Coronavirus ripple effect: Medical personnel lose work amid outbreak

Hospitals, surgery centers, doctors' offices and surgeons are all out of work even as other hospitals are being overrun by coronavirus patients; William La Jeunesse reports from Los Angeles.

Get all the latest news on coronavirus and more delivered daily to your inbox. Sign up here.

Empty hospitals, closed medical clinics and unemployed surgeons: While Americans see images of an overrun health-care system, the reality nationwide is very different. Beds may be full in New York City and elsewhere, but the coronavirus has been suffocating much of the rest of U.S. medicine.

"Our physicians are seeing a reduction of 60-75 percent of inpatient visits," said Shawn Martin, a senior vice president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. "Our fear is that many physician practices will be out of business or no longer in operation because of the economic-related impact of the coronavirus."

The academy said the current shutdown could prompt roughly half of U.S. family physicians – about 58,000 in all – to close their practices and lay off hundreds of thousands of staffers.

That number would not include specialists – orthopedists, anesthesiologists, radiologists, cardiologists, etc. – many of whom cannot book operating rooms because public officials closed outpatient clinics and ordered hospitals to stop non-essential surgeries to set aside beds for COVID-19 patients.

"We've had our office close for over three weeks now where we're not providing any physical patient care procedures," Los Angeles sports-medicine specialist Dr. Steven Sampson said. "Without patients, there's no revenue to pay regular office rent and payroll and staff. So, we have temporarily furloughed our employees with the intent to bring them back when we reopen."

Primary-care practices have been down 40-50 percent, according to an association managing medical groups. Many emergency-room physicians are seeing their shifts cut.

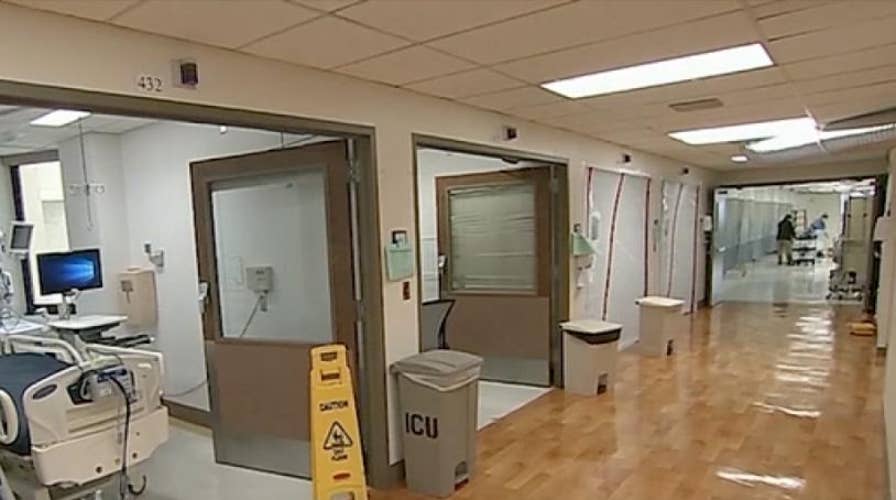

Nurses at Kaiser Permanente Hospital in Woodland Hills, Calif., said the 260-bed hospital has been nearly empty with zero COVID-19 patients and only nine of 22 ICU beds in use. In Missouri, hospitals have reported losing $32 million daily. Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson said Sunday that hospitals there have been caring for 80 coronavirus patients but some 8,000 beds have gone empty. This past Friday, Los Angeles County had nearly 1,800 unoccupied hospital beds and over 1,000 available ventilators.

CORONAVIRUS: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

"We were basically forced to close down our offices because patients were afraid to come in," said Dr. Manali Shendrikar with Santa Monica Family Physicians. "We're also seeing... a lot of asymptomatic carriers. We weren't expecting that and didn't want to keep exposing our staff."

Shendrikar has belonged to a group of 25 physicians, each of whom typically would see 18-25 patients a day. When that number fell to eight, the practice closed. Some still were seeing patients via computer or, if necessary, at a clinic nearby. One floor was reserved for COVID-19 patients, the other exclusively for those without symptoms. When patients left, they were given a nurse line and app to stay in touch with medical professionals. Still, Shendrikar said, some patients likely were not getting the care they needed.

"Some people that really need to be seen are not being seen as much as they should be," she said, "patients that have heart conditions, lung issues, chronic conditions that are not being seen routinely. We do worry about those patients. We do have a certain amount of need that is not being met because we're closed."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Sampson, like many other doctors, said telemedicine has been a savior, allowing him to stay close to patients. The federal government, for now, has let doctors bill Medicare the same amount as they would for in-patient visits, but not all insurance companies followed suit. Some have allowed only $15 reimbursements. And, while Sampson and his partners have been confident that closing the office was in everyone's best interest, he too said there was a downside that was not getting enough attention.

"We call it elective surgery, but it doesn't mean it's needless," Sampson said. "Whether it be back pain, ACL, torn meniscus, any of these kinds of things – are we potentially putting these things off and the patient is degrading and self-medicating? That's what we're going to pay for... down the line."