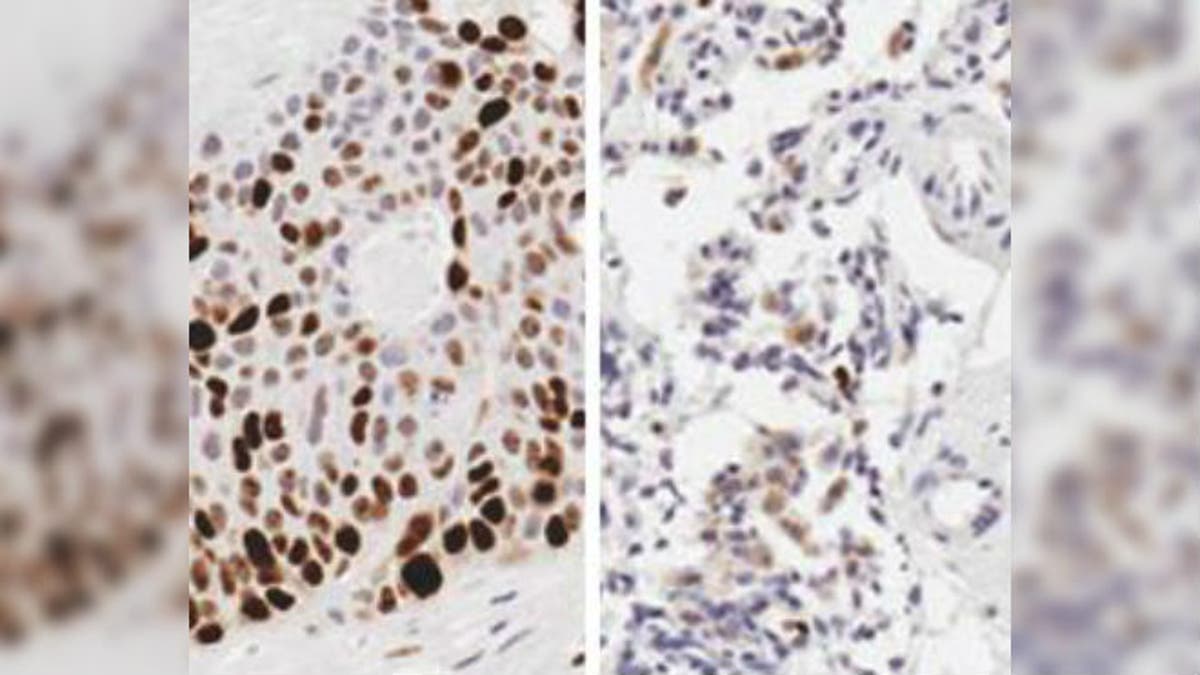

Compared to a control (left), mice treated with a chemotherapy drug using the device experienced significant growth reduction as confirmed by the lack of brown staining for a marker of tumor growth. Photo Credit: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Pancreatic cancer is known to be one of the most deadly forms of the disease, with a five-year survival rate of just 6 percent. Traditional treatment methods can be ineffective on pancreatic tumors, but researchers have developed a new device that delivers drugs directly to the cancer’s source, potentially increasing life expectancy for patients.

There are a number of reasons pancreatic cancer is notoriously difficult to treat. Most patients have no warning symptoms of the disease until the tumor is advanced. Also, most cases of pancreatic tumors are aggressive and spread quickly. When treated, drugs may be unable to effectively penetrate the tumor because of dense surrounding tissue and a lack of blood vessels.

A team of researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found by using electric fields, they were able to eliminate problems with dense surrounding tissue and drive chemotherapy drugs directly into the tumor, preventing growth and in some cases shrinking them. The device, called an implantable iontophoretic device, can be used either internally after a minimally invasive surgery by implanting the device's electrodes directly on a tumor, or externally to deliver drugs through the skin, which could be effective for more accessible tumors like inflammatory breast cancers and head and neck cancers.

Joe DeSimone, study author and chancellor's eminent professor of Chemistry at UNC, told FoxNews.com that in addition to penetrating the tumor more effectively, the device allows higher drug concentrations in tumor tissue while avoiding increased systemic toxicity.

“The device is able to deliver a much greater amount of drug into the tumor while reducing exposure of the drug to the rest of the body and therefore limiting the whole body toxicities and side effects,” DeSimone said. “It may also be used in conjunction with complementary drugs given to the entire body so that we can better target the tumor and any floating cancer cells in the body at the same time.”

The study, conducted in dogs and mice carrying human tumors, showed tumor shrinkage at what DeSimone called an “unprecedented rate”. Researchers expect the first human trials of the device to happen as early as next year.

DeSimone said the device opens the possibility of dramatically increasing the number of people who are eligible for life-saving surgeries.

“Surgery is the only way to cure this cancer, yet many patients cannot undergo surgery because the tumor is too advanced and may involve critical blood vessels,” he said. “The device could be implanted to initially shrink the tumors so that patients who couldn't get surgery would now be able to, and patients undergoing surgery may have better tumor clearance.”

DeSimone worked collaboratively with UNC School of Medicine colleagues, Dr. Jen Jen Yeh, associate professor of surgery and pharmacology and Dr. James Byrne of UNC Chapel Hill.

The findings are published in Science Translational Medicine.