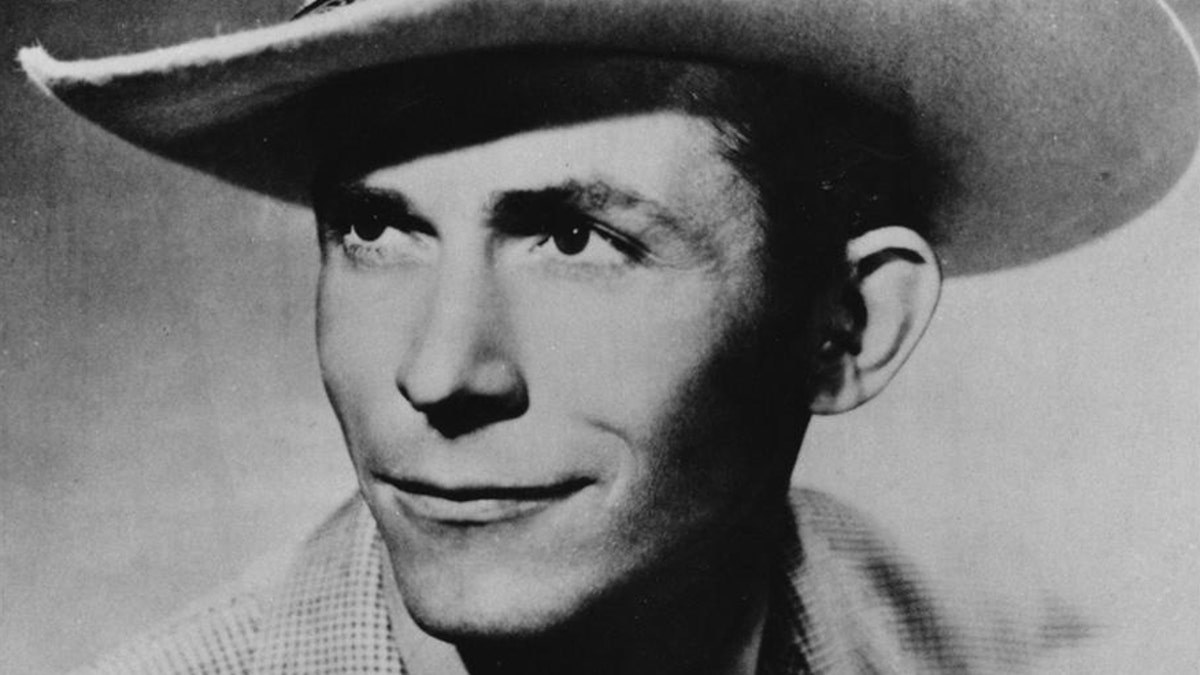

** FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE--FILE **This is an undated file photo of Country and Western singer and guitarist Hank Williams. He was born in Georgiana, Al., in 1923 as Hiram King Williams, and he died of a heart attack in 1953. (AP Photo/FILE)

The new biopic “I Saw the Light,” in theaters Friday, traces country legend Hank Williams’ struggles with alcohol, infidelity — and the weight of being one of the biggest music stars in the United States, following hits such as his cover of “Lovesick Blues” (1949) and his own “Why Don’t You Love Me” (1950).

But one big thing is left out of the movie: the singer’s mysterious death. It was something he apparently saw coming. On the evening of December 30, 1952, the restless, rail-thin 29-year-old tossed and turned in bed at his home in Montgomery, Ala. When new wife Billie Jean asked what was the matter, she claimed his reply was, “I think I see God comin’ down the road.”

Within 48 hours of Williams’ prediction, he had met his maker, but the circumstances surrounding how he died have given rise to one of music history’s greatest debates.

“I think he had a profound sadness in him,” says Marc Abraham, writer and director of the new biopic. “Tom [Hiddleston, the actor portraying Williams] puts across that impending sense of doom. Hank felt there was something bad around the corner.”

There is a framework of events that is largely agreed upon, starting with Williams being chauffeured to a planned New Year’s Eve show in Charleston, W. Va. The singer, who suffered from a back problem, was given a sedative by his regular doctor — who had allegedly purchased a fake medical diploma through the mail and was rumored to frequently overprescribe — before setting off with a college student named Charles Carr acting as his driver. But inclement weather meant they couldn’t get to Charleston, so the concert was canceled and they instead made a pit stop at the Andrew Johnson Hotel in Knoxville, Tenn.

Williams had already been drinking when he was given a shot of B12 and morphine by the hotel doctor. Just before midnight, Carr set about getting Williams to a planned New Year’s Day show in Canton, Ohio. Most accounts have Williams looking and sounding groggy, and hotel porters allegedly had to carry him to the car. About six or seven hours later, on the morning of Jan. 1, 1953, Carr realized his passenger was dead and already beset with rigor mortis. When the singer’s death was announced to the waiting crowd at the Palace Theatre in Canton, they sang Williams’ “I Saw the Light” in unison.

But suspicions about this final journey arose immediately. Officials listed his cause of death as heart failure but noted that body contusions meant he had recently been in a fight. At the time, Carr’s nervous account of the final few hours of the journey were enough to raise questions of foul play, especially when some witnesses — including a police officer — claimed to have, oddly, seen a soldier also riding in the car.

Some biographers (including Colin Escott, whose book “I Saw the Light” provides the basis for the film) have suggested that Williams may have even died at the Andrew Johnson in Knoxville, and that Carr had unwittingly driven several hundred miles with a corpse. It was also something that was suggested by the initial police report. (Carr died in 2013 and, for much of his life, kept silent on his journey with Williams.)

But as Jack Neely, executive director of the Knoxville History Project explains, local folklore tells a different story. “In recent years, a Knoxvillian . . . has been telling people he was the doorman at the Andrew Johnson, and he says Hank was conscious and joking when he left.” Carr had insisted that Williams couldn’t have been dead in Knoxville, because they had spoken briefly in the car after leaving town.

Local lore also places Williams at a Knoxville hospital getting a second shot of morphine — this in addition to the one administered by the hotel doctor — that might have caused a drug overdose.

There’s so much conjecture that both “I Saw the Light” and the 1964 biopic, “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” chose to avoid depicting the final journey altogether. “I actually wrote 13 pages for that scene but took them out because they felt superfluous,” explains Abraham. “To have a kid [Carr] turn around, feel his pulse and realize [Williams] was dead, it felt anticlimactic.”

Besides, Neely adds, “No matter which account you pick, there are going to be people who say, ‘That’s not how it happened.’ ”