Doctors test stents that dissolve

Cardiac stents have been used for almost 20 years to clear blocked arteries but once the stent does its job a metal scaffold is left behind. A clinical trial is underway to test a new type of stent that is completely dissolvable

Nuri Ansari has a strong family history of heart disease, as seven of his siblings have undergone open heart surgery. A few years ago, he started to develop concerning symptoms himself.

"I was not breathing properly,” Ansari, who lives in New York City, told FoxNews.com. “I just had to catch my breath, I was tired if I walked up four flights of steps."

In order to avoid open-heart surgery, doctors placed three stents in his heart. Afterwards, Ansari experienced significant relief from his symptoms.

"I have a 6-year-old and so keeping up with him requires a lot of stamina and strength,” Ansari said. “ But I'm able to hang out, and I think I can get back to that just based on the way I feel."

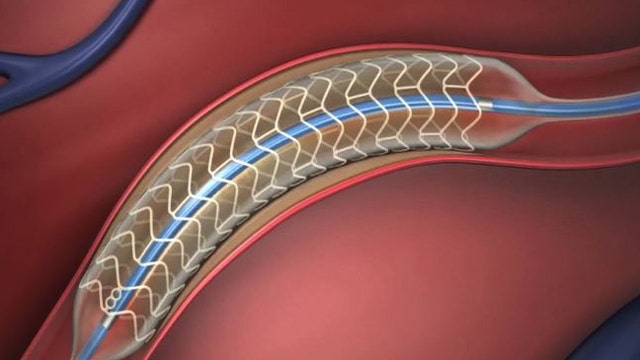

Doctors have been using stents to clear blocked arteries for the past 20 years. Stents are inserted into a person’s arteries using a catheter in order to keep the blocked artery open and improve blood flow. Some stents also give off medication to prevent plaque from re-forming in the arteries.

However, after the procedure, the metal scaffolding remains in a patient’s heart for life, sometimes leading to further health complications. If a patient stops taking their blood-thinning medication, it's possible for a blood clot to form inside the stent - a condition called stent thrombosis. Additionally, the stent prevents a person’s blood vessel from regaining its ability to react normally again after the procedure.

Now, clinical trials are underway to test a stent that dissolves after it finishes doing its job. The unique device called “Absorb” was created by Abbott Technologies and is being tested at 60 sites throughout the United States, including at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City.

"It starts dissolving in the body after about 12 months,” Dr. Annapoorna Kini, a cardiologist at Mount Sinai, said. “And it takes anywhere between two and three years for it to completely dissolve."

Researchers hope to enroll more than 1,000 patients in the single-blind study, meaning patients won’t know which type of stent they are receiving.

“It's a really important piece of clinical research so that we can keep it unbiased,” Dr. Roxana Mehran, an interventional cardiologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said. “So if there are no (symptoms, or) if there are less symptoms or less recurrence, we're not just really saying it's due to the fact that the patient knew they had something different."

While the dissolvable stents are placed in the same location as a traditional stent, it takes slightly longer to insert a dissolvable stent, because the device is less flexible.

The device is already being used in Europe and India, and doctors hope the technology will be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration within the next two to three years.

For more information, visit clinicaltrials.gov.