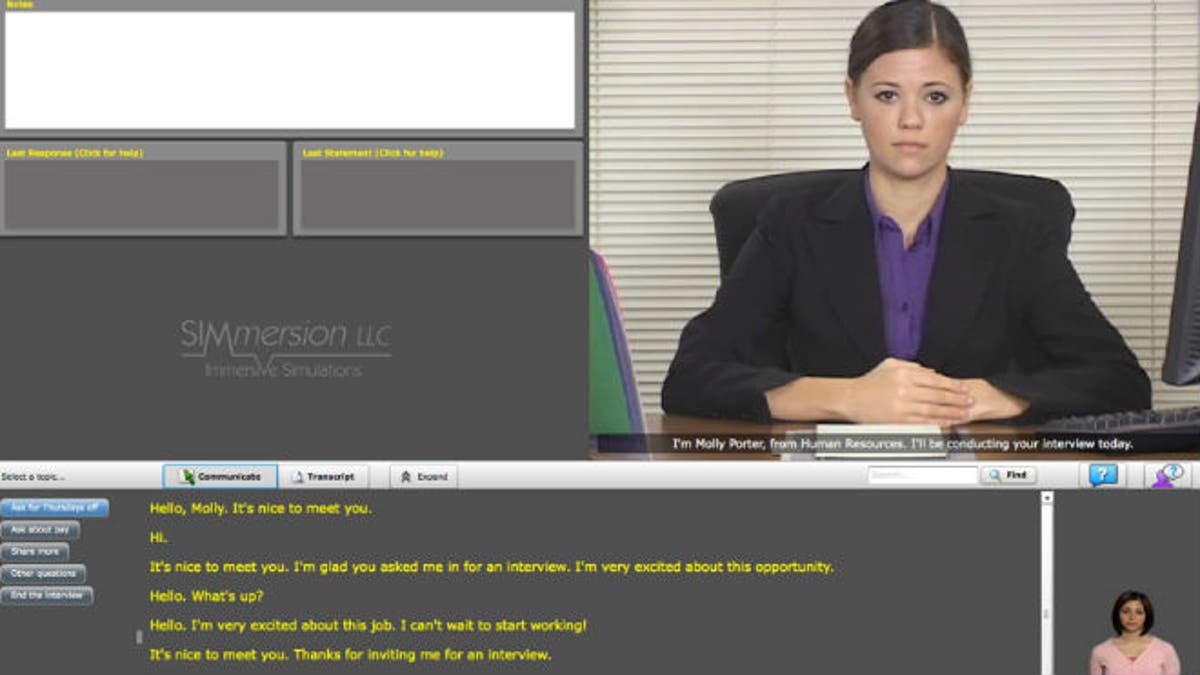

A screenshot of the 'Molly' training program used in the experiment, courtesy of the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Researchers at Northwestern Medicine have developed a training program to help autistic adults prepare for job interviews – based on software previously used to teach interrogation tactics to FBI agents.

About 1 in 68 children in the United States has been identified as having an autism spectrum disorder (ASD), according to recent data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). As these children become adults, finding employment may be a challenge; research shows that employment rates for individuals diagnosed with ASD ranges from just 25 to 50 percent.

“Individuals with ASD are characterized with having impairments in social communication and have difficulties picking up on social cues, or using empathy and these traits might lead to difficulties in job interview settings,” Matthew J. Smith, an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern, told FoxNews.com. “And [conversational simulation] training has been found to be effective in different areas, such as with FBI agents or training physicians to have difficult conversations with patients.”

Based on the software used to train FBI agents, Smith and his colleagues developed a more advanced virtual reality job interview training program, in which participants could interact with a virtual human resources representative named Molly Porter during a mock job interview.

“[Molly] leads the interview and asks trainees questions like, ‘If you could have changed one thing at your last job, what would it be?’” Smith said. “Trainees then have five to 15 response [options] that come on the screen that they can choose [a response] and speak it out loud so they can practice rehearsing.”

The participants are presented with a variety of potential answers to interview questions – ranging from strong answers to inappropriate ones. The program’s algorithm then scores the trainees, based on their responses. Users can then print a copy of their conversation, complete with color-coded feedback, so they can learn why the responses they chose were characterized as strong or weak.

Trainees also interact with different versions of Molly as they progress through the program – from the easiest level, Friendly Molly, to the hardest level, Curt Molly.

“A job interview is a stressful experience for just about anybody, and responding to job interview questions through repeated practice with simulation helps them learn what to say ahead of time and be more at ease when asked these questions in a real-life setting,” Smith said.

Using ‘Molly’ to succeed

In a study published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Smith and his colleagues tested ‘Molly’ on a group of 26 individuals with ASD, all of whom were actively searching for a job, as they were either unemployed or underemployed. Approximately half of the participants participated in up to 10 hours of training with Molly, while the others continued with their normal job search strategies.

At the beginning and end of the experiment, both groups underwent mock interviews with a professional actor playing a human resources representative. They were then evaluated on a scale of one to five, depending how well they met certain criteria, including: comfort level, ability to negotiate, appearing dependable and hardworking, appearing easy to work with, sharing information about themselves in a positive way, sounding honest, seeming interested in the position, acting professional and the overall feeling of rapport they were able to establish with the interviewer.

“What we found was that the group that worked with Molly significantly improved over time in their job interview role play performance, whereas the control group did not,” Smith said.

Overall, 90 percent of the group that trained with Molly reported that the program was fun, easy to use and helpful in preparing them for future interviews. One of the ways the trainees improved was in their ability to share information in a positive way during the interview process.

“For instance, when looking at young adults with ASD, many had never had a job before,” Smith said. “During the interview process, they had the option to say, ‘I’ve never had a job,’ or they can say, ‘This would be my first job, but I learn quickly and would be a reliable worker.’ Based on those two statements, you can tell one would be perceived more positively.”

The study participants also improved their ability to come across as a hard worker and as someone who would be easy to work with. Smith and his colleagues followed up with all of the participants six months after the experiment concluded – and were pleased with the initial outcomes.

“After a preliminary review of six-month follow-up data, we’re optimistic that this training may help people get jobs or other types of work,” Smith said.

Smith's software can also be used to help adults with psychiatric disorders through an interview process.

“Individuals with severe mental illness or psychiatric disability, some of the things they may need to learn how to talk about in a job interview include asking for accommodations, or being able to talk about how they’ve overcome some hardships in their life, and how that has helped them learn certain skills they can apply to a job setting,” Smith said.

Smith and his colleagues hope to continue to test the program in different settings and on different groups of individuals.