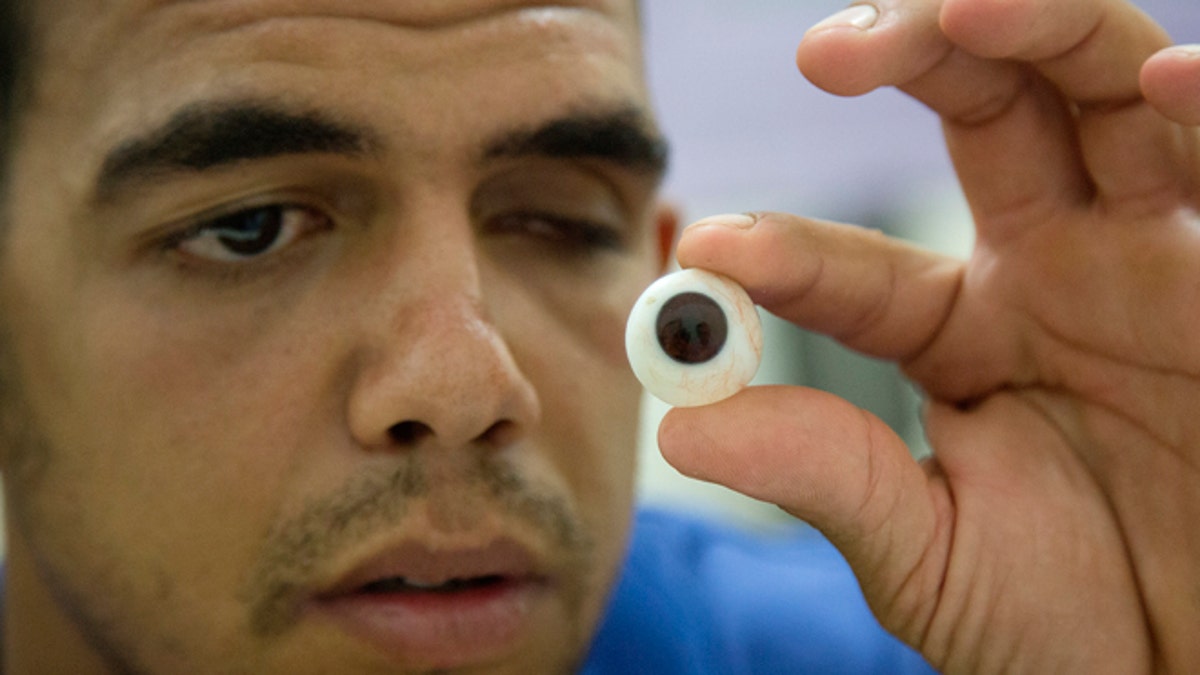

Oct. 6, 2015: In this photo, Mohammed el-Eshra, who lost his left eye in an accident when he was child, looks at artificial eye at Al-Radwan Clinic in Gaza City. (AP)

GAZA CITY, Gaza Strip – Imad Abu Wadi barely slept after losing his right eye during the summer 2014 war between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

The 26-year-old, then engaged, was waiting eagerly for his wedding. But with a red, hollow eyeless socket, he imprisoned himself at home.

"I was really suffering. I didn't go out to avoid running into someone who might say something to me," Abu Wadi said.

A year after the injury caused by an airstrike near his home, Abu Wadi is now married and feeling confident, thanks to an artificial eye he received two weeks before the wedding.

The ocular prosthesis was designed and made by Al-Radwan medical center, which is run by the Gaza-based charity Merciful Hands. The group, which is not connected to a British charity with the same name, receives funding from Muslim countries that include Turkey, Jordan, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Gulf Arab states.

Established in 2013, the center assists those who lost an eye to illness, congenital defects or injury, including in conflicts.

Yousef Hussein, an ocularist at Al-Radwan, says the center is the first in Gaza to design and fit artificial eyes. Prosthetic eyes used to be imported ready-made, which in many cases caused unwanted excretions in the eye socket.

"I felt people are very interested in this issue, including old people, and even more among married women or girls," said Hussein, who was an optometrist before completing a 10-month course in prosthetics in Jordan.

Designing and installing a prosthetic eye costs between $1,000 and $1,500. In Gaza's poor economy, these sums are not within everyone's reach.

But help is often available. As a war casualty, Abu Wadi got the costs covered by the Health Ministry. Various local and foreign donors, including Islamic charities from Gulf states and Europe, cover the costs for those unable to pay.

Since 2013, Hussein said he has fitted eyes for about 150 Palestinians, 45 percent of whom were injured by Israeli fire. Most of the rest were covered by donors and a few paid out of their own pockets.

Majed Abu Ramadan, president of the Palestinian Ophthalmological Society, says thousands of Gazans need prosthetic eyes. He said it is especially important to have the service available locally because the prosthesis often needs to be changed as the body grows.

Abu Wadi visited the clinic on a recent afternoon for a regular checkup. The ocularist, took out the new eye and examined it, holding it carefully between his thumb and index finger as the newlywed lay on the bed in the small room.

Abu Wadi then stood to pose in front of one of the many before-and-after photos that hang on the wall. When he took off his sunglasses, the artificial eye glittered slightly.

"I now look good," he beamed.

Hussein said they create the artificial eyes from acrylic plastic, which gives a normal look to the eye and decreases discharges. Most of the materials are available in Gaza, but he said the central circle that makes the artificial iris is sometimes delayed as it is imported through Israel.

Several patients sat in the waiting room. Among them was 17-year-old Yara Fatayer, accompanied by her mother.

A rock thrown by a boy hit her when she was 2 years old, costing her left eye. Her family took her to hospitals in Jerusalem and Egypt for an artificial eye, but gave up after realizing they needed to replace it often because she was growing so quickly at that age.

The high school student normally wears sunglasses to hide her injury. When her prosthetic eye is ready and fitted, "the first thing I will do is to remove the glasses, go out like any girl and do everything I could not do," she said.