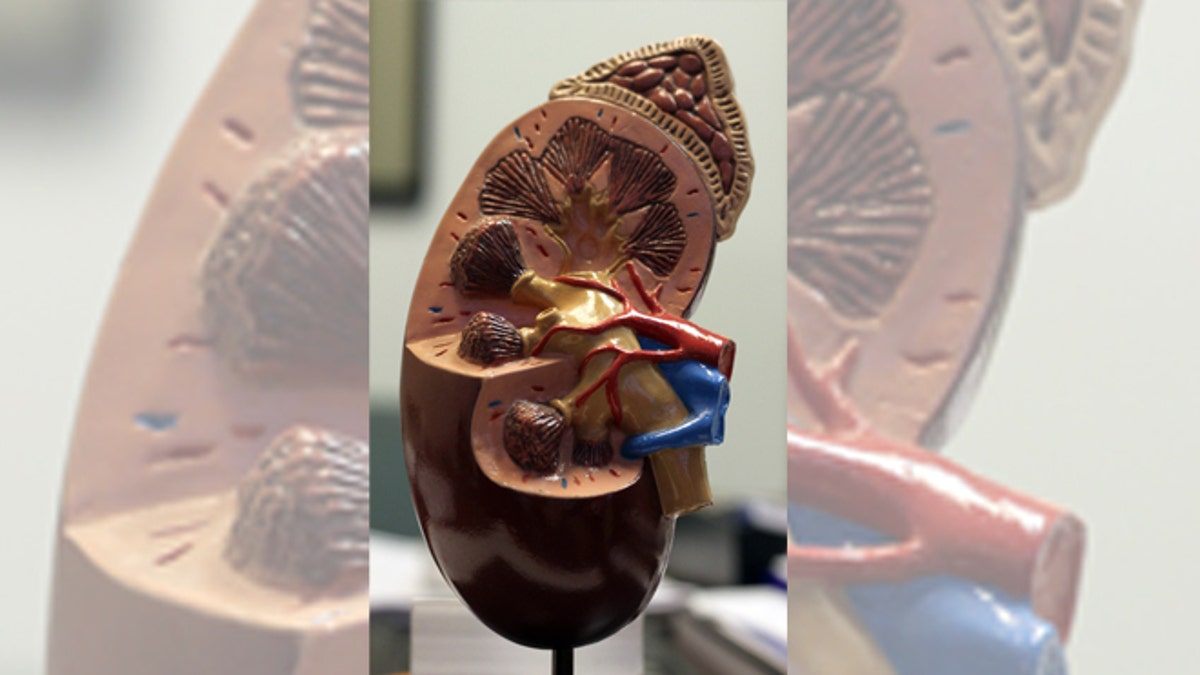

(Courtesy of the National Kidney Foundation)

Scientists have discovered yet another way to make a kidney - at least for a rat - that does everything a natural one does, researchers reported on Sunday, a step toward savings thousands of lives and making organ donations obsolete.

The latest lab-made kidney sets up a horse race in the booming field of regenerative medicine, which aims to produce replacement organs and other body parts.

Several labs are competing to develop the most efficient method to produce the most functional organs through such futuristic techniques as 3D printing, which has already yielded a lab-made kidney that works in lab rodents, or through a "bioreactor" that slowly infuses cells onto the rudimentary scaffold of a kidney, as in the latest study.

The goal of both approaches is to help people with kidney failure. In the United States, 100,000 people with end-stage renal disease are on waiting lists for a donor kidney, but 5,000 to 10,000 die each year before they reach the top of the transplant list.

Even the 18,000 U.S. patients each year who do get a kidney transplant are not out of the woods. In about 40 percent the organ fails within 10 years, often fatally.

If what succeeded in rats "can be scaled to human-sized grafts," then patients waiting for donor kidneys "could theoretically receive new organs derived from their own cells," said Dr. Harald Ott, of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. He led the research reported on Sunday in the online edition of Nature Medicine.

That would minimize the risk of rejection and make more organs available.

Ott's group used an actual kidney as its raw material, but competing labs are using 3D bioprinters to create the starting material, the scaffold or framework of the organ.

"With a 3D bioprinter, you wouldn't require donor organs," said Dr. Anthony Atala, director of the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at Wake Forest School of Medicine in North Carolina and a pioneer in that technology.

"The printer also lets you be very precise in where the cells go" on and in the scaffold. But he hailed the Massachusetts General Hospital work as "one more study that confirms these technologies are possible."

'BIOENGINEERED'

Ott and his team started with kidneys from 68 rats and used detergent to remove the actual cells. That left behind a "renal scaffold," a three-dimensional framework made of the fibrous protein collagen, complete with all of a kidney's functional plumbing, from filter to ureter.

The scientists then seeded that scaffold with renal cells from newborn rats and blood-vessel-lining cells from human donors. To make sure each kind of cell went to the right spot, they infused the vascular cells through the kidney's artery - part of the scaffold - and the renal cells through the ureter.

Three to five days later, the scientists had their "bioengineered" kidneys.

When the organs were placed in a dialysis-like device that passed blood through them, they filtered waste and produced urine.

But the true test came when the scientists transplanted the kidneys into rats from which one kidney had been removed. Although not as effective as real kidneys, the lab-made ones did pretty well, Ott and his colleagues reported.

Ott said he thinks using different kinds of cells to build up a kidney on the scaffold could work even better, since the immaturity of the renal cells they used might have kept the lab-made transplant from performing as well as nature's.

If the technology is ever ready to make kidneys for people, the cells would come from the intended recipient, which would minimize the risk of organ rejection and reduce the need for lifelong immune suppression to prevent that.

Although the technique requires human kidneys to provide the scaffold, the organs do not have to be in as good working order as those for transplant.

"That gives you the potential to make use of kidneys offered for transplant that would otherwise be discarded," said Atala, perhaps because they have a viral infection or other disease.

Atala himself is nevertheless forging ahead with 3D printing. He and his colleagues have used that technique to make not only kidneys but also mini-livers which, implanted in lab rodents, made urea and metabolized drugs like a natural one.

They are now trying the more difficult feat of making larger, pig-sized kidneys, as a stepping-stone to human kidneys.