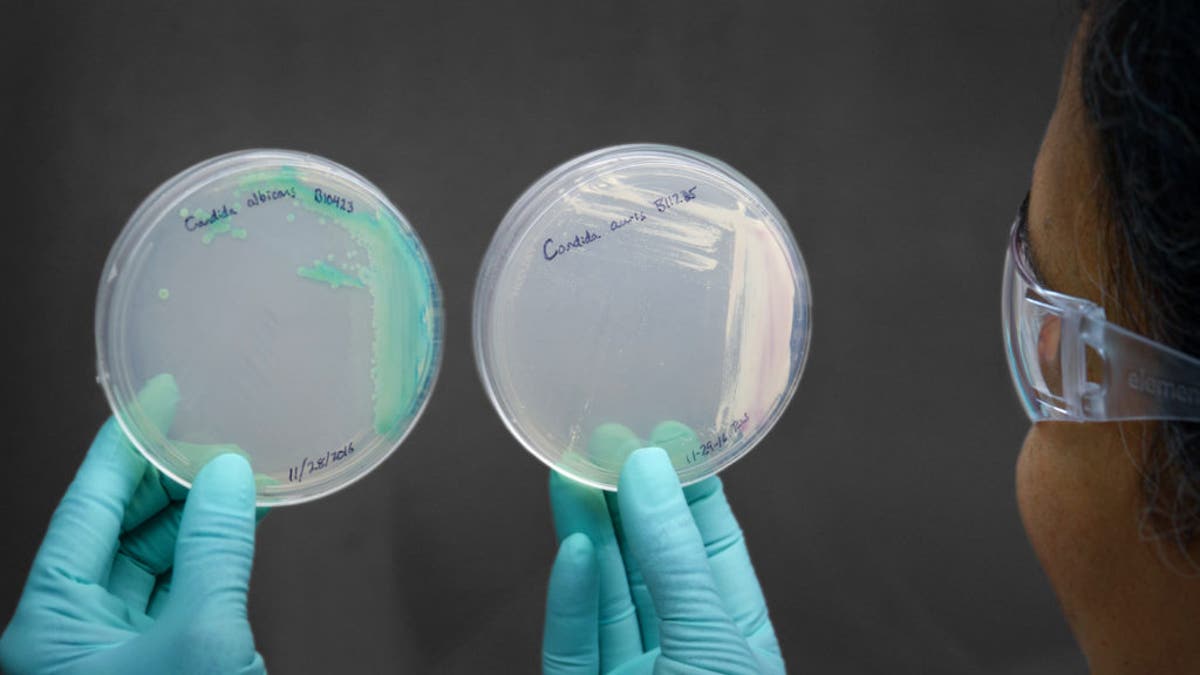

Candida plate demonstrating Candida albicans, on left, and Candida auris, on right. ((Jim Gathany/CDC))

Try as they might, the infection control specialists at Royal Brompton Hospital could not eradicate the invasive fungus that was attacking already gravely ill patients in the intensive care unit.

Enhanced cleaning didn’t stop the dangerous bug from spreading from one patient to the next in the 296-bed hospital. Neither did segregating infected patients, to keep them from spreading the fungus.

Eventually, officials who run the Royal Brompton, located a couple of miles from Buckingham Palace in London’s tony Chelsea neighborhood, resorted to a last-ditch move no hospital ever wants to have to take. They temporarily shut their ICU. That appears to have put a stop to the more than year-long outbreak, which ended last year and which involved at least 50 patients.

The lengths to which the Royal Brompton was forced to resort to rid the hospital of Candida auris — a member of a broader fungal family named Candida — raised red flags for the small community of scientists who study fungi that infect people.

“They did the Cadillac of drastic actions to make that happen, which we generally wouldn’t be doing for Candidal infections,” Dr. Tom Chiller, the chief of mycotic — fungal — diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told STAT in a recent interview.

BACK TO SCHOOL: HOW TO AVOID SCABIES INFECTION IN CHILDREN

The fear is that that’s what U.S. hospitals may be facing if C. auris breaches their infection control defenses. Last year at this time, the CDC knew of a single U.S. case, which occurred in 2013. As of mid-July, the case count had risen to 98 in nine states, though the lion’s share have been reported by two — New York (68) and neighboring New Jersey (20).

On the ever-growing list of bad bugs, C. auris is one of the most unsettling. Dr. Anne Schuchat, who served as the CDC’s acting director this spring, termed it a “catastrophic threat.”

Said Chiller: “It’s a high priority for really sick people right now and we at CDC are taking a very aggressive approach to see if we can’t control, contain, and even eradicate it from the places it exists.”

But doing that won’t be easy.

Most fungal infections are acquired when a person picks up the fungus from the environment. But it seems C. auris can be transmitted from person to person, at least in a hospital setting. The fungus is hellishly difficult to eradicate from a space, once it settles in. And some versions of it seem to be impervious to the drugs — the dismayingly few drugs, it must be noted — that combat fungal infections.

“It’s almost a perfect storm kind of organism. It has all the bad characteristics of a large number of bad pathogens,” said Dr. Alex Kallen, a medical officer with the division of health care quality promotion at the CDC.

The resistant strains of the fungus seem to be as robust as the non-resistant strains — which is a disappointment and a concern. Often organisms that develop resistance pay a price; they are weakened in the process and don’t spread as well. But with this fungus there is no “fitness” tradeoff for acquiring resistance. “And that’s again another scary thing about it. Because we don’t want fit resistant organisms,” Chiller said.

None of these dire characteristics was apparent when the fungus was first detected, in 2009. Then it was simply a new fungus grown from discharge swabbed out of the ear of a 70-year-old woman in a Japanese hospital.

Finding new additions to the fungal family tree is not uncommon; nor is it considered alarming, generally speaking.

But then the radar pinged again. Some scientists in Pakistan were investigating puzzling bloodstream infections in hospitalized patients that they thought were caused by another type of yeast, called Saccharomyces. They shipped samples to Atlanta in the hopes the CDC could help. The culprit was actually C. auris.

“That caught our attention,” Chiller admitted. “For the first time we’re like, ‘Huh? Candida auris? A cluster that big in a hospital?’”

Other countries started reporting cases. In fairly short order after the Japanese report, countries on three continents disclosed having seen infections caused by this fungus.

The widespread and virtually simultaneous appearances of C. auris raised suspicions that travelers were moving the fungus around — but that turned out not to be accurate. Comparing genetic sequences from various places showed different strains in each place — a phenomenon that remains a bit of a mystery. “It doesn’t seem like it’s one thing,” said Kallen, when asked how to explain the dissemination of the fungus.

To be clear, C. auris isn’t the zombie apocalypse. Healthy people aren’t going to be felled in the street by this fungus.

In fact, like lots of other pathogens, some of us carry Candida fungi on our skin — C. auris seems to especially like the warmth of armpits and the groin. As is true with other bugs, this fungus doesn’t generally cause problems when it’s on the outside of a healthy person being kept in check by other bugs with which it shares human turf.

It’s when someone gets sick that C. auris can become a problem. The fungus can infiltrate the bloodstream — wending its way into the body along a catheter or an intravenous line used to deliver fluids and medicines. When that happens, sick people become a lot sicker.

WHAT IS 'LEAKY GUT' -- AND HOW DO YOU KNOW IF YOU HAVE IT?

It is estimated that about five or six out of every 10 people that have been seen to be infected with C. auris die. Chiller cautioned, though, one cannot say the fungus kills 50 percent or 60 percent of its victims. As often is the case with secondary infections — bugs that infect people who are already fighting off another serious ailment — it can be tough to determine who died “from” the fungus, and in whom the infection merely contributed to the death.

Keeping C. auris from getting into and spreading within hospitals is the big goal here. But it’s likely to prove challenging. At the Royal Brompton, in London, doctors found that when a patient with C. auris was moved out of a hospital room, the next patient to move in would pick up the fungus. Even after cleaning, the fungus could be found on multiple surfaces — the bed, the floor — in the room.

The team of researchers there who investigated the outbreak declined requests for interviews.

Dr. Curtis Donskey, chief of infectious diseases at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, has been studying C. auris in the laboratory, trying to determine how long it can survive on surfaces in hospitals and which cleaning regimens can effectively destroy it.

In an upcoming paper, he and colleagues will report that the disinfectants most commonly used in U.S. hospitals are not that effective against this fungus.

They also found that C. auris is able to live on surfaces for at least seven days. And that is probably not the end of the C. auris story. “We certainly suspect that they would last longer than that,” Donskey said. “That’s just how long we tested.”

Aware of this problem, the CDC has recommended hospitals use bleach to clean rooms that housed patients with C. auris. But that’s not a fail-safe solution. “We found more of it on moist surfaces that are not typically cleaned with bleach at all,” said Donskey, pointing to sink drains.

And bleach isn’t the easiest of cleaning regimens. “It’s damaging, it doesn’t smell good, causes occupational health issues,” CDC’s Kallen said.

Likewise, there are surfaces hospitals might not think to clean between every patient that can harbor the bacteria — for instance, the privacy curtains that separate patients in a multi-bed room.

Adopting the enhanced cleaning techniques used to control C. difficile — a bacteria that forms a spore and is also challenging to control — should help with C. auris, said Donskey.

He’s hoping, though, that the lessons hospitals learned as they battled that bacteria — for example, clean those privacy curtains after a patient with C. difficile is moved out of a room — will give them a head start in the era of C. auris.

“I think that the environment is much more appreciated now than it was a decade ago as a source for transmission,” he said. “And I think we would do the same things if we see Candida auris that we already are very well used to for trying to control C. diff and other pathogens.”