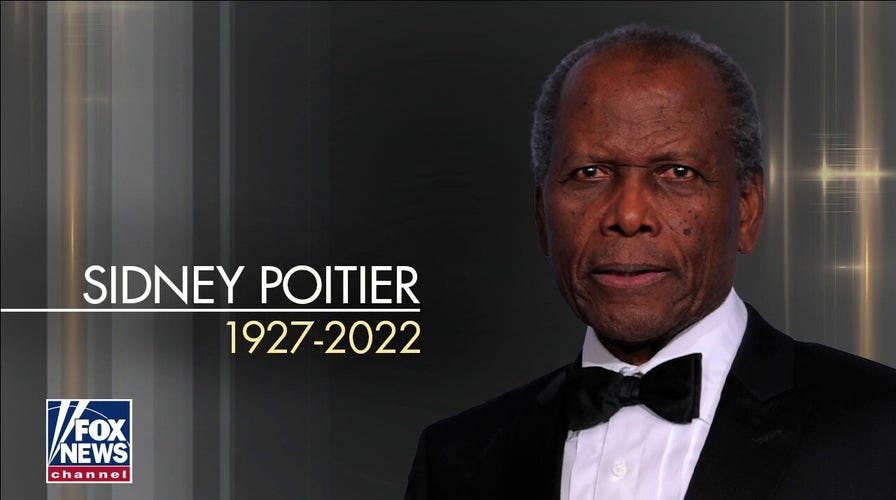

Actor Sidney Poitier dead at 94

Hollywood legend was first Black performer to win Oscar for Best Actor

Sidney Poitier, the beloved Oscar-winning actor, has died. He was 94.

The star's death was confirmed to Fox News on Friday by the Bahamian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Office. Prime Minister of the Bahamas Philip Davis also held a press conference on Friday morning where he remembered the film icon as an "actor and film director, an entrepreneur, civil and human rights activist and, latterly, a diplomat.

"We admire the man not just because of his colossal achievements but also because of who he was: his strength of character, his willingness to stand up and be counted, and the way he plotted and navigated his life’s journey," Davis said.

PETER BOGDANOVICH, OF 'PAPER MOON' FAME, DEAD AT 82

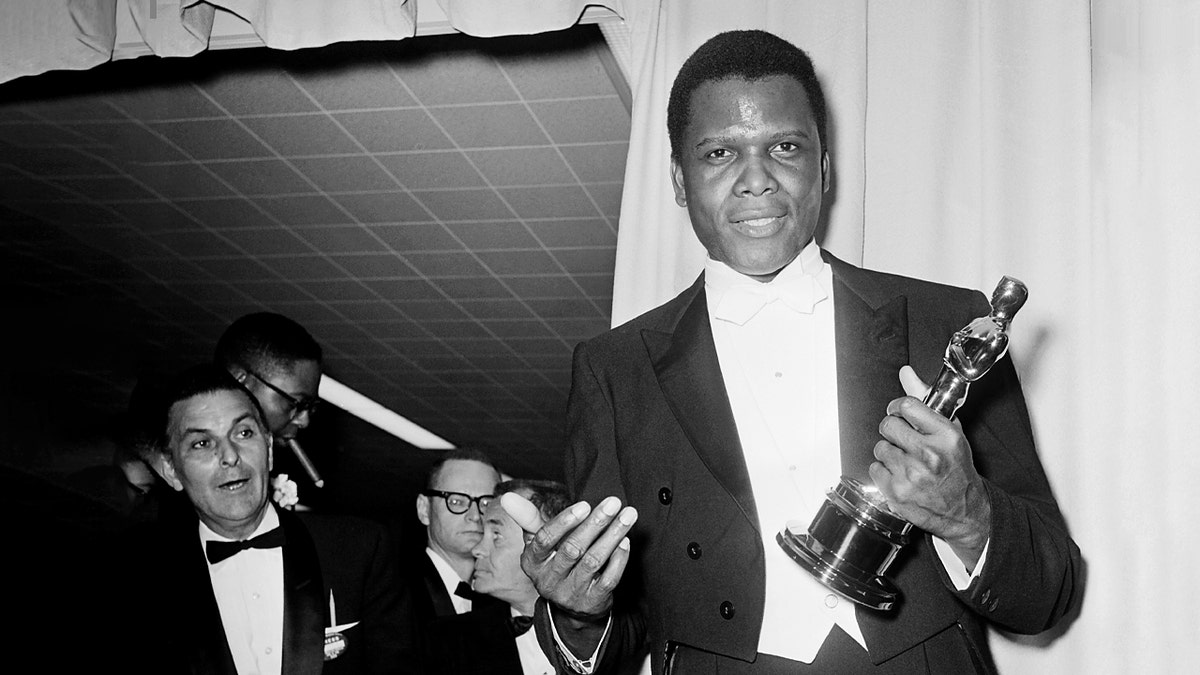

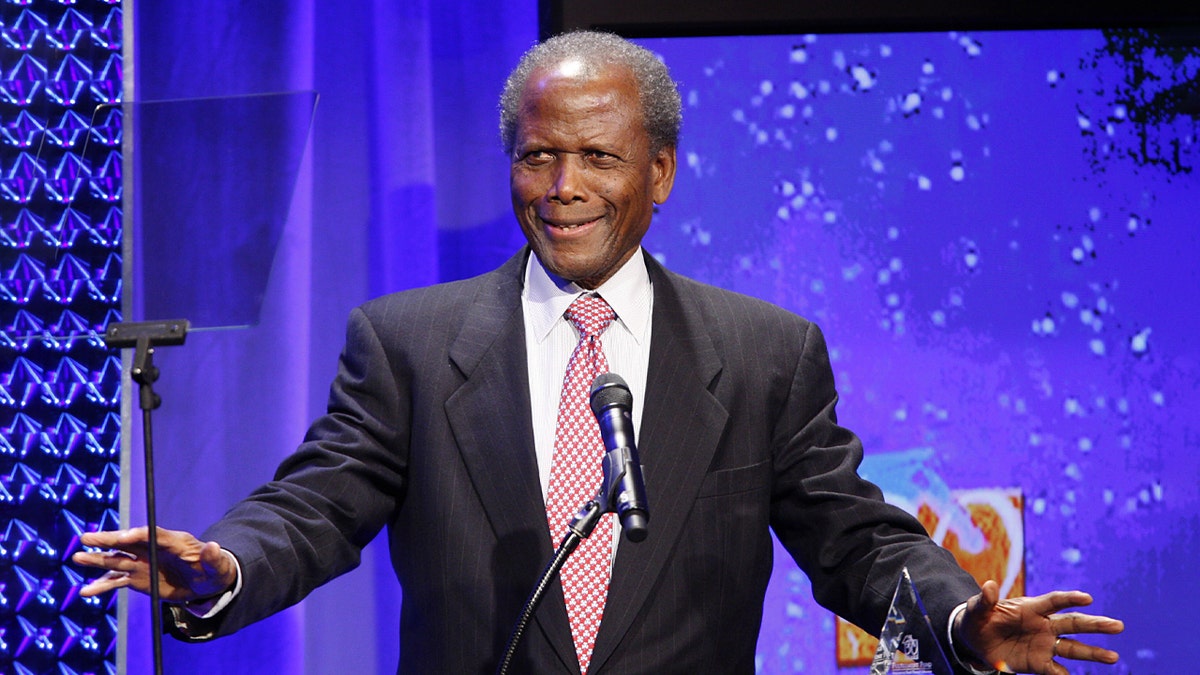

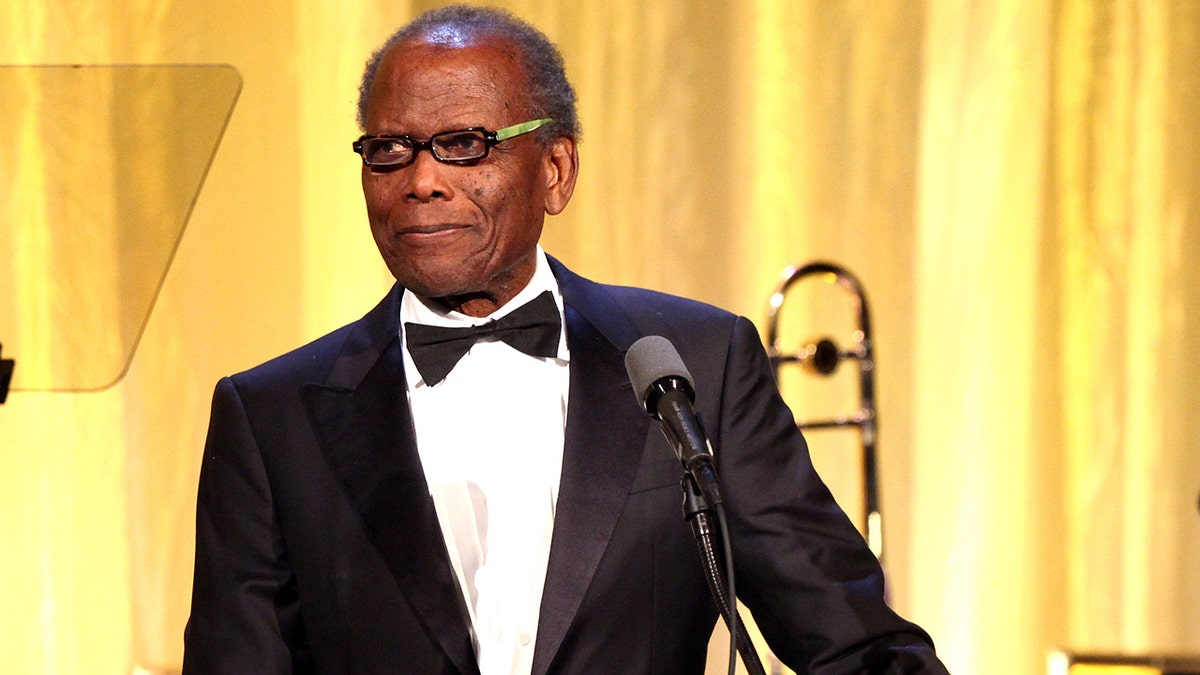

Poitier became the first Black winner of a lead-acting Oscar. (Paul Archuleta/FilmMagic)

Davis shared the country is "in mourning." He instructed the Bahamian flag be flown at half-mast "at home and in our embassies around the world.

"We know the world mourns with us. Sidney’s light will continue to shine brightly at generations to come," the prime minister added.

Davis concluded the press conference by fielding questions from the press, during which he admitted more should be done to mark Poitier's legacy in the Bahamas, where he grew up.

"We intend to sit as a government to determine what else we can do to mark his bearing in the Bahamas and the world," the prime minister said.

In 1963, Poitier made a film in Arizona, "Lilies of the Field." The performance led to a huge milestone: He became the first Black winner of a lead-acting Oscar. As one of the most beloved stars of Hollywood's golden era, Poitier made his mark with films like "A Raisin in the Sun," (1961) "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner" (1967) and "Uptown Saturday Night," (1974), among others.

In January of this year, Arizona State University has named its new film school after him. The Sidney Poitier New American Film School was unveiled at a virtual ceremony.

BETTY WHITE’S ILLINOIS HOMETOWN SEEKS TO HONOR LATE TV ICON

The decision to name the school after Poitier is about much more than his achievements and legacy, but because he "embodies in his very person that which we strive to be — the matching of excellence and drive and passion with social purpose and social outcomes, all things that his career has really stood for," said Michael M. Crow, president of the university.

Sidney Poitier and Dorothy Dandridge filming ‘Porgy and Bess', circa 1959. (George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images)

"You’re looking for an icon, a person that embodies everything you stand for," Crow said in an earlier interview. "With Sidney Poitier, it’s his creative energy, his dynamism, his drive, his ambition, the kinds of projects he worked on, the ways in which he advanced his life."

Actor Sidney Poitier and his daughter, actress Sydney Tamiia Poitier, arrive at the Vanity Fair Oscar Party in West Hollywood, Los Angeles, USA, 02 March 2014. (Hubert Boesl/picture alliance via Getty Images)

"Look at his life: It’s a story of a person who found a way," he said of the actor, who was born in Miami and raised in the Bahamas, the son of tomato farmers, before launching a career that went from small, hard-won theater parts to eventual Hollywood stardom. "How do we help other young people find their way?"

The university said it invested millions of dollars in technology to create what’s intended to be one of the largest, most accessible and most diverse film schools. Crow said that much like the broader university, the film school will measure success not by exclusivity but by inclusivity.

The school will move in the fall of 2022 to a new facility in downtown Mesa, Arizona, which is seven miles from the university’s Tempe Campus. It will also occupy the university’s new center in Los Angeles.

Scene from Columbia's Stanley Kramer production 'Guess Who's Coming to Dinner?' circa 1967. Written by William Rose, directed by Stanley Kramer. Scene shows Sidney Poitier and Katharine Houghton (niece of actress Katharine Hepburn). (Photo by George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images)

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

While Poitier had been out of the public eye for some time, his daughter Beverly Poitier-Henderson told The Associated Press her father was "doing well and enjoying his family," and considered it an honor to be the namesake of the new film school.

Poitier was born in 1927 in Miami, Florida, PBS shared. The star grew up in the small village of Cat Island, Bahamas. His father, a tomato farmer, moved his family to the capital when Poitier was 11. At a young age, Poitier was captivated by cinema and, at age 16, he moved to New York. He found work as a dishwasher and soon after, became a janitor for the American Negro Theater in exchange for acting lessons.

It was there where Poitier was given the role of understudying Harry Belafonte in "Days of our Youth." Poitier made his public debut while filling in one night. Afterward, he earned a small role in the Greek comedy "Lysistrata." Poitier continued to perform in plays until 1950 when he made his film debut in "No Way Out."

Poitier is celebrated as a groundbreaking actor and enduring inspiration who transformed how Black people were portrayed on the big screen. Before Poitier, no Black actor had a sustained career as a lead performer or could get a film produced based on his own star power.

Before Poitier, few Black actors were permitted a break from the stereotypes of bug-eyed servants and grinning entertainers. Before Poitier, Hollywood filmmakers rarely even attempted to tell a Black person’s story.

Poitier’s rise mirrored profound changes in the country in the 1950s and 1960s. As racial attitudes evolved during the civil rights era and segregation laws were challenged and fell, Poitier was the performer to whom a cautious industry turned for stories of progress.

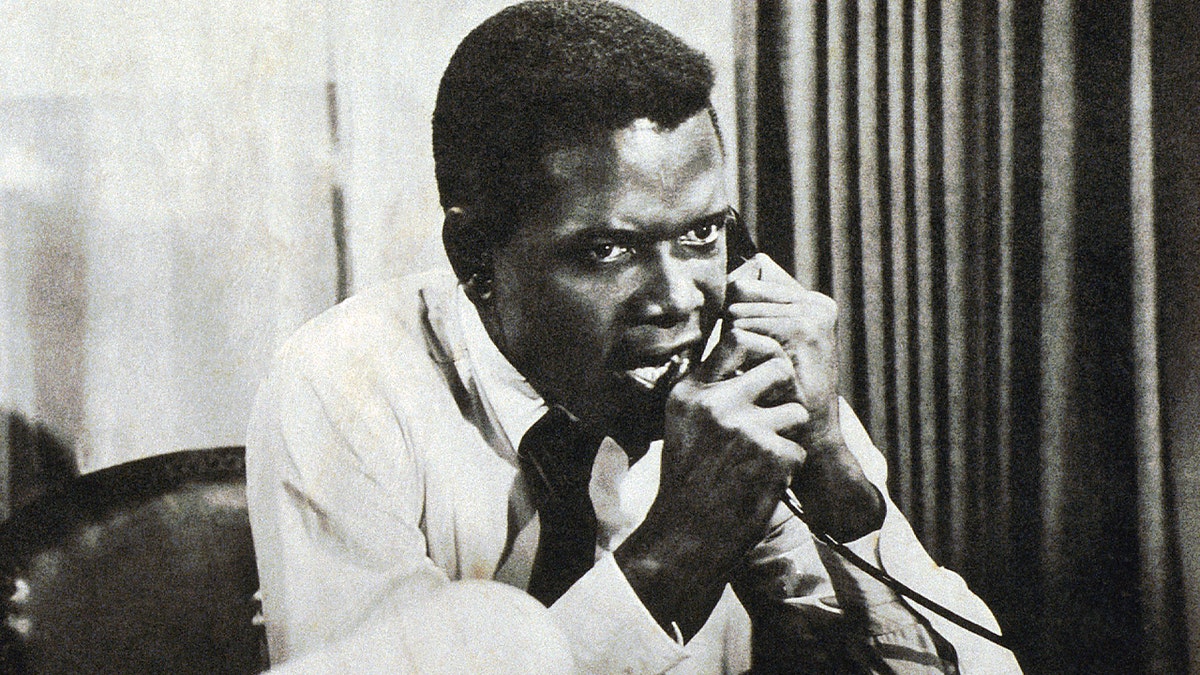

In New York City, Sidney Poitier was looking in the Amsterdam News for a dishwasher job when he noticed an ad seeking actors at the American Negro Theater. He went there and was handed a script and told to go on the stage. Poitier had never seen a play in his life and could barely read. He stumbled through his lines in a thick Caribbean accent and the director marched him to the door. Still, that didn't stop him from pursuing his passion to perform. (Photo by LMPC via Getty Images)

He was the escaped Black convict who befriends a racist white prisoner (Tony Curtis) in "The Defiant Ones." He was the courtly office worker who falls in love with a blind white girl in "A Patch of Blue." He was the handyman in "Lilies of the Field" who builds a church for a group of nuns. In one of the great roles of the stage and screen, he was the ambitious young father whose dreams clashed with those of other family members in Lorraine Hansberry’s "A Raisin in the Sun."

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR THE ENTERTAINMENT NEWSLETTER

Debates about diversity in Hollywood inevitably turn to the story of Poitier. With his handsome, flawless face; intense stare and disciplined style, he was for years not just the most popular Black movie star, but the only one.

"I made films when the only other Black on the lot was the shoeshine boy," he recalled in a 1988 Newsweek interview. "I was kind of the lone guy in town."

Sidney Poitier with American actors Spencer Tracy (1900 - 1967) and Katharine Hepburn (1907 - 2003). (Photo by Columbia Tristar/Getty Images)

Poitier peaked in 1967 with three of the year’s most notable movies: "To Sir, With Love," in which he starred as a school teacher who wins over his unruly students at a London secondary school; "In the Heat of the Night," as the determined police detective Virgil Tibbs; and in "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner," as the prominent doctor who wishes to marry a young white woman he only recently met, her parents played by Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in their final film together.

Theater owners named Poitier the No. 1 star of 1967, the first time a Black actor topped the list. In 2009 President Barack Obama, whose own steady bearing was sometimes compared to Poitier’s, awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, saying that the actor "not only entertained but enlightened ... revealing the power of the silver screen to bring us closer together."

CLASSIC HOLLYWOOD STAR ANN MILLER HAD 'NO REGRETS,' REMAINED HOPEFUL DURING CANCER BATTLE, PAL SAYS

His appeal brought him burdens not unlike such other historical figures as Jackie Robinson and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He was subjected to bigotry from whites and accusations of compromise from the Black community. Poitier was held, and held himself, to standards well above his white peers. He refused to play cowards and took on characters, especially in "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner," of almost divine goodness. He developed a steady, but resolved and occasionally humorous persona crystallized in his most famous line — "They call me Mr. Tibbs!" — from "In the Heat of the Night."

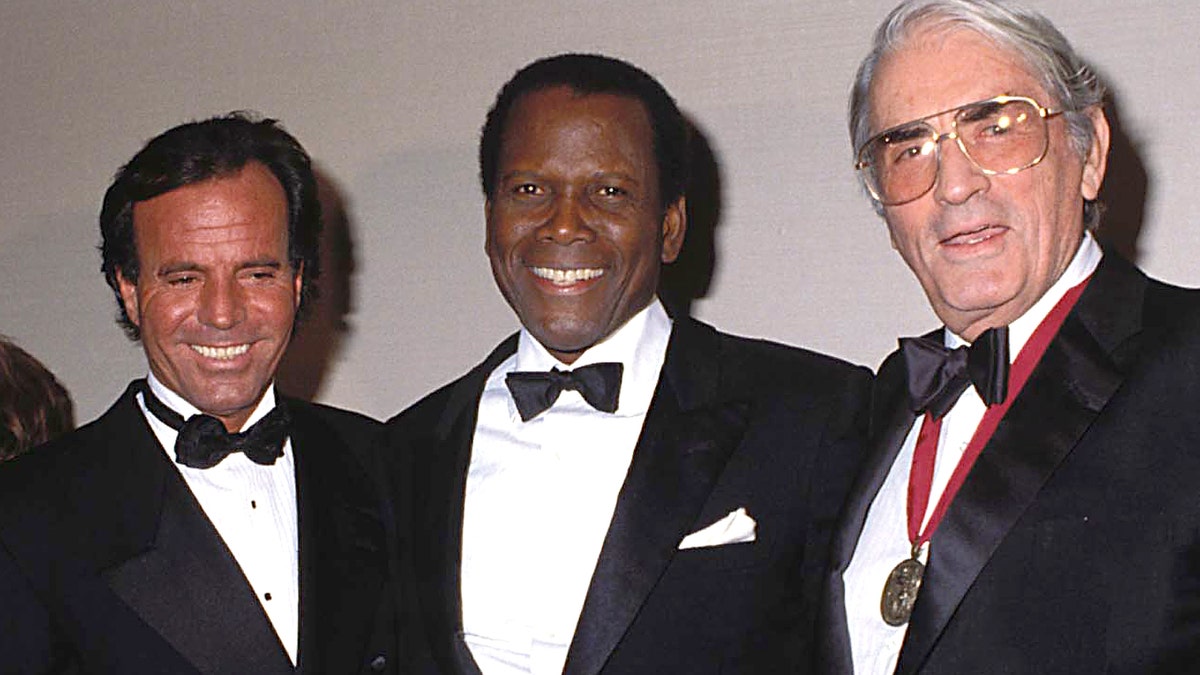

Sidney Poitier (center), seen here with Julio Iglesias (left) and Gregory Peck (right), was beloved by his peers. (Photo by Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic)

"All those who see unworthiness when they look at me and are given thereby to denying me value — to you I say, ‘I’m not talking about being as good as you. I hereby declare myself better than you,’" he wrote in his memoir, "The Measure of a Man," published in 2000.

But even in his prime he was criticized for being out of touch. He was called an Uncle Tom and a "million-dollar shoeshine boy." In 1967, The New York Times published Black playwright Clifford Mason’s essay, "Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?" Mason dismissed Poitier’s films as "a schizophrenic flight from historical fact" and the actor as a pawn for the "white man’s sense of what’s wrong with the world."

Stardom didn’t shield Poitier from racism and condescension. He had a hard time finding housing in Los Angeles and was followed by the Ku Klux Klan when he visited Mississippi in 1964, not long after three civil rights workers had been murdered there. In interviews, journalists often ignored his work and asked him instead about race and current events.

GENE KELLY’S DAUGHTER REACTS TO NEWS OF CHRIS EVANS IN TALKS TO PLAY ‘SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN’ STAR

American actor Sidney Poitier with his Oscar after he won the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role, at the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Hollywood, California, circa 1964. (Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images)

"I am an artist, man, American, contemporary," he snapped during a 1967 press conference. "I am an awful lot of things, so I wish you would pay me the respect due."

Poitier was not as engaged politically as Belafonte, leading to occasional conflicts between them. But he participated in the 1963 March on Washington and other civil rights events, and as an actor defended himself and risked his career. He refused to sign loyalty oaths during the 1950s, when Hollywood was barring suspected Communists, and turned down roles he found offensive.

"Almost all the job opportunities were reflective of the stereotypical perception of Blacks that had infected the whole consciousness of the country," he recalled. "I came with an inability to do those things. It just wasn’t in me. I had chosen to use my work as a reflection of my values."

Actor Sidney Poitier speaks at the Fulfillment Fund's Annual Stars Gala at the Beverly Hilton Hotel October 23, 2007, in Beverly Hills, California. (Photo by Michael Buckner/Getty Images)

Poitier’s films were usually about personal triumphs rather than broad political themes, but the classic Poitier role, from "In the Heat of the Night" to "Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner," was as a Black man of such decency and composure — Poitier became synonymous with the word "dignified" — that he wins over the whites opposed to him.

His screen career faded in the late 1960s as political movements, Black and white, became more radical and movies more explicit. He acted less often, gave fewer interviews and began directing, his credits including the Richard Pryor-Gene Wilder farce "Stir Crazy," "Buck and the Preacher" (co-starring Poitier and Belafonte) and the Bill Cosby comedies "Uptown Saturday Night" and "Let’s Do It Again."

In the 1980s and ’90s, he appeared in the feature films "Sneakers" and "The Jackal" and several television movies, receiving an Emmy and Golden Globe nomination as future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall in "Separate But Equal" and an Emmy nomination for his portrayal of Nelson Mandela in "Mandela and De Klerk." Theatergoers were reminded of the actor through an acclaimed play that featured him in name only: John Guare’s "Six Degrees of Separation," about a con artist claiming to be Poitier’s son.

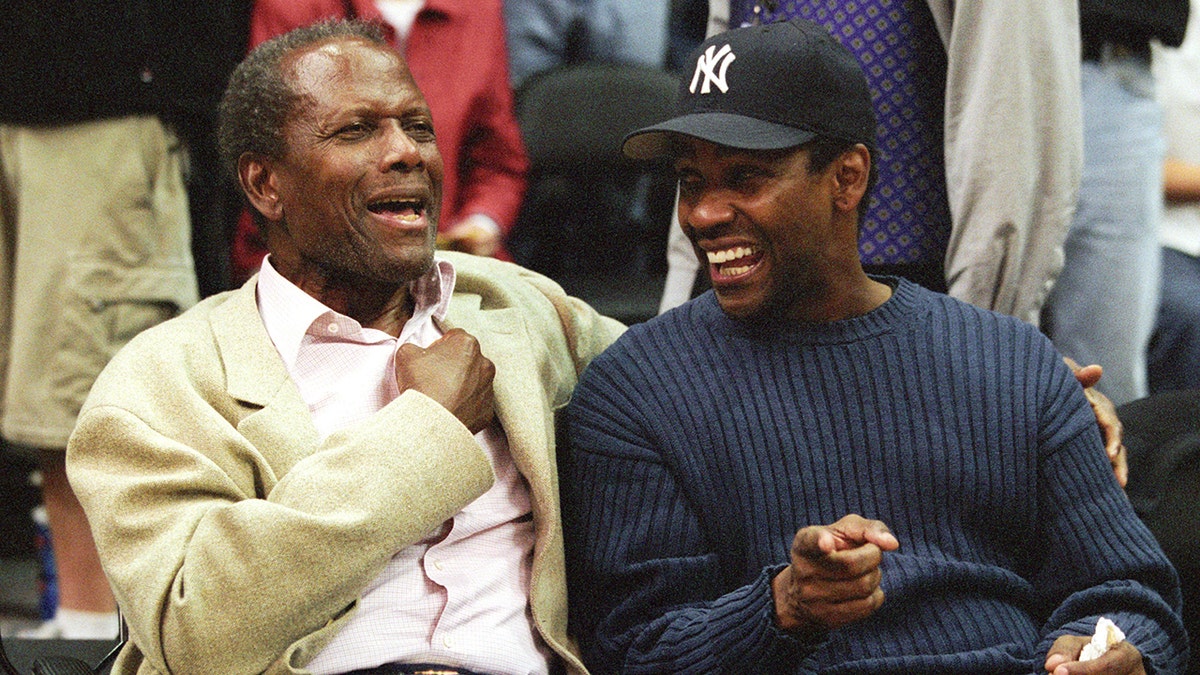

Sidney Poitier and Denzel Washington. (Photo by Kevin Reece/WireImage)

In recent years, a new generation learned of him through Oprah Winfrey, who chose "The Measure of a Man" for her book club. Meanwhile, he welcomed the rise of such Black stars as Denzel Washington, Will Smith and Danny Glover: "It’s like the cavalry coming to relieve the troops! You have no idea how pleased I am," he said.

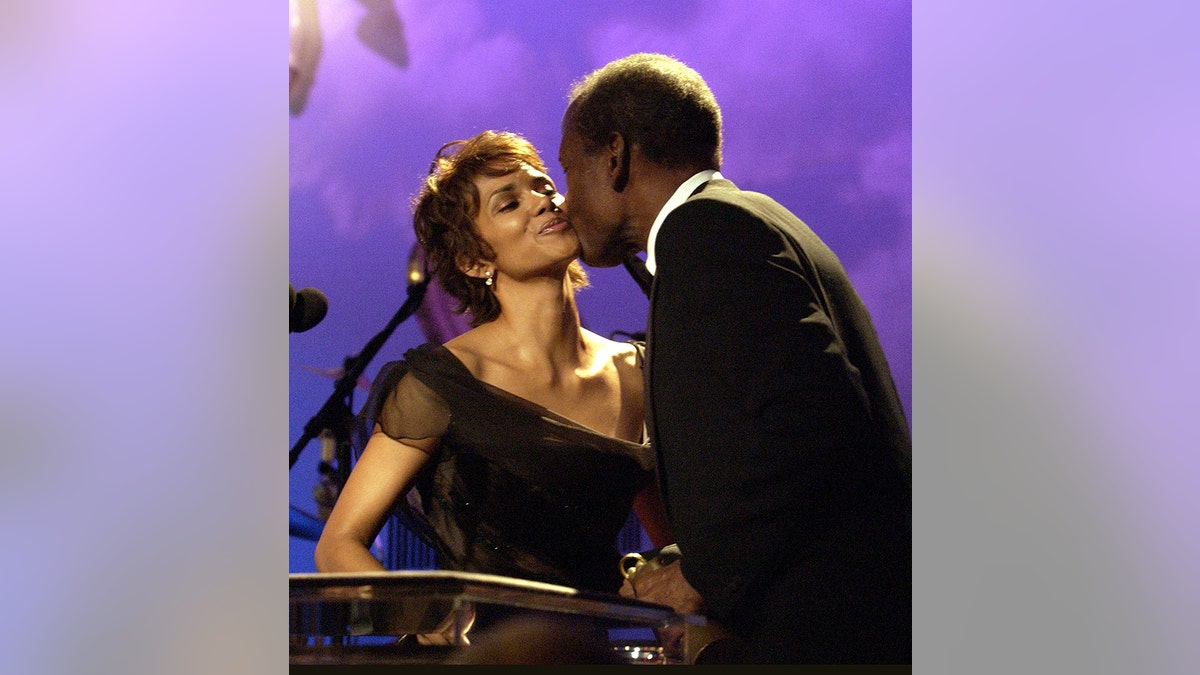

Poitier received numerous honorary prizes, including a lifetime achievement award from the American Film Institute and a special Academy Award in 2002, on the same night that Black performers won both best acting awards, Washington for "Training Day" and Halle Berry for "Monster’s Ball."

JOELY FISHER GETS CANDID ON FORGIVING LATE DAD EDDIE FISHER: 'I ADORED HIM'

"I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney," Washington, who had earlier presented the honorary award to Poitier, said during his acceptance speech. "I’ll always be following in your footsteps. There’s nothing I would rather do, sir, nothing I would rather do."

Poitier had four daughters with his first wife, Juanita Hardy, and two with his second wife, actress Joanna Shimkus, who starred with him in his 1969 film "The Lost Man." Daughter Sydney Tamaii Poitier appeared on such television series as "Veronica Mars" and "Mr. Knight."

Halle Berry presents an award to Sidney Poitier during The 15th Carousel Of Hope Ball - Show and Audience at Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills, California, United States. (Photo by M. Caulfield/WireImage)

The only Black actor before Poitier to win a competitive Oscar was Hattie McDaniel, the 1939 best supporting actress for "Gone With the Wind." No one, including Poitier, thought "Lilies of the Field" his best film, but the times were right (Congress would soon pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, for which Poitier had lobbied) and the actor was favored even against such competitors as Paul Newman for "Hud" and Albert Finney for "Tom Jones." Newman was among those rooting for Poitier.

When presenter Anne Bancroft announced his victory, the audience cheered for so long that Poitier momentarily forgot his speech. "It has been a long journey to this moment," he declared.

Poitier never pretended that his Oscar was "a magic wand" for Black performers, as he observed after his victory, and he shared his critics’ frustration with some of the roles he took on, confiding that his characters were sometimes so unsexual they became kind of "neuter." But he also believed himself fortunate and encouraged those who followed him.

Actor Sidney Poitier speaks on stage at the YWCA Greater Los Angeles Rhapsody Ball held at the Regent Beverly Wilshire Hotel on November 14, 2014, in Beverly Hills, California. (Photo by Tommaso Boddi/WireImage)

"To the young African American filmmakers who have arrived on the playing field, I am filled with pride you are here. I am sure, like me, you have discovered it was never impossible, it was just harder," he said in 1992 as he received a lifetime achievement award from the American Film Institute. "

"Welcome, young Blacks. Those of us who go before you glance back with satisfaction and leave you with a simple trust: Be true to yourselves and be useful to the journey."

The Associated Press contribued to this report.