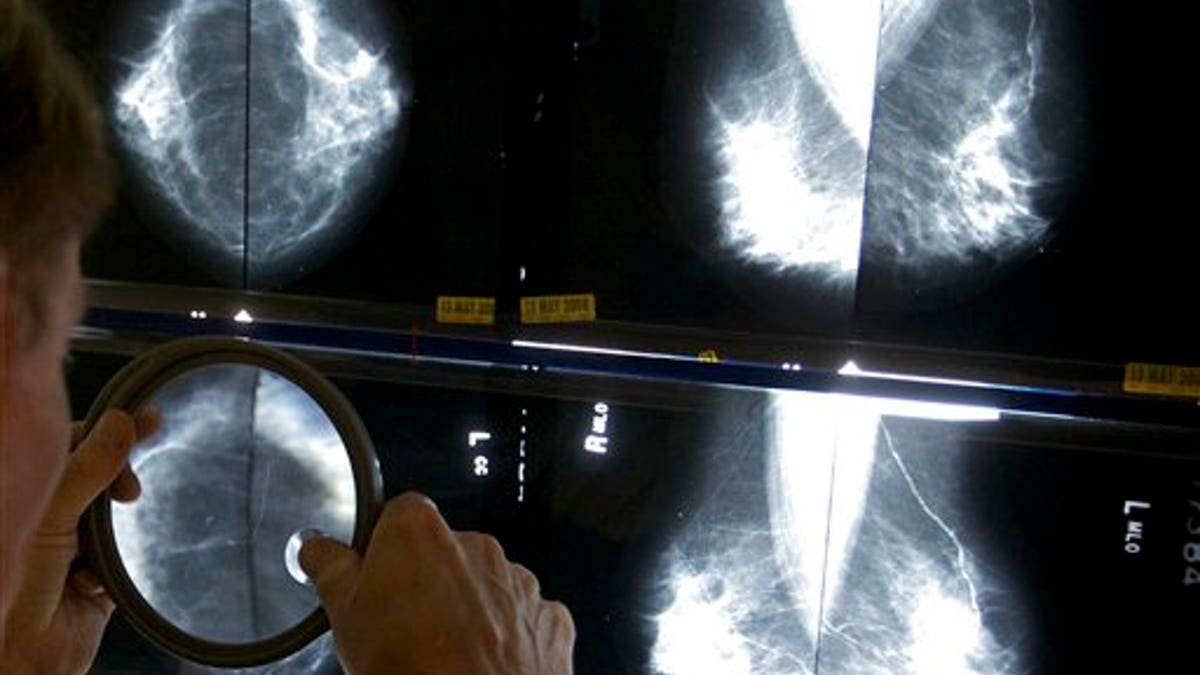

FILE - In this May 6, 2010 file photo, a radiologist uses a magnifying glass to check mammograms for breast cancer in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)

Years of schooling and training are needed to teach pathologists and radiologists to spot cancer on medical images, but a new study finds that pigeons can be about as accurate as these professionals, with the help of a few food pellets.

People don't have to worry about bird brains diagnosing their cancers any time soon, but the study's lead researcher says pigeons may have a future standing in for pathologists and radiologists in the kinds of mind-numbing studies of new technologies that involve examining thousands of images.

"If you showed me 10 images, I'd be ok," said Dr. Richard Levenson, of the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento. "But if you showed me 10,000 images, I would get irritated. Birds don't have the luxury to be irritated."

Levenson thought of experimenting with birds when he heard about work by Edward Wasserman of the University of Iowa in Iowa City and colleagues that found pigeons' visual recall is similar to that of humans.

Visual recall is needed for pathologists and radiologists to determine what is and is not cancer when looking at images.

Levenson teamed up with Wasserman for the new study, which put pigeons through three sets of tests. Each experiment showed the birds a different type of image: actual breast tissue samples with and without cancerous masses, mammogram (X-ray) images with and without small calcifications and mammograms with benign or cancerous masses.

The birds were taught to spot cancer and potentially cancer-linked calcifications over several days by being rewarded with a pellet of food each time one selected the correct button indicating the image was cancer free or had a malignancy.

To make sure the birds were not simply memorizing which images were cancerous and not cancerous, the researchers also showed the pigeons new images.

Among the images of actual tissue samples, the birds' accuracy rose from 50 percent (equivalent to chance) to about 85 percent 15 days later. They performed just as well when they were shown new images.

When the pigeons were taken as a group, and the choices of the majority tallied for each test, the birds demonstrated 99 percent accuracy in identifying cancer in the tissue sample images.

"They turned out to be extremely good pathologists," Levenson said.

Similarly, the birds' accuracy on images showing calcifications on mammograms ranged from 72 to 84 percent by the end of training. The pigeons were unable to differentiate between cancer and benign masses on mammograms, however.

The researchers write in PLOS ONE that they also found that the birds' accuracy varied when viewing images of tissue samples if the color and brightness were changed.

They suggest the birds may have a use in viewing many images as a cost-effective way to test the accuracy of new technology and new types of imagery. It's difficult and expensive to recruit human pathologists and radiologists to stare at huge numbers of images to help refine such technologies while they're in development, the authors write. The birds could do that job instead, they suggest.

"It seems reasonable that they would be good stand in and do some of that work for us," Levenson said.