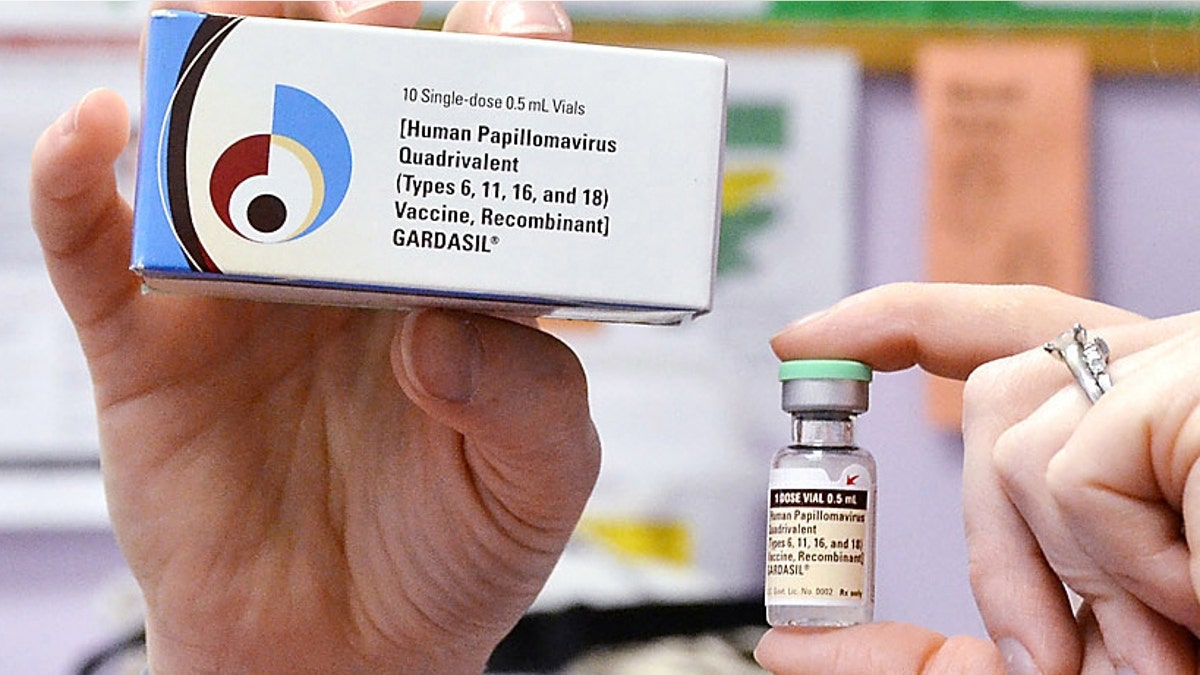

FILE - A child health nurse holds up a vial and box for the HPV vaccine, brand name Gardasil, at a clinic in Kinston, N.C. on Monday March 5, 2012. A vaccine against a cervical cancer virus has cut infections in teen girls by half, according to a study released Wednesday, June 19, 2013. The study confirms research done before the HPV vaccine came on the market in 2006. But this is the first evidence of how well it works now that it is in general use. (AP Photo/Daily Free Press, Charles Buchanan) (A2012)

Abnormal changes in the cervix that can lead to cancer are less frequent in young women since the introduction of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, a new study suggests.

But tests to look for these changes are also being done less often in women age 21 and younger, which could account for at least some of the decline in “cervical lesions,” the researchers point out.

“The decreases in high grade lesions are most likely due to a combination of decreased screening and receipt of HPV vaccine in this population of young women,” said study leader Susan Hariri of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia.

“There is growing evidence of the population impact of HPV vaccines, and other monitoring studies have found decreases in HPV prevalence and genital warts after vaccine introduction,” but changes in screening recommendations probably also led to less detection of lesions, Hariri told Reuters Health by email.

“High-grade” cervical lesions (that is, lesions in which the cells appear very different from normal cells) don’t cause symptoms but can progress to invasive cancer if left untreated for many years. More than half of these lesions are caused by strains of HPV that can be prevented by the two HPV vaccines that became available in 2006: Gardasil and Cervarix.

All 11 or 12 year old boys and girls should get the HPV vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the new study, the researchers used data from four U.S. states collected between 2008 and 2012, intended to track the effects of HPV vaccination.

During this time, 9,119 cases of high-grade cervical cancer lesions were diagnosed among 18 to 39 year old women. Among those ages 18 to 20, lesion cases decreased dramatically over the four year period, from 94 of every 100,000 women in 2008 to five per 100,000 women in 2012 in California.

In Connecticut, the rate per 100,000 women ages 18 to 20 fell from 450 to 57.

The rate also decreased for women ages 21 to 29 in Connecticut and New York, but less dramatically, and it did not decrease for those ages 30 to 39, as reported in the journal Cancer.

Due to changing recommendations, cervical cancer screening also declined during this period, particularly among the youngest women, those ages 18 to 20. Guidelines now recommend that cervical cancer screening begin at age 21.

“The rationale for changing screening recommendations to begin screening at 21 and to screen less frequently is based on strong evidence that some HPV-associated cervical abnormalities can resolve without medical intervention, especially in young women aged less than 21 years,” Hariri said. “Also, cervical cancer is rare in young women aged less than 21 years and in general, it takes years for high-grade lesions to become severe enough to be considered cancer.”

Not screening younger women helps avoid unnecessary medical and surgical treatments in those whose precancerous lesions would likely have healed on their own, she said.

At least some of the decrease in lesions may also be due to HPV vaccination, she said.

“I don’t think you’re going to find very many medical professionals who think vaccination is a bad thing,” said Dr. Allan Covens of the University of Toronto, coauthor of an accompanying editorial in Cancer.

“The difficulty is, how do you measure success, and particularly in Canada and the U.S. where we don’t have any vaccine registries and a lot of things we’re looking for are not reportable,” Covens told Reuters Health by phone.

Australian data, which is better than North American data, indicates that the vaccine does reduce lesions, he said.

“It’s too soon to know what is causing the decline in high-grade cervical lesions and whether or not the trend will continue,” Hariri said. “We will continue to monitor and analyze subsequent years of data in order to interpret these results more accurately.”