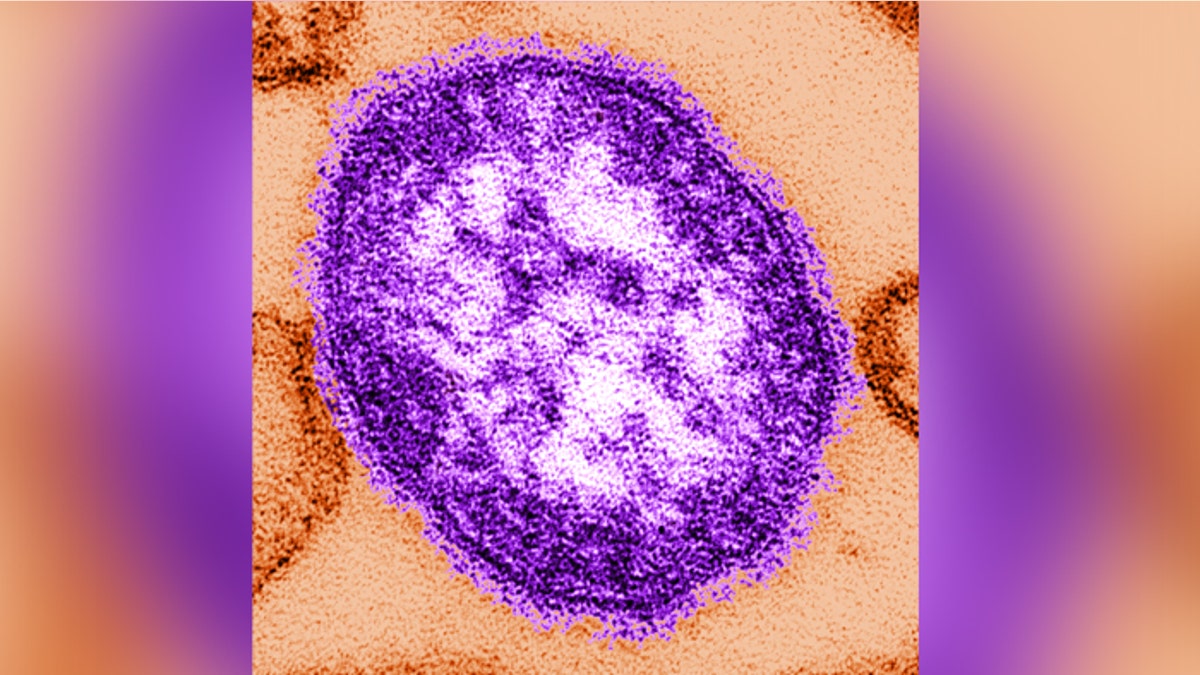

This thin-section transmission electron micrograph (TEM) reveals a single virus particle, or virion, of measles virus. (CDC.gov)

Measles – the virus once thought to be eradicated in many developed countries – is on the rise once again.

Although the MMR vaccine has significantly reduced measles cases around the world, many people still remain unvaccinated – leading to an increase of sporadic outbreaks of this highly infectious virus in densely populated areas.

In an attempt to help quell these measles surges, researchers from Georgia State University and the Paul-Ehrlich Institute in Langen, Germany have created an oral drug termed ERDRP-0519 that can block a measles-like virus in ferrets – preventing the disease from spreading to others.

According to the researchers, they hope to their drug will one day be used in combination with worldwide vaccination efforts, in order to eliminate the measles virus entirely.

“The vaccine campaign has made tremendous progress, and we firmly believe eradication must be centered on vaccination,” lead author Richard Plemper, a professor in the center for inflammation, immunity and infection at Georgia State, told FoxNews.com. “Our drug is not at all considered an alternative option, but we want to capitalize on a synergistic effect – to rapidly silence and eliminate local measles outbreaks in a population that overall has good vaccination coverage.”

Spread through the air by breathing, coughing, or sneezing, measles is an extremely contagious respiratory disease that causes a blotchy rash, high fever, and intense coughing. In fact, measles is so contagious that as many as 90 percent of unimmunized individuals who come into contact with the virus will become infected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As is the case with many viral infections, measles has an estimated two-week incubation period between the initial infection and the onset of symptoms. It is this silent window that researchers hope to target with their drug.

“When symptoms develop…the virus is already controlled by the immune response of the host. Many of these symptoms are the consequence of the immune system fighting the infection,” Plemper said. “At the peak of symptoms, the virus load in the patient is already in a rapid decline, because the immune system actively fights the virus. So it’s too late to come in with an anti-viral.”

The newly developed ERDRP-0519 drug works by targeting and inhibiting the viral RNA polymerase – an enzyme the measles virus needs to replicate and grow. By blocking this enzyme, the drug cannot synthesize new proteins and stops spreading throughout the body.

In order to determine the drug’s efficacy, Plemper and his colleagues administered ERDRP-0519 to a number of ferrets that had been infected with the canine distemper virus (CDV) – a lethal disease that mimics the measles virus in animals. When the researchers gave the ferrets their drug three days after infection, all the animals survived and the virus was completely suppressed.

“The ferrets also developed immunity,” Plemper explained. “So the surviving animals had protecting antibodies against the virus. When we went back later and re-injected them with the virus, they had immunity and did not develop symptoms.”

Plemper noted he is hopeful ERDRP-0519 will show no toxicity in humans and will one day be available as an oral drug, making it much more cost-effective than an injection.

Ideally, the researchers envision their drug as a tool to suppress outbreaks in already heavily vaccinated countries, as worldwide mobility and a recent rise in vaccine noncompliance have helped to foster intermittent measles infections in the United States and Western Europe. And although the fatality rate for measles is only 1 in 1,000 in developed nations, the complications associated with the disease can be quite severe.

“It’s not a disease one should take lightly,” Plemper said. “…The virus affects the immune system for a long time after infection is cleared. It’s the reason we see a large amount of bacterial super infections after measles is over. So we hope…not only to save patients from the acute disease but also these latent immune complications that follow infection.”

The research was published in the current issue of the journal Science Translational Medicine.