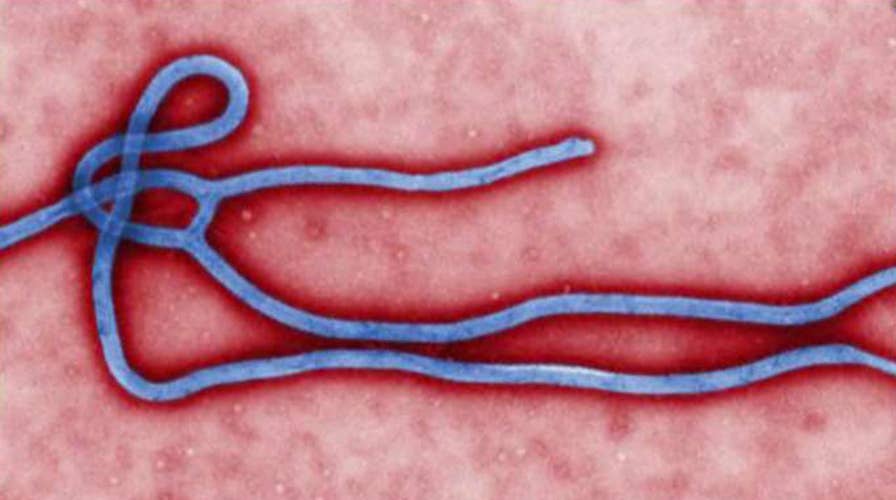

How ready are we if Ebola reaches the US?

Ebola deaths in the Congo exceed 1,000; Fox News medical correspondent Dr. Marc Siegel weighs in.

On the evening of February 24, unknown assailants descended on the Ebola Treatment Center run by Doctors Without Borders/Medecins San Frontieres (MSF) in the northeastern city of Butembo in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), partially burning the crucial health care facility to the ground.

The brazen attack came just three days after another MSF facility was bombarded and scorched in the nearby district of Katwa, and both facilities were immediately shut down for the safety of staff and patients.

Since then, attacks by armed militiamen and locals – who maintain that the harrowing contagion is a scheme brought in from the outside – on Ebola clinics have only escalated as the spread of the disease intensifies. Dozens of individual medical professionals too have been targeted by community criminals, including leading epidemiologist Richard Mouzako who was shot dead earlier this month as the attackers screamed that “Ebola doesn’t exist.”

“Insecurity is a major impediment to ensuring timely interventions with affected communities. Fundamentally, insecurity leads to lack of access, and that is what drives the increase in cases. When we cannot reach people, they do not get the chance to be vaccinated, or to receive lifesaving treatments if they fall ill,” Tarik Jasarevic, spokesperson for the UN’s World Health Organization (WHO) told Fox News. “We are anticipating a scenario that’s a lot worse than it is now. Violent incidents have a profound impact – creating fear and anxiety in the community, increasing mistrust, making it difficult for us to reach some areas because of security concerns.”

MEDICAL MIRACLES: CHILD BURN VICTIMS IN SYRIA BROUGHT TO US FOR LAST SHOT AT LIFE

The hemorrhagic fever has now been classified as the second worst Ebola epidemic; having claimed more than 1,000 lives in the African country since August, second to the 2014 eruption that killed more than 11,000 people across the continent and even infiltrated to victims in the United States.

Sept 9, 2018: A health worker sprays disinfectant on his colleague after working at an Ebola treatment center in Beni, eastern Congo. (AP)

According to WHO data, since January 2019 there have been 130 attacks that have caused 4 deaths and 38 injuries, in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Of those, 97 attacks impacted health personnel and 44 incidents impacted health facilities.

Antagonists are also reported to have ravaged handwashing appliances placed in the city over the past week; and are reported even to have unleashed on a security attachment team tending to the remains of a woman who died from Ebola.

Late last month, Reuters also reported that health care workers in Butembo took to the streets with signs reading “Ebola Exists” in protest of the burgeoning counterplots against them, and have threatened to go on strike if security is not improved – which would no doubt prove another blow to curbing the latest surge.

More than one hundred anti-government rebel groups are known to operate in the region, which has long been rocked by instability and conflict.

“Identifying specific groups responsible for specific attacks is difficult. Many of these groups resist control by the central government and they see this public health response as a threat posed by the government,” explained Gregory D. Koblentz, Director of the Biodefense Graduate Program at George Mason University. “Others have a more general suspicion of outsiders. Finally, health centers and health care workers may be caught in the cross-fire of competition between different groups. The conflict between so many armed groups is a toxic stew that makes public health campaigns exceedingly difficult.”

In addition to combatting the deadly disease’s dissemination and dire security scenario, professionals are also battling deep-seated community distrust. Rather than seeking medical help for symptoms, many locals are opting to stay home amid a spread of conspiracy theories that range from Ebola being “brought in” to the community by adversaries. It is commonly called the “Ebola business” with concerns it is merely a western for-profit scam.

More than 111,000 people have been vaccinated since the renewed flare-up nine months ago, WHO denotes, but insecurity and frets over centers coming under attack have also meant that many others in need have not obtained the vaccine. Furthermore, hearsays are running rampant that rather than being vaccinated, one will be injected as a way to expand the “Ebola business.”

INSIDE THE SECRET LIVES OF TRANSGENDER REFUGEE SEX WORKERS IN PAKISTAN

Such theories have also become political hot-buttons, with leaders of parties vowing that the outbreak last summer in the months leading up to the December elections was a mere tactic to force those in the areas not to vote.

An average of 20 new cases are being diagnosed each day, and scores of NGOs in the region concur that the situation is nothing short of “alarming.”

“The numerous new reported cases have been significantly increased over the past few weeks, reaching its highest levels since the declaration of the epidemic,” MSF said in a statement.

And Dr. Dena Grayson, a Florida-based doctor who has long-studied Ebola treatments, stressed that there is a steep concern with regards to how quickly the disease – which is transmitted through bodily fluids – could be yet another international calamity.

Aug. 8, 2018: A health care worker from the World Health Organization prepares to give an Ebola vaccination in Mangina, Democratic Republic of Congo. (AP)

“You have very densely-populated countries like Rwanda right over the border, and once in that urban setting, it is extremely difficult to contain,” she noted.

But as it stands, medical professionals are hopeful that by undertaking a “ring strategy” – which entails both vaccinating any individual directly exposed to an identified Ebola victim and a second ring of those who had that direct exposure – that the outbreak can at least be managed far better than it was almost five years ago.

“There is a major emphasis on identifying sick individuals, isolating them from the community so they can't spread the disease, contact tracing to find others who might have been infected, and safe burial of Ebola victims,” Koblentz added. “But all of this epidemiology and immunization is very labor intensive. Unfortunately, many of the NGOs have had to pull back most of their personnel due to armed conflict and attacks on health care workers and facilities. Insecurity in DRC has made it impossible for the government and international partners to contain this outbreak. The combination of an Ebola outbreak and a civil war is unprecedented and a situation the global health community is not prepared to deal with adequately.”