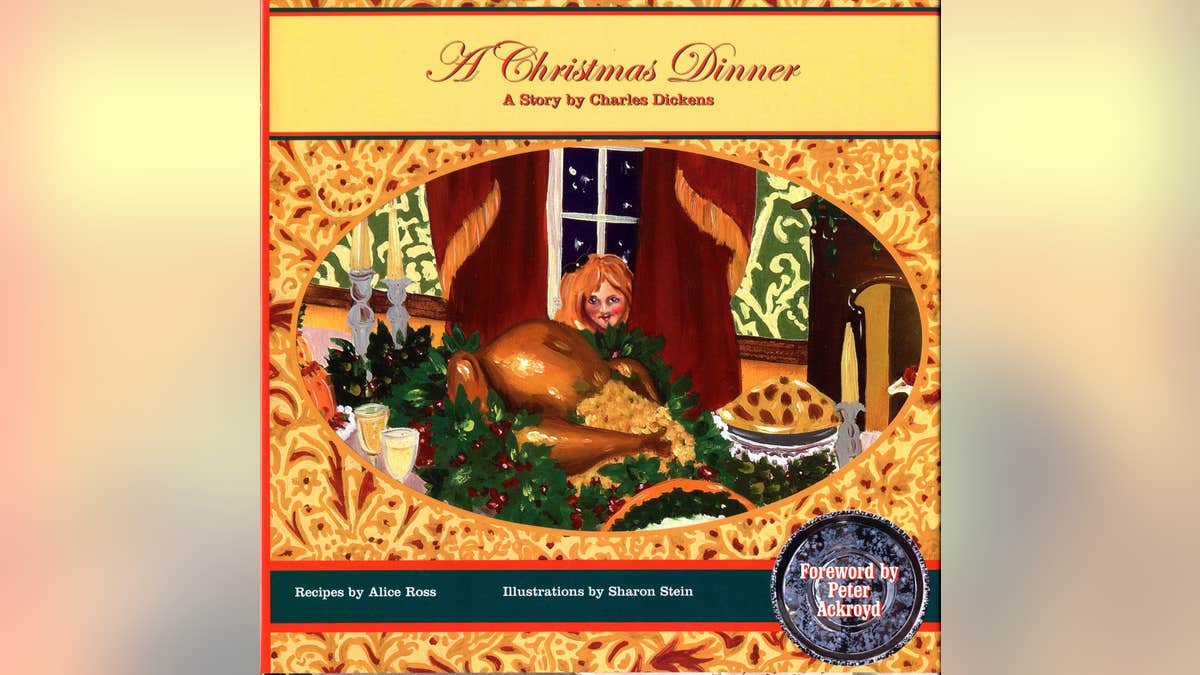

A Christmas Dinner (Red Rock Press)

Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” (1843) may be one of the most famous holiday tales extant, but it was his “A Christmas Dinner” (1835) that helped define the concept of “Christmas spirit” and set the stage for many of the traditions and foods that we enjoy to this day.

“He made it comfortable,” writes Dickens historian Peter Ackroyd in the foreword to the latest reissue of the book by Red Rock Press. “He made it cozy; he made it immune to the threatening world outside. It became the celebration of a small and close-knit community within a lighted room.” Dickens didn’t invent Christmas, but he couched it in a philosophy and centered it on an image that compelled people to see it and feel it as he did.

“There seems a magic in the very name of Christmas,” writes Dickens, when “petty jealousies and discords are forgotten” and father and son, brother and sister, “bury their past animosities in their present happiness.” In addition to placing holiday festivities squarely within the family circle, Dickens and his wife are also largely responsible for establishing the modern Christmas dinner menu.

This version of “A Christmas Dinner” also contains contemporary nineteenth century Christmas Eve and Christmas Day menus - including a few recipes from the Dickens household - assembled by distinguished culinary historian, Alice Ross. Ross researched the foods of the era and unearthed the original recipes, bringing them into the twenty-first century by updating measurements, techniques and instructions.

A nineteenth-century housewife cooked by judging the amount of ingredients in pots and the heat of fires by how they felt in her hands. Temperature settings and cooking times, as we know them, didn’t exist. If she were “planking a cod,” that meant rubbing melted butter on a cod fillet then tying it to a damp wooden board. She then leaned the plank against the fireplace wall to broil the fish, turning it upside down halfway through cooking and touching it to test for doneness. She had to be attentive to the properties of the foods she prepared. Cooks had an idea of what a dish should taste like and worked towards that idea. “Taste, touch, smell and sound were chief guideposts for judging a dish’s progress,” writes Ross.

Much like today, people in the nineteenth century didn’t always make their own food. They would eat at local inns or taverns and since fuel was expensive, families would often buy meat and take it to the local grocer who would cook it for them. There were also those to whom cooking was simply fascinating – forbears of today’s Food Network viewers. Dickens and his wife, Catherine Hogarth, whom he married in 1836, were among them. The vision set forth in “A Christmas Dinner” of a forgiving and jovial family preparing and enjoying a feast of turkey, Christmas pudding, mincemeat pies and holiday punch came together for Dickens around the time he married.

It’s not that Christmas wasn’t celebrated, or fine meals not prepared until Dickens came along. Some families went over the top, but observing the day, even in a purely religious sense, was on the wane at the time. Dickens reversed that trend and expanded the idea of the holiday. “Christmas Time!,” he writes, “that man must be a misanthrope indeed, in whose breast something like a jovial feeling is not roused - in who mind some pleasant association are not awakened - by the recurrence of Christmas.” He made celebrating it universal.

Queen Victoria did her part to expand Christmas as well. She ascended the throne in 1837 and married Prince Albert in 1840. Albert brought traditions like Christmas trees, stockings, cards, cakes and candies from his native Germany, and Victoria made sure they became England’s as well. When it came to food, however, Dickens’ insistence on traditional English foods at Christmas simply wasn’t on her radar.

Nineteenth Christmas morning breakfasts were modest unless you had a house full of family and friends. Then, says Ross, it would typically include kippered fish, eggs, fried mashed potato balls, deviled fowl, kidney cutlets, pigeon pie, ham, pudding, fruit bread, butter, jam, marmalade and tea.

The foods that were eaten and how they were prepared were central to Charles and Catherine Dickens’ ideas about Christmas, says Ross, who used Catherine Dickens’ diary as a primary source for this book. The Dickenses had a huge collection of pots and pans and shopped for food together every day. He often did half the cooking, says Ross, “he loved food.” They eventually hired a cook and kitchen staff, which gave Catherine Dickens time – after having ten children - to write a cookbook.

Ross includes recipes from Lady Maria Clutterbuck’s [Catherine Dickens’ pseudonym] “What Shall We Have For Dinner?” (1852) and sourced from other period cookbooks such as, “A Lady, The New London Cookery” (1838) and “The Female Instructor or Young Woman’s Friend and Companion” (1837), which also contained diagrammed charts for placing foods and decorative candlesticks on the table.

There’s Mrs. Dickens recipe for Cock-A-Leekie Soup, which originated in medieval times in her native Edinburgh and calls for five to six pounds of beef or veal, a five- to six-pound chicken, water, leeks and prunes. Kalecannon, a Celtic cabbage and potato dish, was a favorite of hers, though Mrs. Dickens substituted spinach for cabbage. Cod with Oyster Sauce is another dish she favored, which calls for pouring fresh oyster stew made with cream, nutmeg, butter and flour over poached cod.

Dickens loved Christmas and its foods and he wanted to make sure that the culinary traditions he remembered from his childhood and the ones he established with his wife and children were here to stay. Says Ackroyd, “Dickens’ image of Christmas of beneficence and communal happiness never left him. If was for him the paradigm of an ideal human society, a society held together by mutual respect and mutual responsibility - with plenty of turkey and mince pies thrown in.”