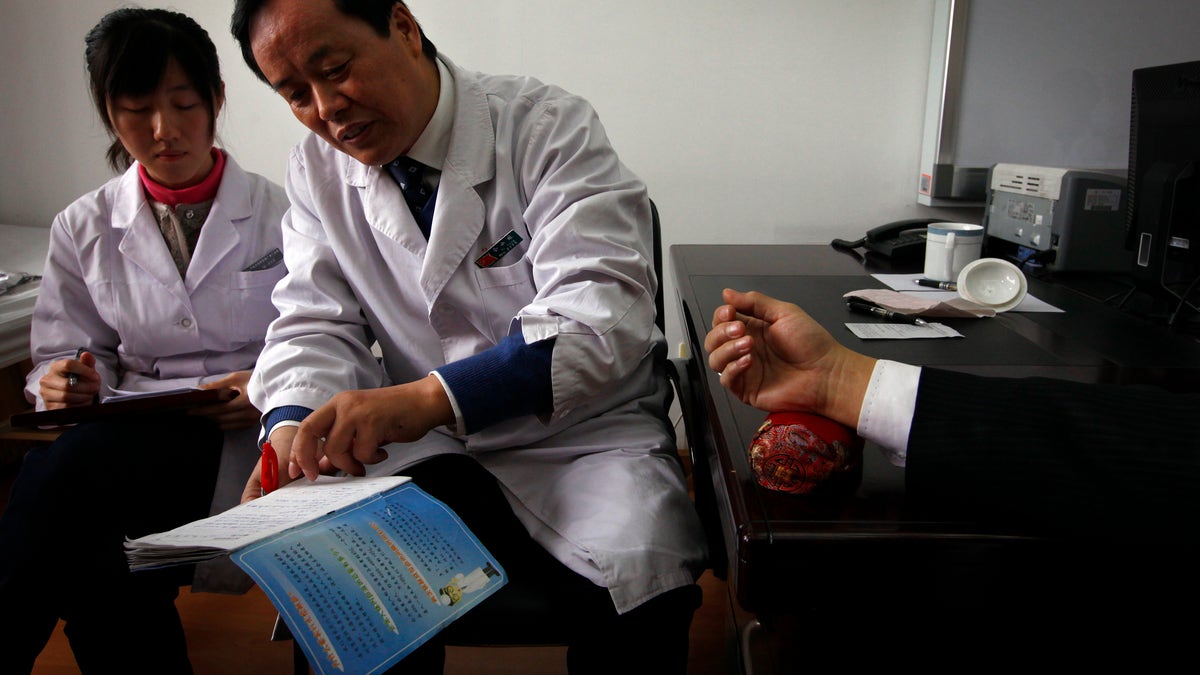

A diabetes patient rests his arm on a table for diabetes specialist Doctor Tong Xiao Lin (C) during a medical check-up at the Guanganmen Chinese medicine Hospital in Beijing March 19, 2012. REUTERS/David Gray

Rising diabetes rates among middle-aged and elderly adults in China may be tied to their exposure to famine early in life followed by a rapid surge in economic development, a recent study suggests.

China experienced a famine between 1959 and 1962. Then the country rebounded, with gross domestic product (GDP) - a widely accepted measure of economic health - surging from $28 per capita in 1978 to $6,803 in 2013.

Researchers analyzed data on about 6,900 adults, including roughly 3,800 who experienced famine followed by a different economic status in adulthood.

Compared with the group that didn't live through the famine, those exposed to famine in their mother's womb were 53 percent more likely to have diabetes as adults, the study found.

Exposure to famine during childhood was linked to an 82 percent increased risk for diabetes later in life.

In addition, Chinese adults living in more affluent areas had a 46 percent greater risk of diabetes than people living in poorer communities, the study found.

"We found that there was a significant association between diabetes and famine exposure in utero and during childhood; living in areas with high economic status in adulthood is further associated with an increased risk," said senior study author Yingli Lu of Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital and Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine.

"Subjects experiencing undernutrition followed by overnutrition may have the highest risk of diabetes," Lu said by email.

It's possible the link exists because people who are malnourished in utero or during childhood may have a reduced ability to convert sugars into energy later in life when they get the chance to eat much more food, Lu said.

Overall, roughly 11.4 percent of the adults in the study had diabetes, 31 percent were obese and 40 percent had high blood pressure.

The study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism doesn't prove that famine followed by economic boom times can cause diabetes, only that these things appear connected.

Shortcomings of the analysis include a lack of data on people who may have moved at different points in their lifetime to live in areas of varying levels of affluence, the researchers acknowledge. The precise start date of the famine is also unclear, the authors note.

How the famine ends may also influence diabetes risk later in life, Stefan Thurner, a researcher at the Medical University of Vienna who wasn't involved in the study, said by email.

"The hunger has to stop abruptly; if malnutrition continues after the baby is born the effect of developing diabetes is much less," Thurner said. He notes, for example, that diabetes didn't surge after the so-called Leningrad famine from 1941 to 1944 because hunger problems persisted for years after the end of the siege.

The findings add to a growing body of evidence supporting the focus on maternal and infant nutrition during famines and other situations when food may be scarce, said Dr. Mikael Norman, a researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm who wasn't involved in the study.

"Pregnant women and their newborn infants should have the highest priority to get nutritional relief," Norman said by email. Babies born too small, a risk of malnourished mothers, have an increased risk of diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity and cardiovascular disease, he noted.

Adults who survive childhood famine should also take care to adopt a lifestyle that may help minimize their risk of diabetes and other health problems that might be exacerbated by a sudden change in financial circumstances, Norman said.

"Sedentary lifestyle, fast food and smoking will add to the risk of having a cardiac event or diabetes," Norman said.