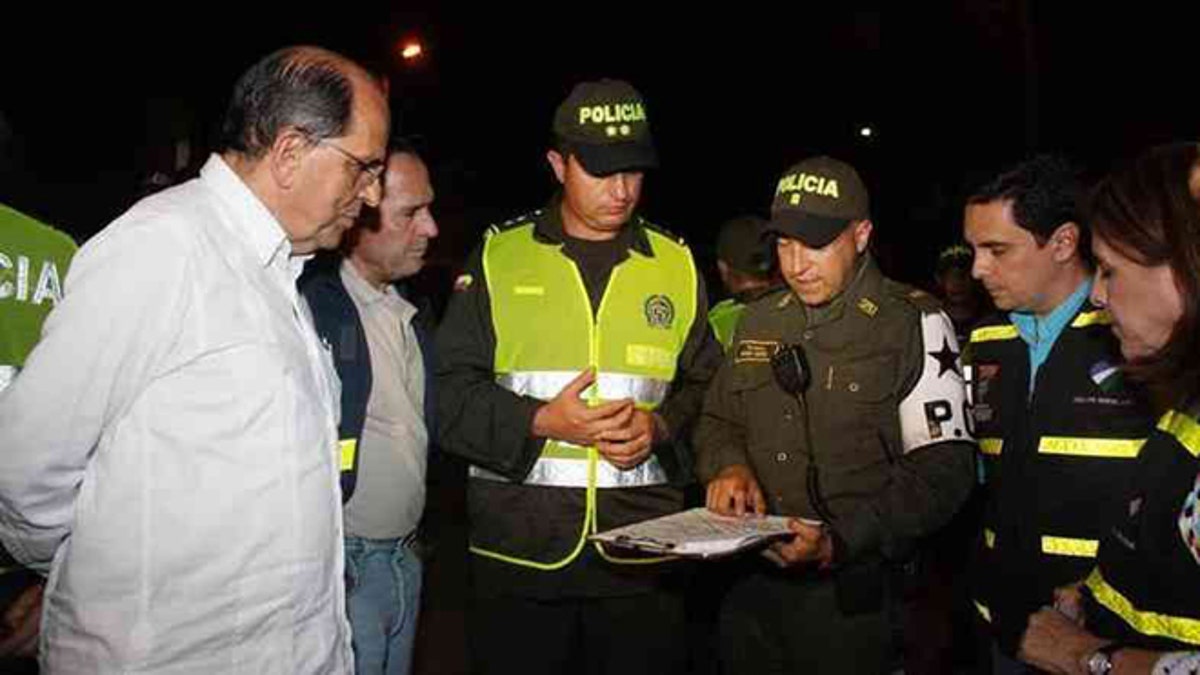

Cali Mayor Rodrigo Guerrero meets with police. (Prensa Alcaldía de Calí)

What does an epidemiologist – someone who studies the patterns of health and disease conditions – know about fighting crime?

If that epidemiologist happens to be Rodrigo Guerrero, the current mayor of the Colombian city of Cali, the answer is apparently a lot.

The Harvard-trained scientist, on his second, non-consecutive term as the mayor of Colombia’s third largest city, was recently awarded the first ever Roux Prize – given to individuals who use scientific data to improve public health – for his work in reducing violent crime and homicides in Cali.

“What Dr. Guerrero has done to drive down violence using a public health approach is extraordinary,” Rafael Lozano, Director of Latin American and Caribbean Initiatives at Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) said in a press release. “This is a powerful illustration of how Global Burden of Disease data can influence policy at the regional level.”

Guerrero was first elected to the mayoral post in 1992, when Cali – and Colombia as a whole – was in the midst of one of its bloodiest periods thanks to widespread drug violence and brutal clashes between the military and left-wing guerrillas. Upon taking office, Guerrero began to study data on the number and nature of violent incidents in the city – which at the time had a homicide rate of 100 per 100,000 people. He held meetings with law enforcement officials, and came to the realization that drug traffickers were not the only culprits of the violence.

The data suggested that most of the violence occurred on the weekends or during holidays, with one-quarter of all homicide victims being intoxicated and 80 percent dying from wounds suffered from gunshots.

“Among the many risk factors for urban violence identified in Colombia are: proliferation of firearms in the civil population; unrestricted alcohol consumption in public places; absence of cultural patterns to regulate urban behavior; inefficient and corrupt judicial and police systems; and the presence of organized crime,” Guerrero wrote in an editorial for the World Health Organization back in 2002.

He then created a violence-prevention program that among other things limited the number of hours that alcohol could be sold and worked with the Colombian army, the main gun vendor in the country, to issue gun bans during periods when the risk of homicide was highest.

The result was a 33 percent drop in homicides in Cali, and the program being picked up in other cities throughout the country such as the capital, Bogotá, and Medellín.

“What Guerrero did was show us that we not only have to look at the violence by drug traffickers and war but at domestic violence and the violence that is integrated into the culture,” June Carolyn Erlick, the editor-in-chief of ReVista, the Harvard Review of Latin America told Fox News Latino.

After leaving office, Guerrero went on to hold positions at both the Pan-American Health Organization and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), where his techniques were implemented in 18 other countries throughout the region including in Chile, Peru, El Salvador, Brazil, Guatemala, Jamaica, Belize, Panama, Honduras, Nicaragua and Venezuela. In 2012, 15 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean committed to joining an IDB-funded partnership to share and standardize data on crime and violence under the leadership of the Universidad del Valle in Colombia.

Guerrero’s epidemiological approach has worked throughout his country, and experts say that his technique can used in any urban area around the world.

“In any large city this would be absolutely implementable,” Erlick told FNL. “Look at Los Angeles, New York City or São Paulo. The value provided by the program can be easily seen.”

The program, however, has to be kept up or cities reverse back into violence, history suggests.

While Guerrero was away, Cali’s murder rate began to rise as the diligent tactics employed under his guidance were cast aside.

After retaking office a full 20 years after his first term, Guerrero began to reinstitute his violence-reduction program and promised to reduce murder to 60 per 100,000 – a goal that has already been accomplished after only two years.

“I am a pathological optimist,” Guerrero said. “My reference figure is Galileo, who said, ‘we should measure what is measurable and make measurable what is not so.’ Personally, I believe that measuring is the key of the scientific method, so I am all for indicators, location, coverage, quality, results.”