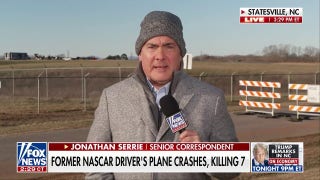

(University of Maryland)

While electric-car advocates may avoid the issue, some buyers simply won't choose a plug-in car that can't travel unlimited distances.

That's where the Chevy Volt-style range extender comes in, though the Volt adds unlimited range by burning gasoline in a conventional engine to generate electric power.

Now a new type of fuel cell offers the potential for a different kind of range extender, one that removes the enormous practical problem facing hydrogen fuel cells: the lack of a distribution infrastructure to fuel vehicles that require pure hydrogen to feed their fuel cells.

Smaller, cooler solid-oxide fuel cells

The new technology, according to Tech Review, improves on the known designs for fuel cells with solid ceramic electrolytes. These solid-oxide fuel cells, already in small-scale use for stationary applications in buildings, have historically been both bulky and extremely hot--operating at up to 900 degrees Centrigrade.

Researchers at the University of Maryland have managed to shrink the size and lower the operating temperature of a solid-oxide fuel cell by a factor of 10, meaning it could conceivably produce as much power as a car engine but occupy less space.

The advances come from new materials for the solid electrolyte, as well as design changes, and the researchers feel they have further avenues for improvement left to explore. They have already lowered operating temperature to 650 degrees C, and their goal is 350 degrees C--making vehicle use much more practical.

Best of all, solid-oxide cells can run on any variety of fuel feedstocks, including gasoline, diesel, natural gas, and propane.

Perfect as range extender

While not suited for frequent on/off cycles, fuel cells are neatly matched to the demands of an electric-car range extender, which provides a steady flow of electricity to a battery-operated vehicle. The battery pack copes with the highly variable power demand, while the fuel cell recharges the pack at a steady rate in the background.

The promise of the new technology is indicated by the fact that research leader Eric Wachsman (he runs the Energy Research Center at the University of Maryland) is now forming a company to commercialize the technology, which has been partially funded by the U.S. Department of Energy.

As with all such research, it will take many years before it's clear whether the new fuel cell design can be reliably produced in bulk and at a cost that makes it practical for the uses Wachsman envisions.

Twice as many miles from 1 gallon

But internal combustion engines only transform a quarter of the energy content of gasoline into torque to a car's wheels. The new design could, theoretically, double that figure.

And if it does, it solves at one fell swoop the fuel-distribution problem that has bedeviled the prospects for hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles to date.

As we wrote more than two years ago, while electric cars are being launched by virtually every major carmaker, hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles face a host of challenges.

Hydrogen's challenges

Those include an utter lack of distribution infrastructure for vehicle fueling, and a questionable "wells-to-wheels" carbon footprint that depends great on the source of the large amount of energy needed to create pure hydrogen.

With more than 15,000 plug-in cars added to U.S. roads this year alone, grid electricity will be an increasingly practical way to power shorter trips.

A decade of hydrogen vehicle development has produced perhaps a few hundred, including a couple of hundred "Project Driveway" Chevrolet Equinox Fuel Cell conversions and a few dozen Honda FCX Clarity models.

For longer trips, we may be stuck with gasoline. It's flammable, possibly carcinogenic, and causes a quarter of a million car fires a year.

But it's out there nonetheless, and if transforming it chemically inside a fuel cell to release its energy proves to be cleaner and more efficient than blowing it up in a combustion engine, that can only be to the good.