Fate reunited this community leader with the man who shot him

Damion Cooper thought he'd finally forgiven his unknown shooter. Then he found himself sitting across from the young man while volunteering in a Baltimore prison.

BALTIMORE – Damion Cooper had his headphones on as he left the number five bus to walk to his mother's house for dinner after wrestling practice at Coppin State University. But just steps from her home, he felt a presence behind him.

He turned and saw two men. One raised a gun. Then it felt like a sledgehammer was repeatedly hitting him just above the heart.

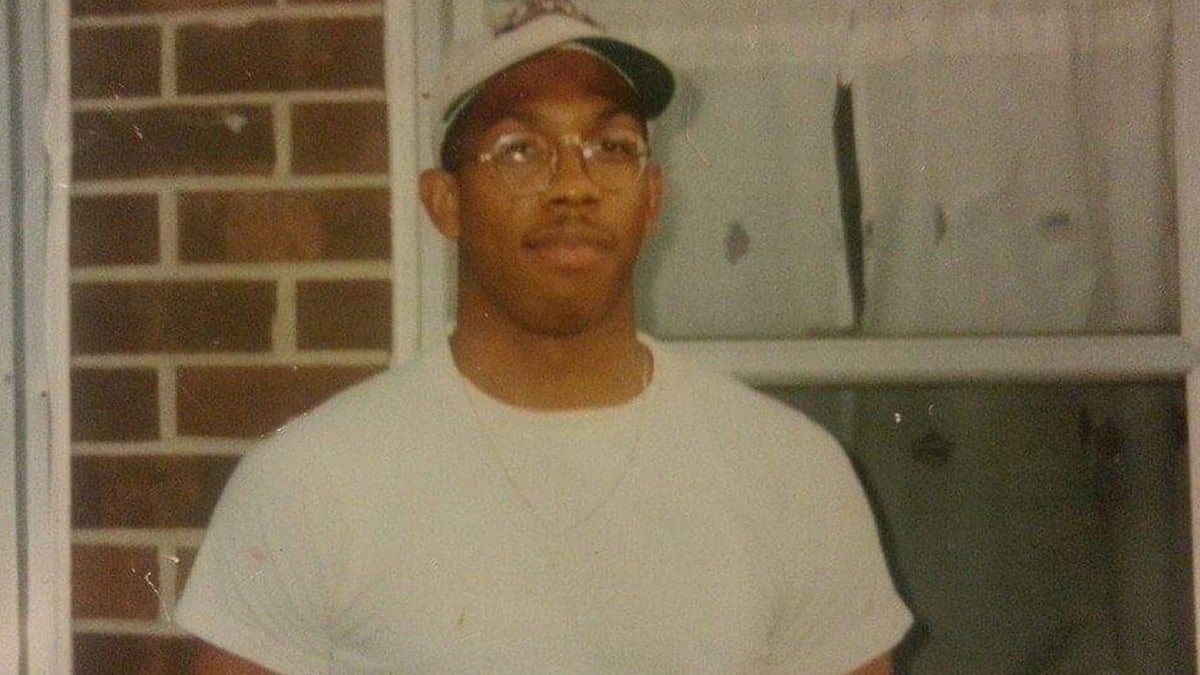

Damion Cooper pictured in 1992, the year he was shot while walking to his mother's house for dinner. (Courtesy Damion Cooper)

BALTIMORE MAYOR WANTS SUMMERTIME YOUTH CURFEW AFTER 2 TEENS SHOT OVER WEEKEND: 'NOT NORMAL'

"I just kept choking off my own blood," Cooper said, recalling how his stepfather ran out of the house, his sister screaming his name over and over.

In the ambulance, the paramedic made no bones about Cooper's prospects.

"Baby, if you close your eyes, you're not gonna open them," she said. "I want you to count every single streetlight as we drive to the hospital."

Cooper narrowly escaped becoming another Baltimore homicide victim that day. Drug wars and rampant crime left 333 people dead in 1992, a two-decade high. Last year, the same number of people were killed.

Yet Cooper made it to the hospital and through the long recovery from a cracked sternum, broken ribs and a punctured lung. But Cooper said he lost himself.

"I became very angry, very depressed, just disenfranchised to the world," he told Fox News. "I literally blamed God for me getting shot. I was like, ‘How could you let me get shot of all people when you got people selling drugs? You got people hurting people?’"

FATE REUNITED THIS COMMUNITY LEADER WITH THE MAN WHO SHOT HIM:

WATCH MORE FOX NEWS DIGITAL ORIGINALS HERE

On New Year's Eve four years later, Cooper was sitting at home alone, planning to take his own life. As he waited for midnight, the doorbell rang. His friends were there, worried about him. They begged him to go to church with them.

So he gave in and sat angrily in the pew, listening as a pastor read a psalm that would change his life: "For his anger endures but a moment; in his favor is life: weeping may endure for a night, but joy comes in the morning."

Cooper had never been an emotional person. He didn't even cry when he got shot. But at that psalm, he broke down in tears. He forgave the man who shot him, even though he didn't know his name. He finished his degree in marketing and decided to go to seminary.

He started mentoring prisoners in Baltimore, preparing young men to be released back into society. For a year and a half, he had no idea that one member of his group was the man who had shot him years earlier.

"It got to the point where his life kept coinciding with my life a little bit too much," Cooper said.

So he asked the young man one day, "Have you done anything that you're not proud of?"

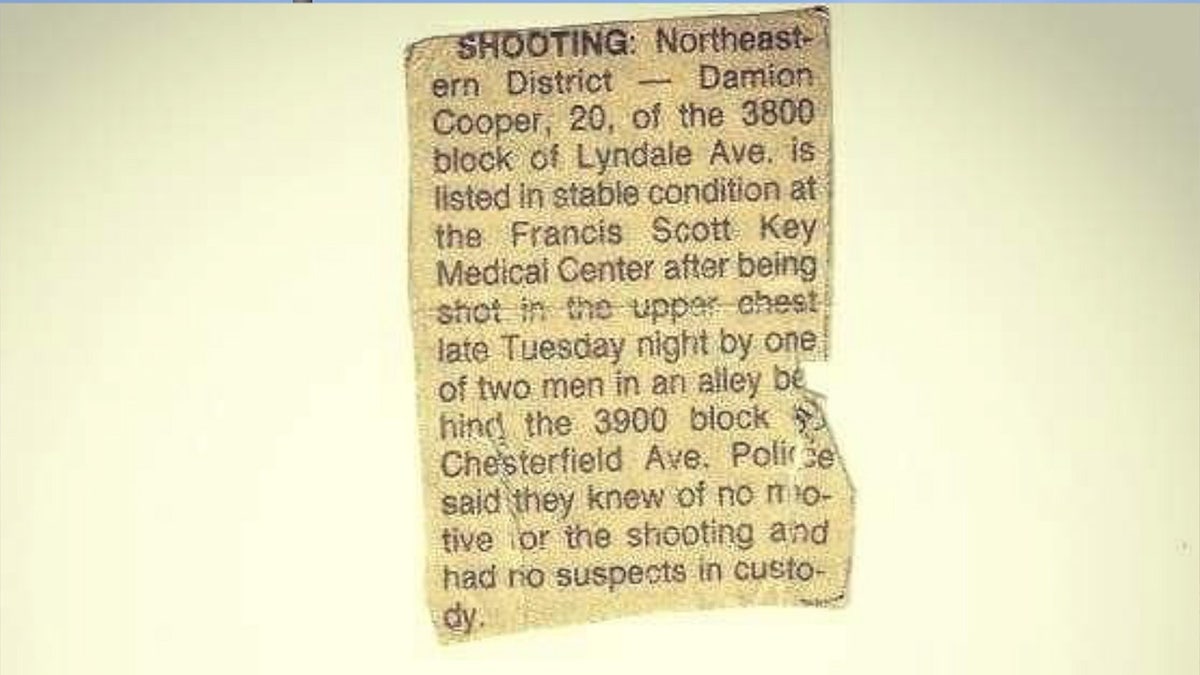

A newspaper clipping details Cooper's shooting in 1992. (Courtesy Damion Cooper)

BALTIMORE POLICE STAFFING CRISIS HITS DIRE LEVELS, FOP BOSS AND JUDGE WARN: ‘UNDERCOVER’ DEFUNDING

The young man listed a few acts. Then he started describing a time he and a friend followed a man off the number five bus.

"'We ran up on him, and this dude didn't even hear us,'" Cooper recalled the man telling him. "'When he turned around, I blasted him.'"

Cooper's blood ran cold. He loosened his tie and unbuttoned his shirt, peeling it back to reveal the scar above his heart. "You shot me," he told the other man, who turned beet red, frozen with shock.

"I forgave him that night in church," Cooper said. "I looked at him in his face and I told him, ‘I forgive you.’"

Years later when Cooper was anonymously nominated for a $10,000 grant, he used the money to start a program for boys in Baltimore acting out in school. He wanted to make sure they didn't go down the same path as his attackers.

A Baltimore police officer trainee and two boys play outside during an April 19 event at the Under Armour headquarters. (Megan Myers/Fox News Digital)

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

He called it Project Pneuma, after the Greek word for "breath."

The program uses activities like yoga and fitness competitions with Baltimore police trainees to bolster boys' mental health and prevent them from joining violent gangs.

"It's personal to me because I believe God breathed new life into me when I got shot," he said. "And it's our job to breathe new life into these young boys who don't often see another day."