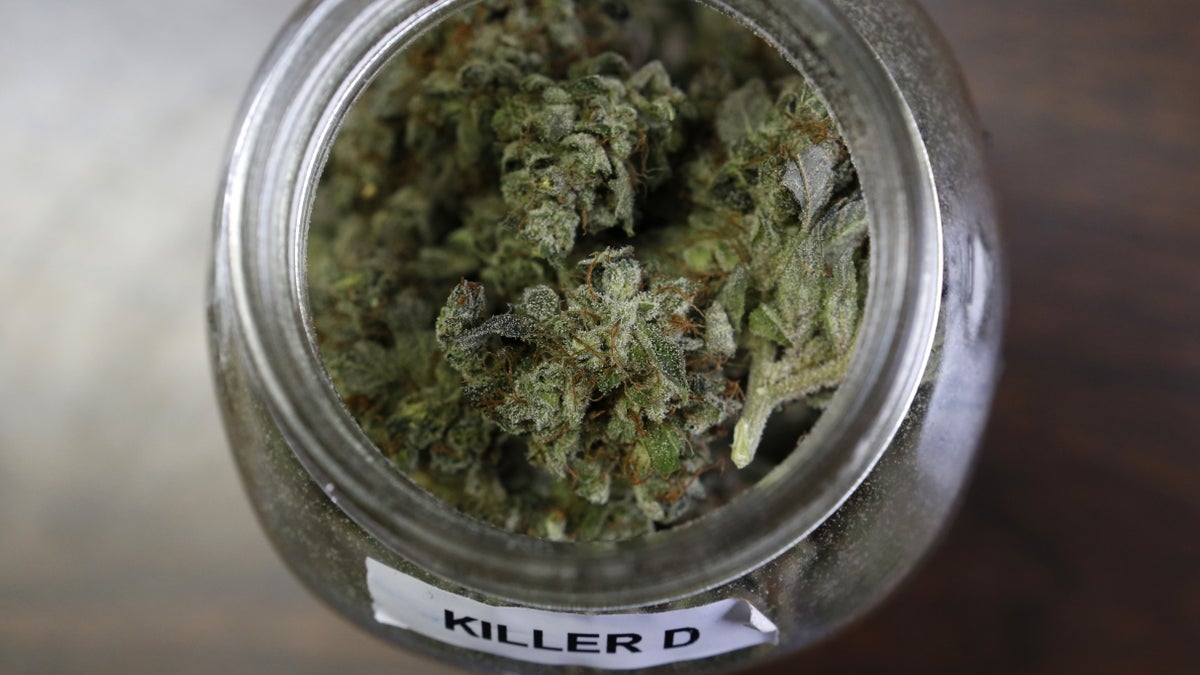

In this Friday, April 22, 2016 photo, a jar containing a strain of marijuana nicknamed "Killer D" is seen at a medical marijuana facility in Unity, Maine. A growing number of health experts and law enforcement officials are making the case that marijuana could help reduce the numbers of overdoses and redirect money into fighting heroin and other opiates. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

CONCORD, N.H. – The growing number of patients who claim marijuana helped them drop their painkiller habit has intrigued lawmakers and emboldened advocates, who are pushing for cannabis as a treatment for the abuse of opioids and illegal narcotics like heroin, as well as an alternative to painkillers.

It's a tempting sell in New England, hard hit by the painkiller and heroin crisis, with a problem: There is very little research showing marijuana works as a treatment for the addiction.

Advocates argue a growing body of scientific literature supports the idea, pointing to a study in the Journal of Pain this year that found chronic pain sufferers significantly reduced their opioid use when taking medical cannabis. And a study published last year in the Journal of the American Medical Association found cannabis can be effective in treating chronic pain and other ailments.

But the research falls short of concluding marijuana helps wean people off opioids -- Vicodin, Oxycontin and related painkillers -- and heroin, and many medical professionals say it's not enough for them to confidently prescribe it.

In Maine, which is considering adding opioid and heroin addiction to the list of conditions that qualify for medical marijuana, Michelle Ham said marijuana helped her end a yearslong addiction to painkillers she took for a bad back and neck.

Tired of feeling "like a zombie," the 37-year-old mother of two decided to quit cold turkey, which she said brought on convulsions and other withdrawal symptoms.

Then, a friend mentioned marijuana, which Maine had legalized in 1999 for chronic pain and scores of other medical conditions. She gave it a try in 2013 and said the pain is under control. And she hasn't gone back on the opioids.

"Before, I couldn't even function. I couldn't get anything done," Ham said. "Now, I actually organize volunteers, and we have a donations center to help the needy."

Bolstered by stories like Ham's, doctors are experimenting with marijuana as an addiction treatment in Massachusetts and California. Supporters in Maine are pushing for its inclusion in qualifying conditions for medical marijuana, and Vermonters are making the case for addiction treatment in their push to legalize pot.

Authorities are also desperate to curb a sharp rise in overdoses; Maine saw a 31 percent increase last year, and drug-related deaths in Vermont have jumped 44 percent since 2010. Vermont officials also blame opioid abuse for a 40 percent increase over the past two years of children in state custody.

"I don't think it's a cure for everybody," said Maine Rep. Diane Russell, a Portland Democrat and a leader in the state effort to legalize marijuana. "But why take a solution off the table when people are telling us and physicians are telling us that it's working?"

Most states with medical marijuana allow it for a list of qualifying conditions. Getting on that list is crucial and has resulted in a tug of war in many states, including several in which veterans have been unsuccessful in getting post-traumatic stress disorder approved for marijuana treatment.

"It's hard to argue against anecdotal evidence when you are in the middle of a crisis," said Patricia Hymanson, a York, Maine, neurologist who has taken a leave of absence to serve in the state House. "But if you do too many things too fast, you are sometimes left with problems on the other end."

In New Hampshire, where drug deaths more than doubled last year from 2011 levels, the Senate last week rejected efforts to decriminalize marijuana.

There are some promising findings involving rats and one 2014 JAMA study showing that states with medical marijuana laws had nearly 25 percent fewer opioid-related overdose deaths than those without, but even a co-author on that study said it would be wrong to use the findings to make the case for cannabis as a treatment option.

"We are in the midst of a serious problem. People are dying and, as a result, we ought to use things that are proven to be effective," said Dr. Richard Saitz, chair of the Department of Community Health Sciences at the Boston University School of Public Health.

Cannabis could have limited benefits as a treatment alternative, said Harvard Medical School's Dr. Kevin Hill, who last year authored the JAMA study that found benefits in using medical marijuana to treat chronic pain, neuropathic pain and spasticity related to multiple sclerosis. But he urged caution.

"If you are thinking about using cannabis as opposed to using opioids for chronic pain, then I do think the evidence does support it," he said. "However, I think one place where sometimes cannabis advocates go too far is when they talk about using cannabis to treat opioid addiction."

The findings in the Journal of Pain study that found chronic pain sufferers reduced their opioid use when using medical pot were limited because participants self-reported the data.

Substance abuse experts argue there are already approved medications. It would also be wrong to portray marijuana as completely safe, they say, because it can also be addictive.

But supporters point to doctors like Dr. Gary Witman, of Canna Care Docs, who has treated addicts with cannabis at his offices in Fall River, Stoughton and Worcester, Massachusetts.

Since introducing the treatment in September, Witman said, 15 patients have successfully weened themselves off opioids. None have relapsed.

"When I see them in a six-month follow up, they are much more focused," Witman said. "They have greater respect. They feel better about themselves. Most importantly, I'm able to get them back to gainful employment."