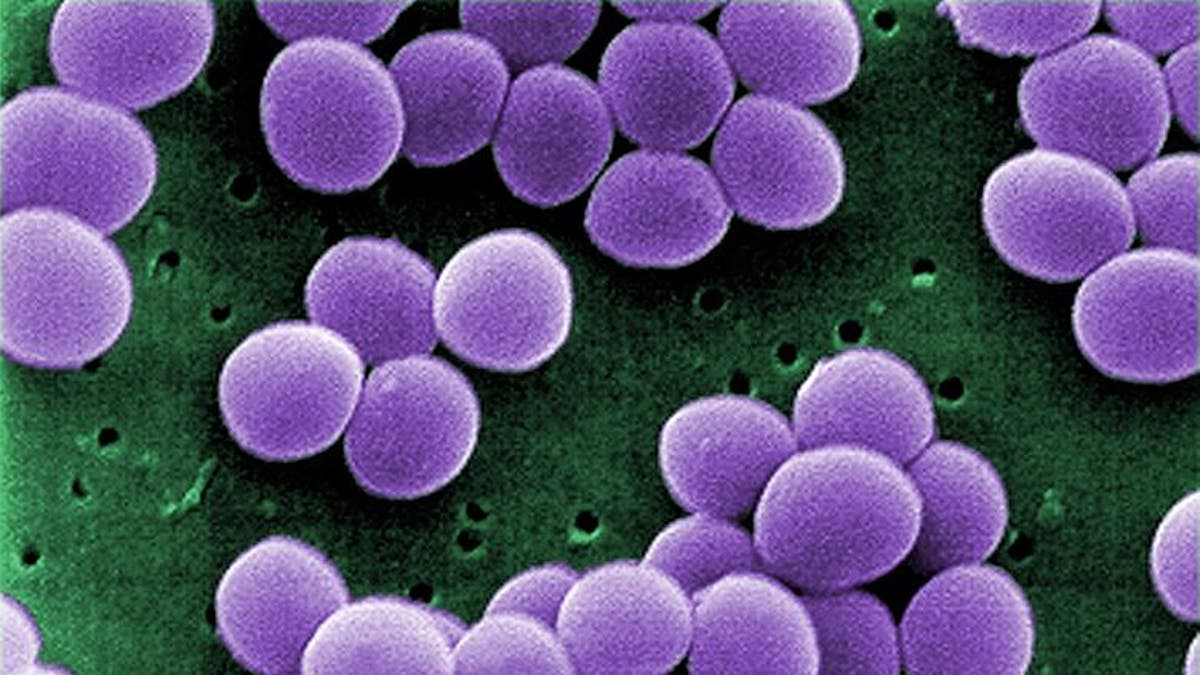

Chronic exposure to small amounts of staph bacteria could be a risk factor for lupus, according to new research.

In a recent study, Mayo Clinic researchers found that mice exposed to low doses of a protein found in Staphylococcus aureus developed a lupus-like disease, consisting of both kidney problems and autoantibodies like those found in the blood of lupus patients.

Lupus, an autoimmune disorder, occurs when the immune system begins attacking the body’s own tissues and joints.

Currently, there is no known cause of lupus. However, people who are genetically predisposed to the disease may develop it after exposure to environmental triggers – such as an infection, certain drugs or sunlight.

This latest study suggests the staph protein may be one of those potential triggers. Staph is commonly found on the skin or in the nose, and it is estimated that 20 to 30 percent of people are carriers of the bacteria.

Prior research has found that carrying staph may be linked to other autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis, Kawasaki disease and graulomatosis with polyangiitis.

"We think this protein could be an important clue to what may cause or exacerbate lupus in certain genetically predisposed patients," study co-author Dr. Vaidehi Chowdhary, a Mayo Clinic rheumatologist, said in a released statement.

According to Chowdhary, if the results hold true in humans, the next step would be to see whether eliminating staph on the body or developing an antibiotic against it could delay the onset of lupus in people who are genetically predisposed to the disease.

“A very interesting study found the blood can have lupus antibodies up to seven years before a diagnosis is made, so it’s hard to know when the disease actually starts and how you can prevent the onset,” Chowdhary told FoxNews.com. “If staph is shown as a risk factor, we want to investigate. If we eliminate the staph, do we delay or prevent lupus?”

In addition, Chowdhary said, the researchers would like to look at the rates of staph colonization in people who already have lupus. “Do they carry bacteria more than healthy people?” she said. “Does it correlate with the number of symptom flares?”

“[Symptom] flares are always a problem with lupus,” Chowdhary added. “It’s a possibility that the more the disease is active, the more likely it is to involve more organs. While this is quite hypothetical, it could be if flare rates are reduced, patients could have better outcomes.”

However, Chowdhary emphasized the importance of keeping the findings in perspective.

“Lupus is such a complex disease and there’s likely not just one single factor involved,” she explained. “There are several hurdles [to studying it]. It’s very rare, and there are different categories, but we tend to lump all patients together... The more we know, the better we can classify these patients.”

The study was published this month in the Journal of Immunology.