Oldest-living Rosie the Riveter talks her place in history

The oldest-living Rosie the Riveter, Elinor Otto, talked to Fox News about how she didn’t think she was doing anything remarkable until others told her she and her fellow Rosies were trailblazers for women in the workplace.

America’s longest-working Rosie the Riveter is getting ready for her close-up.

Fox News confirmed two Hollywood film producers are interested in possibly making a documentary on the life of Elinor Otto, 98. An announcement is expected to be made on National Rosie the Riveter Day on March 21.

Celebrities that have been raising awareness about the contributions made by the World War II generation including Scarlett Johansson, Tom Selleck and Norman Lear, among others.

Otto is scheduled to meet with Lear, 95, to enlist his support for the Rosie the Riveter Memorial Rose Gardens campaign. The iconic TV producer/writer flew 53 missions during WWII in a B17 bomber that was built by Rosies.

Elinor Otto supporting the Rosies today. (Spirit of '45)

Otto was nearly scouted as an actress before she built airplanes as one of the first women to step forward during WWII to do the jobs vacated by men who were called into service. She told Fox News she never had an interest in becoming a screen siren.

“I had no desire to ever be in the entertainment business. No desire at all,” said Otto. “They wanted me to be an extra. I didn’t even want to do that. I wasn’t really excited. I don’t know why. Just wasn’t. I loved movies, but I just didn’t want to be in them. I was too shy.”

The single mother, who joined Rural Aircraft Corporation at age 22 in January 1942, simply wanted to be put to good use – even if she didn’t instantly get support from her colleagues.

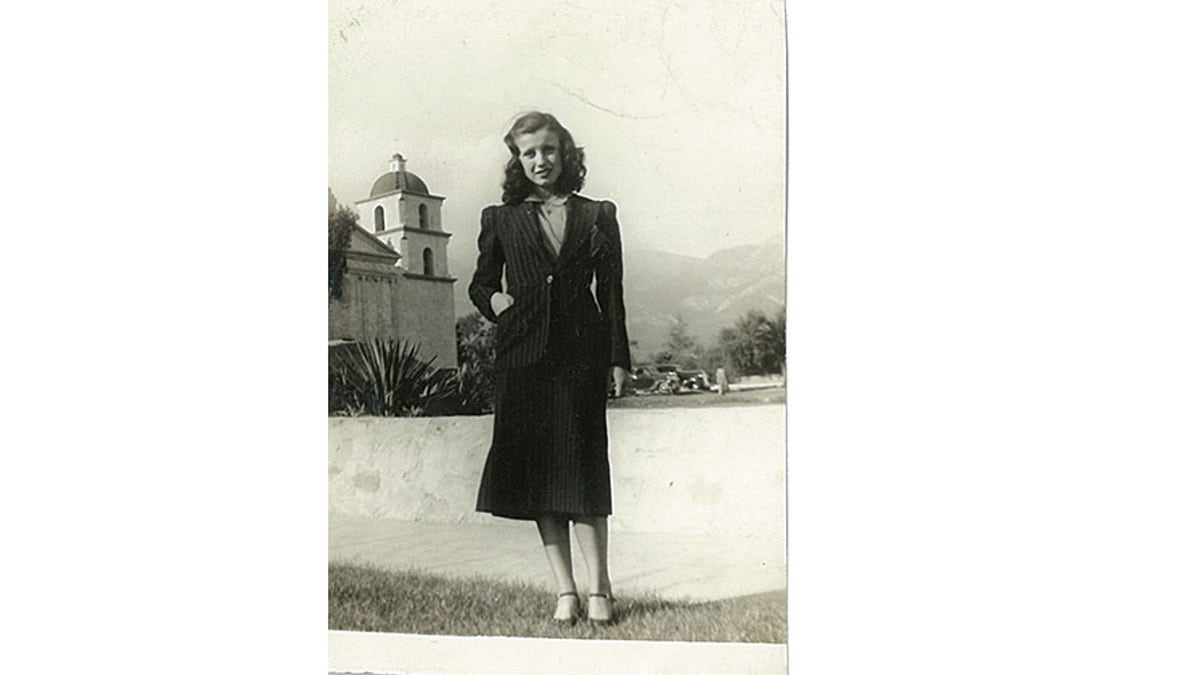

Elinor Otto in the '40s. (Courtesy of Elinor Otto)

“Doing those airplanes and working with men – that was exciting because I’d never done that before,” she explained. “And it was a challenge to us women. It was a great challenge because we didn’t know how to work with the tools. And of course, we were so busy with schedules during the War, we didn’t have time for school. So, the job training came working with men.

"At first, the men didn’t want us to come in there and work with them. They thought they couldn’t take their shirts off, they couldn’t smoke. But after we proved ourselves and showed we wanted to learn right away, they became very nice to us… We knew this War had to be won.”

The female war workers of the 1940s were symbolized in the iconic 1943 Rosie the Riveter poster produced by J. Howard Miller, which was briefly displayed in Westinghouse Electric Corporation factories in California.

Rosie the Riveter (Getty)

The image, which represented the millions of women entering America’s factories, plants and shipyards, is now recognized as a national symbol of female patriotism.

Otto insisted at that time, their efforts weren’t recognized as anything of significance. It was just another day at work to help raise her family.

“I don’t think we thought of it as anything special,” she said. “It was just something we had to do. And of course, when the war ended, the men came back for their jobs. We just left and some of those lucky men were able to return and take their jobs back. Nobody ever called us Rosies.

"Nobody ever thought we did anything special. Nothing at all. And we didn’t either. We forgot all about it. We were part of the war effort, that’s all we knew. But decades later, they now tell us we helped pave the way for women. We showed women they were able to do things they didn’t think they could do before.”

Elinor Otto in the '40s. (Courtesy of Elinor Otto)

And joining the war effort was no easy task for the young mother, who was determined to put food on the table for her young son.

“It was hard, financially,” she admitted. “We were just happy to get a steady paycheck — 65 cents an hour! You couldn’t even live off that now… But it was a gratifying experience… All of these women came from different states to work… We all got together and worked as hard as we could.

"And I remember you couldn’t even get silk hose [stockings] in those days. You had to head down to Tijuana. But none of those things from Tijuana lasted very long. They fell apart after you washed them!”

But Otto said she and the other “Rosies” relied on music played on loudspeakers in the factories to keep their morale up.

Elinor Otto (right) with her sister. (Courtesy of Elinor Otto)

“It helped a lot,” said Otto. “Especially when you’re riveting and making noise!”

On their days off, the women would catch big bands on tour where they danced for hours, go on dates or just give their jumpsuits a break for glamorous dresses. But when the war came to an end in 1945, Otto refused to go back to the life she once lived before. She just wanted to work.

“I worked in an office and I was a typist,” said Otto. “I didn’t like that. I didn’t like just sitting around. I prefer to be on my feet and run around with my energy. I tried car hopping… That was a lot of fun. Got a lot of tips… But when they put us on skates, I left. I didn’t want to walk around carrying trays of on skates and drop the food to the floor!”

Otto moved on to Ryan Aeronautical Co. in San Diego in 1951, which build “The Spirit of St. Louis,” the monoplane flown by Charles Lindbergh in 1927 on the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris. Otto helped build airplanes again for 14 years until she was laid off.

Elinor Otto riveting. (Spirit of '45)

Then nearly a year later, Otto was hired to work in Douglas Aircraft in Long Beach, which was hiring women for the first time since the war. The factory closed down in 2015. Otto still owns the last rivet gun she used on the job.

“I will never say I’m retired!” insisted Otto. “We were just laid off. No retirement for me… But my family keeps me busy now. And I’m always surrounded by young people… I like to cook fresh food. I also go visit people, write letters. I try to do the best I can.”

Otto is surprised there would be any interest in her life story.

“We just thought we did what we were supposed to do,” said Otto. “We did our duty, but we didn’t think how it important it was like it seems to be now… I always tell young people, we made history. Now it’s your turn. And there’s a lot of technology now. We need the new technical Rosies… Seriously, you can do it. Never give up.”

And at her age, Otto said she’s just as energetic and eager to inspire other women looking to make a difference for their country.

Elinor Otto with young girls today. (Spirit of '45)

“I’ve always been a hard worker and I’m proud of that,” said Otto. “Age doesn’t always matter… And people are still surprised that life goes on after 63. It does!”