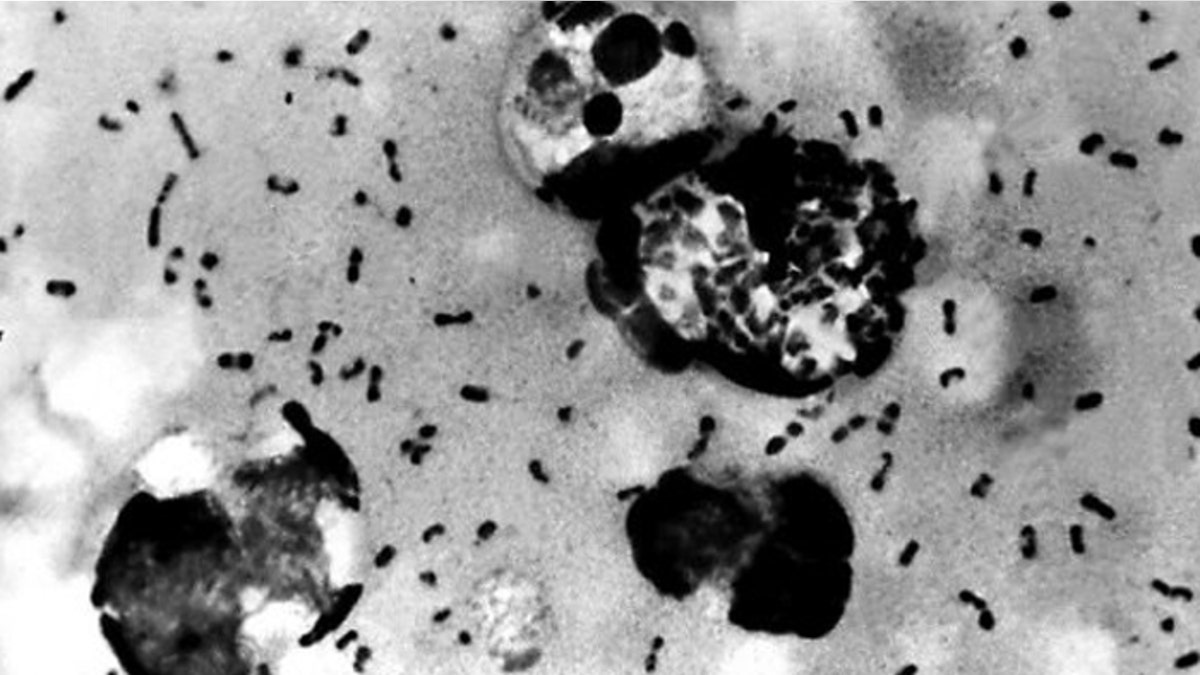

Bubonic plague bacteria from a patient, in a photo obtained on 15 January 2003 from the US Centers For Disease Control. (CDC/AFP/File)

Measles, tuberculosis… bubonic plague?! If headlines about old-time diseases on the comeback have you worried, you’re not alone. Here’s what you need to know to stay safe (and sane) amid recent outbreaks.

Plague

Think this notorious killer died with the Middle Ages? The disease actually persists in parts of Africa, Asia, and South America. And there have been 16 reported cases of plague, with four deaths, in the United States this past year. Most recently, a 16-year-old girl from Oregon was sickened and hospitalized after apparently being bitten by a flea on a hunting trip.

You can get plague from fleas that have carried the Yersinia pestis bacteria from an infected rodent, or by handling an infected animal, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Bubonic plague is the most common form in the U.S., while pneumonic plague (affecting the lungs) and septicemic plague (affecting the blood) are less prevalent but more serious. Symptoms of bubonic plague include fever, chills, headache, and swollen lymph glands.

RELATED: 15 Diseases Doctors Often Miss

The good news is that plague is extremely rare, has a very low risk of person-to-person transmission, and can be effectively treated with antibiotics, explained Dr. Michael Phillips, associate director of the division of infectious diseases in the department of medicine at NYU Langone Medical Center. (The bad news is that plague can be fatal if treatment isn’t started within 24 hours of the arrival of symptoms.)

To stay safe, avoid contact with wild rodents (that means squirrels and chipmunks, in addition to rats), steer clear of dead critters, and call your doctor if you develop any symptoms after being exposed to fleas or rodents, particularly in western states, where U.S. cases tend to occur.

“While we can expect to see occasional cases in parts of America, it’s highly unlikely that there would be a wide-scale outbreak,” Phillips said. “As long as you’re not mucking around where you might come up against mice and fleas, you don’t have to worry.”

Mumps

Once a common illness among children and young adults, cases of mumps in the US have dropped by 99 percent since a vaccine was introduced in 1967. But occurrences crop up, particularly among close-knit communities. The CDC reports that there have been 688 reported cases of mumps in the US in 2015, including small outbreaks at universities in Pennsylvania, Iowa, and Wisconsin. In 2014, there was a mini-outbreak among professional hockey players.

The virus that causes mumps is spread in close quarters (think college dorms or locker rooms) via coughing, sneezing, talking, or sharing cups or eating utensils. Symptoms of mumps include fatigue, fever, head and muscle aches, and loss of appetite, followed by puffy cheeks caused by swelling of the salivary glands. There is no treatment, but most people recover fully in a few weeks. Complications are rare, but can include hearing loss, meningitis, and inflammation of the testicles or ovaries.

RELATED: 12 Facts You Should Know About Ovarian Cysts

The only way to prevent the mumps (aside from avoiding people with it) is to get the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine. Though usually administered to kids, you can get the vaccine at any time. It’s not foolproof (two doses are 88 percent effective at preventing the disease, per the CDC), and its protection can wear off over time, but it’s vastly better to get the shot than not. Booster doses are often recommended during outbreaks.

Measles

Like mumps, measles was once widespread: in its heyday, nearly every American child got the disease before they turned 15, and an estimated 400 to 500 Americans died from it each year, according to the CDC. Widespread adoption of the vaccine in the 1960s, however, led to the elimination of the disease from the U.S. in 2000.

Not so fast: measles has made a troubling comeback of late, with a spike of 667 cases reported in 2014, and another 189 in 2015. Many of this year’s cases stemmed from an outbreak at two Disney theme parks in California.

The virus that causes measles is spread via coughing and sneezing, and is so contagious that 90 percent of non-immune people near someone infected will get it, according to the CDC.

“It travels like a gas through the air,” Phillips said, making it “the ultimate transmissible infection.”

Symptoms of measles include fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes, and a rash that typically begins at the hairline and spreads downward across the body. Complications can include diarrhea and ear infections, and in rare cases, life-threatening pneumonia and encephalitis.

There is no treatment, which makes vaccination imperative. Experts have attributed the recent surge to lax vaccination habits; in some cases, unvaccinated people may have picked up the bug overseas and spread it to communities of unvaccinated people. Two doses of the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine are about 97 percent effective at preventing the disease; it’s particularly important to get vaccinated if you’re traveling internationally.

“Prevention is the hallmark,” Phillips said. “If we develop pockets of under-vaccinated people and start having enough transmission, even those individuals who are vaccinated will be at risk.”

RELATED: Adult Vaccines: What You Need and When

Tuberculosis

Leading up to the 1882 discovery of the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis, this scourge killed one out of every seven people living in the United States and Europe. Antibiotics have dramatically reduced its deadliness, particularly in the US, and as recently as the 1990s it was believed that tuberculosis could be eliminated from the world by 2025, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. But it persists, killing between 2 and 3 million people globally each year. Though most Americans don’t consider TB a threat, it’s showing signs of a resurgence: there were 9,421 reported US cases of TB in 2014, according to the CDC, and 555 deaths in 2013 (the last year for which data are available). Recent cases include three teachers at a New York City elementary school, a San Antonio high school student, and another high school student outside of San Diego.

TB is caused when Mycobacterium tuberculosis attacks the lungs. It’s spread through the air when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks (though not by shaking hands, kissing, or sharing food, drink, or toothbrushes). People with compromised immune systems are especially vulnerable. Symptoms of TB include a cough that lasts three weeks or longer, often producing blood, as well as fatigue, fever and weight loss.

“Many cases we’re seeing involve folks who were infected years before, were asymptomatic, and then the disease reactivates later in life,” explained Phillips.

The good news is that TB is curable with treatment, though several different antibiotics must be taken over 6 to 12 months. To stay safe, avoid contact with TB patients, particularly in crowded, enclosed environments. If you think you may have been exposed to someone with TB, see your doctor immediately for testing and possible treatment.

TB is scary enough on its own, but health professionals are particularly worried about the rise of antibiotic-resistant TB throughout the world.

“We’re seeing more and more cases that are multi-drug-resistant, which means it requires a second or a third line therapy to treat,” Phillips said. “We have to think globally about this one: helping to prevent cases overseas and working on new drug development can only help keep us safe domestically.”

Scarlet fever

Largely forgotten over the past century thanks to the rise of antibiotics, this bacterial infection is perhaps best known for the role it plays in the classic children’s book The Velveteen Rabbit. (When the young protagonist comes down with scarlet fever, all his toys, including his beloved rabbit, must be destroyed, on doctor’s orders.)

Researchers have recently been tracing scarlet fever’s comeback in Asia (with more than 5,000 cases over the past five years in Hong Kong and 100,000 in China) and the United Kingdom (roughly 12,000 cases over the past year).

RELATED: The 20 Biggest Lessons We Learned About Our Health in 2015

Caused by the same type of bacteria behind strep throat (Streptococcus), scarlet fever commonly afflicts children ages 5 to 12, and shares many symptoms with strep (fever, sore throat, headache, nausea), along with a red, sandpapery rash that appears on the chest and neck and may spread across the body. Like strep, scarlet fever can be diagnosed via a throat swab or throat culture, and can be effectively treated with antibiotics. Researchers are concerned, however, that newer outbreaks may be related to antibiotic resistance, which can make scarlet fever harder to knock out with drugs.

To stay safe, avoid contact with infected people (the disease spreads via sneezes or coughs), wash your hands regularly (as you would to ward off any communicable disease), and seek treatment as soon as symptoms develop.

“It’s easily transmitted in group settings,” Phillips said, “so there is the risk that when a toxigenic strain moves into a community, it would spread rapidly.”