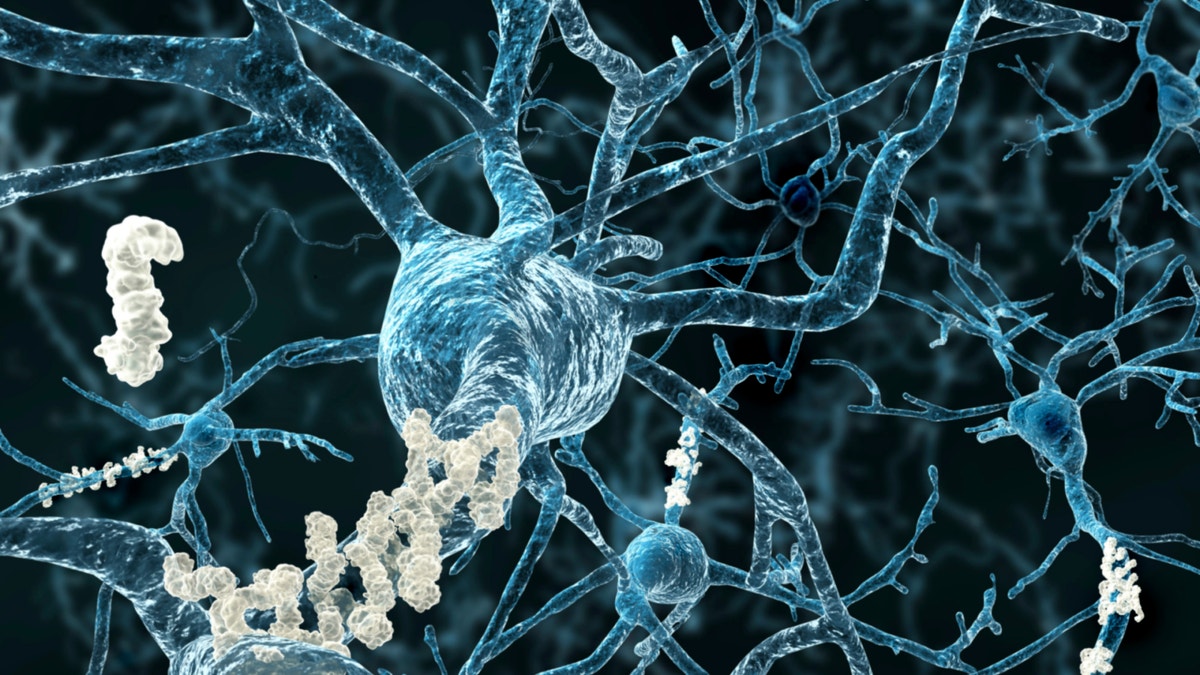

Amyloid plaques are pictured on neurons. (iStock)

Researchers have found that amyloid beta, the hallmark brain protein for dementia, may accumulate as a response to infection— which suggests Alzheimer’s disease may be caused by the body’s overreaction to certain bacterial threats.

Scientists say their observations, published Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine, could reframe the field’s perspective on the protein as well as impact medication development for the incurable disease, for which scientists do not know the cause.

Scientific American reported that, historically, researchers have believed amyloid beta serves no purpose except to wreak havoc on synapses in the brain when the protein is not cleared properly. When amyloid beta accumulates, cognitive decline and memory loss ensue, leading to Alzheimer’s.

But researchers at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital have observed in preliminary trials that the protein, while linked with dementia, may also play a sophisticated role in eradicating harmful microbes and alerting other cells of their invasion.

In their study, cultured human and hamster cells that were infected with the fungus Candida albicans and had a high expression of amyloid beta doubled the number of cells that weren’t infected, Scientific American reported. They saw that beta amyloid had a similar protective effect in roundworms, or nematodes, which usually die within two to three days after fungal infection. Those worms that overexpressed amyloid beta continued to live five to six days after infection. Also, mice genetically engineered to overproduce human amyloid beta lived about twice as long as mice without the protein, Scientific American reported.

When researchers injected a Salmonella bacterium into the brains of mice with Alzheimer’s, amyloid beta began to cluster around the bacteria in a mere 48 hours, and act like known antimicrobial peptides to prevent infection.

“We didn’t know this was even possible— that amyloid plaques would form rapidly overnight,” study author Rudolph Tanzi, the Joseph P. and Rose F. Kennedy Professor of Child Neurology and Mental Retardation at Harvard University, told Scientific American. “And in the middle of each plaque was one Salmonella bacterium, supporting the theory that the amyloid deposition had formed around the microbe as an entrapment mechanism— just like LL37 and other established antimicrobial proteins.”

That the buildup of amyloid beta may be spurred by an overreaction to infection aligns with what scientists already know about the aging body— that, as people get older, their function of the blood-brain barrier and immune system begin to wane. Tanzi told Scientific American that even a few pathogens could offset the accumulation of this plaque, “and that could rapidly start the cascade toward the disease, causing tangles and inflammation.”

“You’ve got all three pillars of Alzheimer’s right there,” he told Scientific American.

Next, Tanzi and his team plan to further examine pathogens that may play a role in Alzheimer’s and other diseases, like diabetes, that are associated with amyloid plaques.