(Photo courtesy Johns Hopkins University)

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University say they have achieved a successful proof-of-concept for a prosthetic arm with fingers that a user may control with the mind.

“We believe this is the first time a person using a mind-controlled prosthesis has immediately performed individual digit movements without extensive training,” senior study author Dr. Nathan Crone, neurology professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, said in a news release.

Details of the feat, published this week in the Journal of Neural Engineering, may offer a model that would one day help individuals who have lost limbs regain movement. The Amputee Coalition estimates there are more than 100,000 Americans living with amputated hands or arms.

“This technology goes beyond available prostheses, in which the artificial digits, or fingers, moved as a single unit to make a grabbing motion, like one used to grip a tennis ball,” Crone said in the release.

Study authors tested the technology on a young man with epilepsy being treated for seizures at Johns Hopkins. Although he wasn’t missing an arm or a hand, researchers used brain mapping to bypass control of those limbs.

They recorded the man’s brain activity— namely, which parts were responsible for moving fingers— through electrodes that were surgically implanted for clinical reasons. The signals also controlled a modular prosthetic limb developed by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

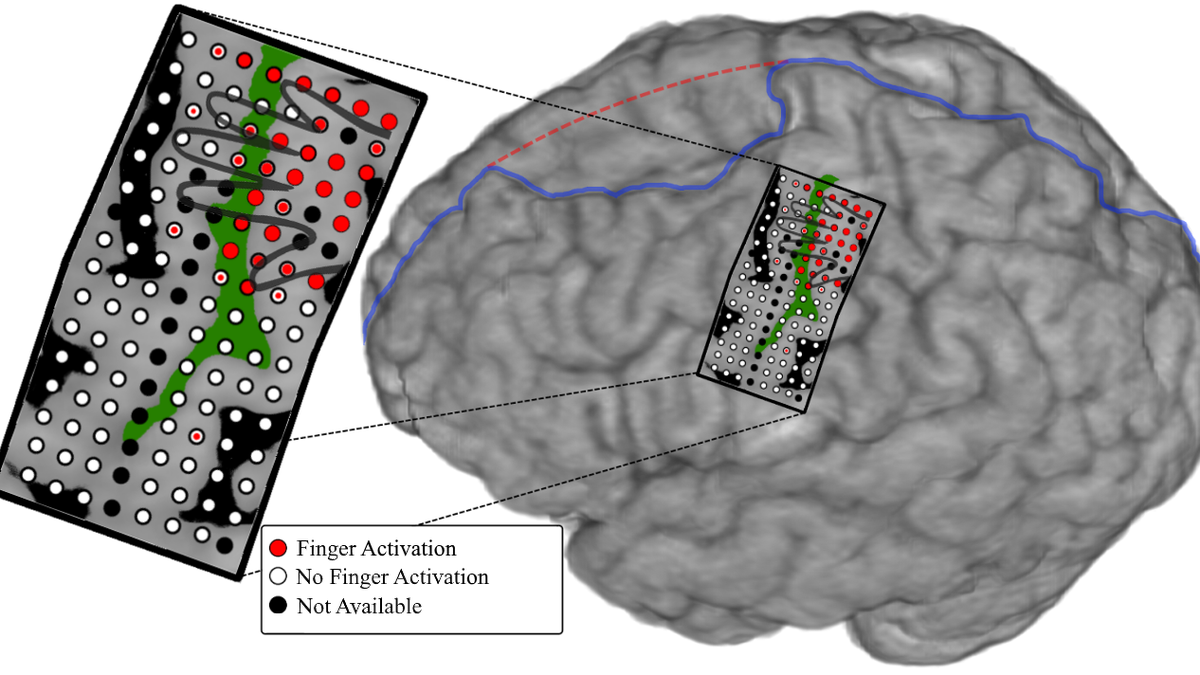

The study participant’s neurosurgeon implanted a rectangular sheet of film comparable to the size of a credit card on the part of the man’s brain connected with hand and arm movements. The Johns Hopkins team developed a computer program that recorded which parts of the brain were activated when each sensor detected an electrical signal. They also used a glove with buzzers in the fingertips to collect data on tactile sensation. According to the release, they measured the electrical activity in the brain for each finger connection.

After compiling the motor and sensory data, researchers programmed the arm to help the patient move individual fingers based on which part of his brain was active. They wired the arm to the patient through the electrodes, and they asked him to try moving individual digits. Study authors did not train the patient prior to the study, and the total experiment took less than two hours.

“The electrodes used to measure brain activity in this study gave us better resolution of a large region of cortex than anything we’ve used before, and allowed for more precise spatial mapping in the brain,” lead study author Guy Hotson, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins, said in the release. “This precision is what allowed us to separate the control of individual fingers.”

Researchers said the prosthetic first had a 76 percent accuracy, but when they combined the signals for the ring and pinkie fingers, that rate increased to 88 percent.

“The part of the brain that controls the pinkie and ring fingers overlaps, and most people move the two fingers together,” Crone said in the release. “It makes sense that coupling these two fingers improved the accuracy.”

Crone said further research involving mapping and computer programming would be needed before the technology could be successful for individuals missing limbs.