To the world, Rita Hayworth was a fiery-haired love goddess who captivated audiences on the big screen with a single slip of a satin glove, served as one of America’s favorite pinups during World War II and kept Fred Astaire on his toes — but to Princess Yasmin Aga Khan, she was just mom.

The actress, who would have turned 100 on October 17, passed away in 1987 in her New York City apartment at age 68 from Alzheimer’s disease. Her youngest daughter has since founded the annual Rita Hayworth Gala through the Alzheimer’s Association to keep her mother’s legacy alive, all while raising funds to support studying the disease in hopes of finding a cure.

The 2017 event raised $2 million and a grand total of over $75 million. The 35th annual gala takes place on October 23 in New York City.

But to Khan, 68, presiding over the gala continues to be bittersweet.

“She was just a wonderful mother,” Khan told Fox News. “So loving, so caring. I still have vivid memories of her. I remember being on the set of 'Pal Joey' with Frank Sinatra and just how I was in awe of her. And just the excitement of 'Circus World' with John Wayne. But I just remember her as a loving, loving mother.”

After Hayworth’s marriage to Orson Welles came to an end in 1947, the actress married Prince Aly Khan in 1949. Yasmin was born that same year. And while the couple called it quits in 1953, Khan revealed they remained on good terms.

“I would visit my father and spend the summers with him in the south of France,” she recalled. “They had a good relationship after their divorce, so that was helpful. There weren’t any bad feelings.”

Living with a movie star in Beverly Hills during the rest of the year wasn’t always glitz and glamour. Khan recalled how surprisingly normal it was to live with one of the most famous women in the world.

Prince Aly Khan (1911 - 1960) at Epsom races with his wife, Hollywood actress Rita Hayworth (1918 -1987). (Getty)

“She really taught me important things, such as taking care of my room, making my bed and making sure my clothes were off the floor,” Khan chuckled. “I would ride the golf cart with her because she was golfer. And at home, she would put on music and play the castanets. … I had a wonderful childhood.”

But by the time Khan was in high school, she started noticing there was something odd with her mother, who was in her early 50s. Khan, who was in boarding school in Massachusetts while her mother was filming in Hollywood, picked up on some peculiar behavior when Hayworth would call in to check on her.

“I just noticed that in some phone calls, she was slightly off and repetitive,” recalled Khan. “I didn’t understand it. And then I would go home and find the same thing. Repetition, a bit of paranoia, hearing things that weren’t there. And then hitting the panic button for the police. It started slowly back then. And that would be in the ‘60s."

Hayworth’s symptoms continued when Khan headed off to Bennington College in Vermont.

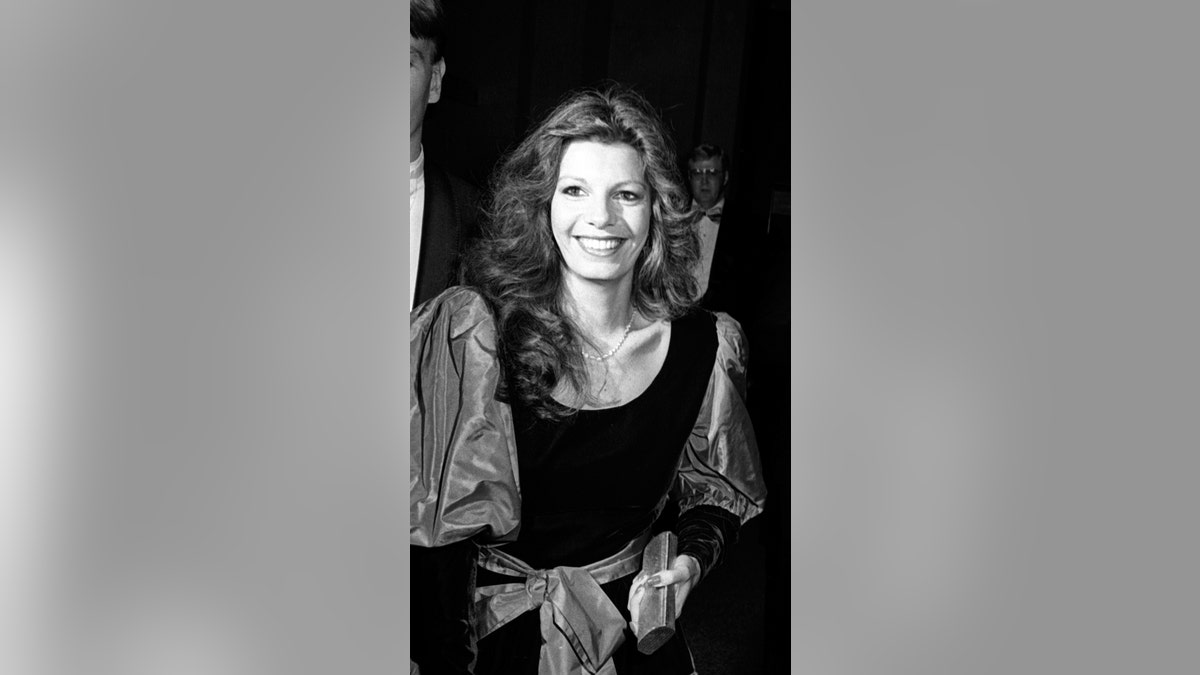

Princess Yasmin Aga Khan in 1983. (Getty)

“She would become more repetitive,” said Khan. “… I found it really odd. … I didn’t understand it. … She would say to me, ‘I can’t remember’ and laugh it off.”

The New York Times reported that in 1971, Hayworth attempted a stage career, which ended abruptly because she was unable to remember her lines. Her last film was 1972’s “The Wrath of God.”

And then Hayworth endured what Khan described as “a total collapse.” People Magazine reported that in 1976, the press wrote about Hayworth getting off a plane in London “drunk, agitated and confused.”

The New York Times added that in 1981, a court in Los Angeles declared Hayworth was legally unable to care for herself. Khan stepped in and became Hayworth’s conservator. She brought her mother to New York City and lived right next door to her with the help of nursing care.

Rita Hayworth in 1978.

“It was something natural,” she said. “She was so sweet and loving. My motherly instincts just took over. It was a natural thing for me to help her and go through this with her.”

It wouldn’t be until 1981 that Hayworth was finally diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Dr. Ronald Fieve at New York’s Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center suspected Hayworth had the disease, despite the star’s hesitation in getting a CT scan.

The news made Khan feel both relieved and devastated.

“By the time she was diagnosed, she really wasn’t totally aware,” said Khan. “But it was difficult. … She would look at me and say, ‘Who are you?’ That was heartbreaking. … She would get angry for no reason. And belligerent. Not all people with dementia get that way, but she did. … I had to regulate her medication as she became more aggressive. … And just the basics of eventually trying to get her in the shower. It was very painful.”

Rita Hayworth sitting on a sofa with her young daughters, Rebecca Welles (left) and Yasmin Khan, in her lap. (Getty)

Khan credited the Alzheimer’s Association, which at the time was “a mom and pop organization,” for being by her side as she further educated herself on the disease, all while losing her mother to it.

The Alzheimer’s Association was founded in 1980 by a group of family caregivers seeking support to cope with an illness that was seemingly unheard of during the time. It’s founding president, Jerome H. Stone, helped launch the association after his wife Evelyn was diagnosed in 1970.

Khan said that after news broke of her mother’s condition, it was Stone who reached out to offer a helping hand.

“They found me and said, ‘We have this small organization and we would love for you to be a part of it,’” said Khan. “‘We can share our heartache and our pain and also, what’s coming next. Preparation of the disease and what to expect down the road.’ I dealt with it all because I had a group of family members, which was the Alzheimer’s Association. They were there for me. I was able to talk to those family members. And we could share our issues. It was wonderful.”

Rita Hayworth in 1942. (Getty)

Hayworth pursued her passions for oil painting, playing the castanets and golfing. But with no cure for Alzheimer’s, the disease progressed.

“From the middle stage to the end, it took about maybe 4-5 years,” said Khan. “When she was near death… I called in the priest for her last rites. And then she lived another two years. Her heart was so strong, but she really didn’t recognize anyone. It was a slow decline. She had wonderful care.

“She was right next door, right next to me. I could go in and talk to her in her ear. I always felt like I had to communicate. Maybe somewhere she would hear me. And then my son was born in 1985. I would bring him in and talk to her. I wasn’t sure if she knew or not, but I thought it was important to be there and share because one never knows.”

Khan testified before a Congressional committee in 1983 in an effort to raise funds for Alzheimer’s research, declaring the disease had reduced her mother to “a state of utter helplessness.”

Rita Hayworth in her later years. (AP)

While Khan was eager to raise awareness on the illness, she wished someone in Hollywood would have joined her in speaking out.

“It was a bit frustrating because it was covered, but not as much as it should have been covered back then by the media,” she explained. “… I think it was disappointing to me that someone in Hollywood didn’t step up and take the cause, like Elizabeth Taylor with AIDS. It’s been a long road. And now the press writes about it… Every country is affected by the disease.”

The crusade continues for Khan.

“Just having the experience of a loved one with the disease, and seeing the decline and knowing so many people have [it]… That motivates me,” said Khan. “I’m hoping that we find the answers in my lifetime. … That’s been my motivation. We need to find a cure.”

And the memories of living – and loving Hayworth – have simply never left Khan.

“She was just the most wonderful mother,” said Khan. “She loved working with Fred Astaire — she would talk about working with him… She introduced tennis and golf to me. And she loved her work. I knew she was famous, but she was my mom, a regular mom. … It’s a sad story. It’s a sad disease.”