The pathogen has also been dubbed a cousin of HIV because of the similarities in the way it’s spread. (iStock)

It’s a virus that few people have heard of, but doctors around the world are urging the World Health Organization (WHO) to take action against it.

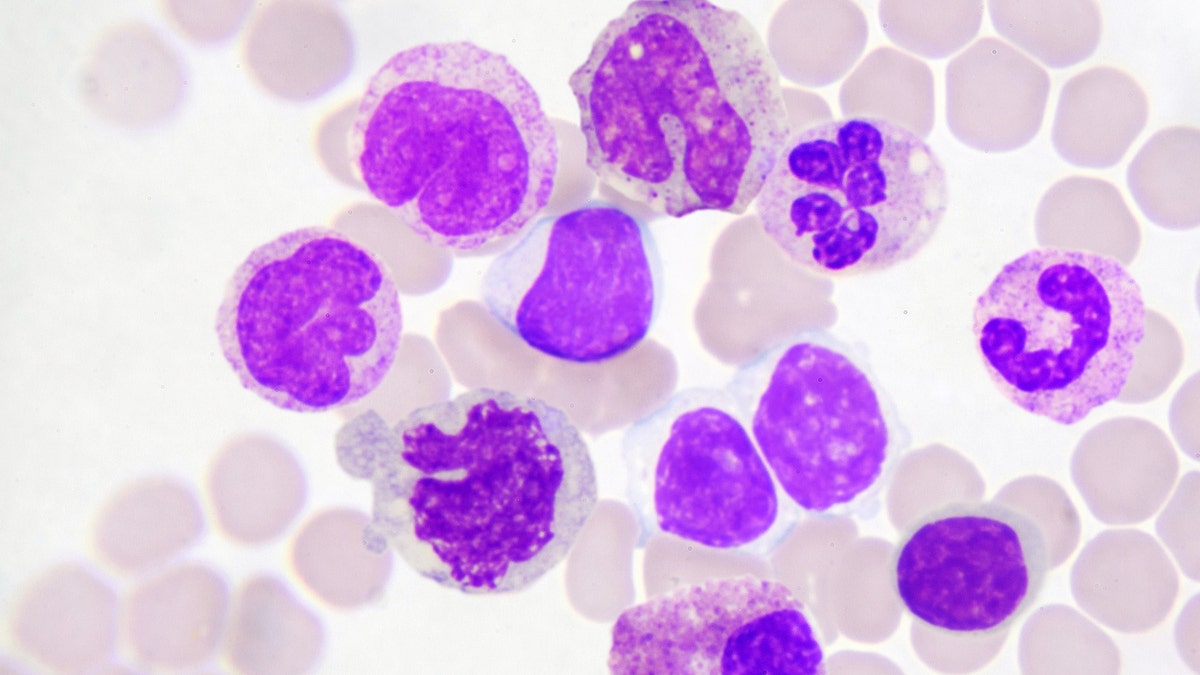

The virus in question is called HTLV-1, and in some cases, it can cause leukemia.

The pathogen has also been dubbed a cousin of HIV because of the similarities in the way it’s spread.

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) was first discovered in 1980, but it is believed the ancient virus was first present in nonhuman primates 40,000 to 60,000 years ago.

The virus does not negatively impact all carriers of the disease, but in some patients, it can cause spinal cord injury, inflammatory conditions, problems with mobility, and an aggressive form of leukemia.

“Ninety percent of the time, this will not trouble you, you will not be aware of it… But there’s another side of the coin, which is: Then why do we bother with it? Well… it does cause serious disease in the remaining ten percent, and it causes a very aggressive white blood cell cancer. It’s called adult T-cell leukemia,” Dr. Graham Taylor, professor of human retrovirology at Imperial College London, told Healthline.

“This is probably one of the most aggressive blood cancers, very difficult to treat, and with the best efforts… people still die. Fifty percent are dead within eight months. So that’s why we can’t ignore it,” he explained.

Taylor, along with 60 other co-signatories around the world, have written an open letter to WHO officials, urging them to “support the promotion of proven effective transmission prevention strategies against one of the most potent human carcinogens.”

HTLV-1 is spread in the same way as HIV.

It’s transmitted through bodily fluids from unprotected sexual intercourse, sharing of needles, breastfeeding, and through transfusions or transplants of infected blood or organs.

There is no cure and no vaccine against the virus.

“HTLV-1 is a virus that only obeys the laws of evolution and survival of the fittest. It will transmit efficiently where community practices provide an opportunity, and the virus over centuries will evolve to maximize its transmission efficiency during these opportunities,” Damian Purcell, PhD, the head of the molecular virology laboratory at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity at The University of Melbourne, told Healthline.

The spread in Australia

In Australia, where Purcell is based, HTLV-1 has reached what has been described as “hyperendemic numbers” among Australia’s indigenous population in the central part of the country.

In some aboriginal communities, 45 percent of adults live with HTLV-1. That’s an estimated 5,000 infected people in some of Australia’s most remote communities.

The virus is also prevalent in Brazil, the Central African Republic, Gabon, Iran, Jamaica, Nigeria, Romania, and Japan.

In Australia, a large number of indigenous communities have never been tested. The situation is complicated by healthcare access as well as cultural practices.

“The story of HTLV-1 in Australia has been complicated by the extreme remoteness of many of the newly identified high-prevalence communities, and in the early investigations, the lack of ethical consent given in primary language to test samples for HTLV-1,” Purcell said.

“The Australian experience tells us that HTLV-1 infections can become highly entrenched in communities that have preserved practices that allow an opportunity for HTLV-1 transmission,” he added. “It can be difficult to identify and modify these practices, especially when they occur in communities where they contribute to cultural identity.”

The global effects

But it’s not just Australia’s indigenous populations who are affected by HTLV-1.

The effects and social consequences of the virus are being felt all over the world.

“As a stigmatizing sexually transmitted disease, it divides communities just like HIV. It is heart breaking really,” Dr. Fabiola Aghakhani Zandjani-Martin, a sexual health, HIV, and HTLV-1 physician and scientist at The University of Queensland, told Healthline.

“Worldwide, it is mostly middle-aged women who are diagnosed with HTLV-1 diseases, and when they find out, their world falls apart. They have to ask themselves: How did I catch it? From my husband through sex, from my mother through breast milk? And then they need to consider having their children and grandchildren tested and examined.”

“It is really difficult,” she added. “That is why healthcare providers need to learn how to provide a sensitive and nonjudgmental care while being informed about the latest advances in HTLV-1 medicine. It is a tough job for the clinician and an even tougher situation for the patient.”

Taylor says 90 percent of patients don’t even know they have the virus, so they unknowingly pass it on to others.

In many countries, there are no programs available to test for HTLV-1, meaning there is likely a higher number of infected patients around the world than is currently known.

“You’ve kind of got a vicious circle; if nobody has heard about HTLV-1, then they’re not going to make a diagnosis of HTLV-1,” Taylor said. “So you then don’t see that there are people in your hospital, in your city, in your country who are HTLV-1-infected and developing disease.”

But Taylor is hopeful steps will be taken to prevent the transmission of HTLV-1, starting with WHO officials recognizing it as a rare or neglected disease.

“The huge strides we’ve made with HIV show just how much can be done with a problem that was appalling. Sitting there right beside it, discovered three years earlier, is HTLV-1, where you almost feel we’re no further on than back in the years immediately following its discovery,” he said.