Veterans with PTSD cope with holiday fireworks

Fourth of July fireworks bring undue stress to nation’s veterans living with PTSD

LAS VEGAS – Americans will celebrate the nation’s 242nd birthday with July 4 trips to the beach, with barbecues and with celebratory fireworks.

The rockets’ red glare is an Independence Day tradition. But for the men and women of the U.S. armed forces, the jarring noises can trigger symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

Whether it’s a Roman candle, a traditional firecracker or small poppers, the sounds transport service men and women to the battlefield, conjuring up memories and images most have tried to forget.

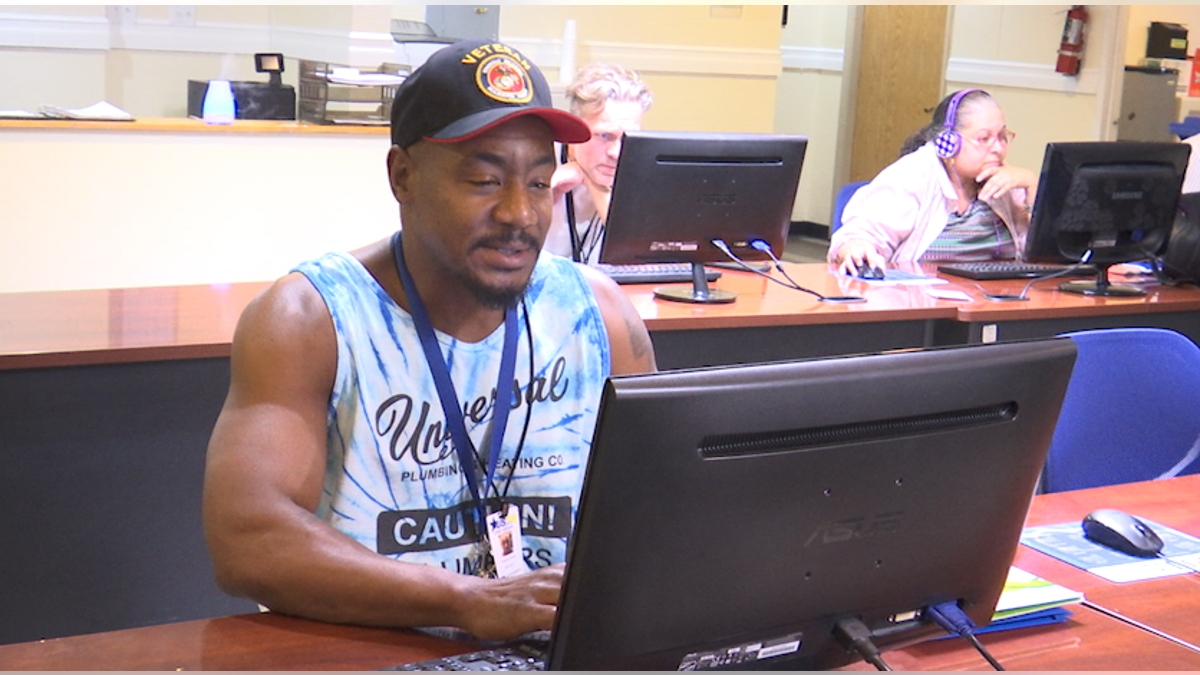

“It depends on the state of mind I’m in. For some veterans it can be disturbing, it can make you angry,” said Benjamin Dupree, who served in the U.S. Marine Corps during Operation Desert Storm.

For others, it takes them back to specific areas of combat.

“For me it’s the explosion…In my case, it puts you right back, especially if it’s unexpected …bang! ... you jump, you duck…it’s what you were trained to do," says John Ferron, who served during the Vietnam War in the Navy.

There is something the public can do. A nonprofit charity called “Military with PTSD” sells yard signs to veterans to put in their front lawn. In large print they say,” VETERAN LIVES HERE…PLEASE BE COURTEOUS WITH FIREWORKS.” It’s a way for civilians to be mindful if they have a veteran living next door.

A yard sign veterans can purchase from the nonprofit charity "Military with PTSD" that lets their neighbors know to be mindful of setting of fireworks during Fourth of July (Military with PTSD)

“The reaction is very real to them at that moment. And so they get very embarrassed because here they’re supposed to be these hardened warriors and a firework goes off that they’re not expecting. It’s always the unexpected fireworks. They always do fine at big firework shows, they can go and participate. A lot of veterans can set off their own fireworks and they’re fine, but when they’re not expecting them on the days leading up to and around Fourth of July, that’s where the problems come in," says Shawn Gourley, executive director of “Military with PTSD.”

In one tragic instance in 2015 in Georgia, a 27-year-old Army veteran committed suicide after going into a PTSD attack from an exploded firework on Fourth of July.

The number of veterans living with PTSD is growing, but experts say many cases still go undiagnosed or unreported.

“PTSD has increasingly been studied mostly related to war…The reliving of that trauma is so much more…we used to be able to come back from war and not be able to see it over and over again…even if you’re not at war you’re watching it happen somewhere else [on television],” says Sanam Hafeez, a Columbia University neuro-psychologist.

Hafeez says veterans often self-medicate to deal with the prolonged effects and symptoms.

“There’s a certain integrity and toughness for war veterans…they like to say I’m tough and I defended our country. I’m this person who should be able to manage this and take care of this.”

Benjamin Dupree sits at a veterans career services center in Las Vegas. He served in the U.S. Marine Corps during Operation Desert Storm. (Fox News)

For those veterans coming back from our most recent foreign conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs says between 11 and 20 out of every 100 veterans have PTSD in a given year.

And as the celebrations go on among civilian life, psychiatrists in the medical community suggest that veterans listen to music to avoid the loud sounds of the fireworks, stay around comfortable crowds like family or friends or even isolating themselves in order to stave off sudden attacks.

Still, the pain of war never dissipates.

“The war is never over…because your mind always brings it back to your recollection,” says Ferron.