomes, however, "there was at most only a single adequately (done) study," and the researchers could not find enough evidence to link breast implants to any health conditions.

"Furthermore, because most studies analyzed all breast implants, their findings are not specific to silicone gel implants," the authors reported.

There was a suggestion that breast implants are linked to a decreased risk of breast and endometrial cancers, and that implants were tied to an increased risk of lung cancer, immune system disorders and blood flow problems.

The researchers say larger studies may be able to overcome the gap in evidence, if the authors of those studies could reanalyze their results to tease out the data that are specific to silicone gel implants and account for variables like family medical history, hormone use, weight, depression and substance use.

The new analysis is meant to support the creation of a national breast implant registry from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons and the FDA that will track all breast implants, the researchers write.

The registry will track women's health from the time they receive their implants until the time they get them replaced, said Dr. Rod Rohrich, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

"Hopefully it'll show what the implants do in five, 10 or 15 years, because that's what's lacking in the current data," said Rohrich, who co-authored an editorial accompanying the new analysis.

He also told Reuters Health that women should be reassured that the researchers did not find evidence linking major adverse events to breast implants, "but we're going to be tracking this because we want to make sure we track them long term in case there are any problems."

In another editorial, two Dutch doctors say women's reports of health problems after receiving silicone gel implants deserve further investigation.

"A logical next step would be to focus future studies on this group with unexplained symptoms to identify the underlying role of the immune system and how we might identify women at risk for complications if they were to receive silicone implants," write Drs. Prabath Nanayakkara and Christel de Blok of VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam.

The researchers were unable to respond to questions before press time.