As politicians in America and across the globe lined up last week to condemn President Trump’s reported remarks calling certain African nations “s---hole countries,” there was a somewhat muted response in Europe -- a sign of how the political winds of immigration are blowing.

Europe is a continent filled with leaders happy to speak out in condemnation of the U.S. president, but the silence last week was noticeable -- with the New York Times describing a “ringing silence across broad parts of the European Union, especially in the east, and certainly no chorus of condemnation.”

But a continent spooked by a populist revolt still bubbling in its parliaments and roaring on its streets, many of Europe’s politicians are still struggling with an influx from developing countries, or fighting for their political lives as they fend off challengers running on doing just that.

Europe has been wracked by a continent-wide migration crisis since 2015, when German Chancellor Angela Merkel threw open Germany’s borders to a wave a Syrian refugees -- telling Germans: “Wir schaffen das!” [We can do this]

Germany

While Merkel was applauded worldwide - and immediately given Time’s Person of the Year - refugees and economic migrants from other countries, along with a wave of terror attacks and other crimes and social problems, flooded into the continent. Merkel’s poll numbers caved, and she was forced to shift right to appease the anti-migrant sentiments.

In December 2016, she pushed for a so-called “burqa ban” and promised that the 2015 migration surge “cannot, should not and must not be repeated.”

Her Christian Democrats (CDU) nonetheless took a hit in September’s national elections, while the anti-migration Alternative for Germany (AfD) surged, and the woman described just a few years ago as the “chancellor of the Free World” was left fighting for her political life. Her party now looks to convince reluctant former coalition partners, the left-wing Social Democrats (SPD), to form another coalition and keep her in power.

An initial draft of a potential coalition deal includes a hard cap of approximately 200,000 refugees a year -- a significant decrease from the more than a million refugees that flooded into the country in 2015 -- a sign that migration will be a decisive factor in whether Merkel survives.

Eastern Europe

Other countries, particularly in Eastern Europe, have been taking a strong line of migration for years. Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary have been particularly muscular in asserting their own sovereignty in dealing with immigration issues -- despite opposition from E.U. officials.

Hungary has erected a border fence amid a host of border security measures -- and even had the Trumpian chutzpah to ask the E.U. to pay for half of it. For pro-open borders left, outspoken Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has become their bogeyman, using language that makes Trump’s appear almost timid.

In an interview with Germany’s Bild, this month, Orban referred to some migrants “Muslim invaders,” and called multiculturalism “an illusion.”

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has built a border fence and asked the E.U. to pay for half of it. (AP)

“If you take masses of non-registered immigrants from the Middle East into your country, you are importing terrorism, crime, anti-Semitism, and homophobia,” he said in a follow up interview this week.

Orban also made reference to the mass sexual assaults on New Years’ Eve 2015 in Cologne, Germany, as well as other problems attributed to the wave of migration from Africa and the Middle East.

“[In Hungary] there are no ghettos and no no-go areas, no scenes like New Year's Eve in Cologne. The images from Cologne have deeply moved us Hungarians,” he said. “I have four daughters. I can not help my children grow up in a world where something like Cologne can happen.”

While Orban is perhaps the most outspoken of Europe’s political leaders, other more moderate leaders are tilting in Orban and Trump’s direction.

France, United Kingdom

Europe’s establishment breathed a sigh of relief in May, when French centrist Emmanuel Macron comfortably beat right-wing and anti-migration Marine Le Pen in France’s presidential election. Macron’s comfortable win was seen by many analysts as a sign that the seemingly unstoppable 2016 populist wave, which gave the world Brexit and President Trump, was finally crashing upon the rocks.

But Macron has rejected an open-arms approach to migration, attempting to find himself a middle ground between Merkelism and Orbanism. In a New Year’s Eve speech, he admitted: “We can’t welcome everyone, and we can’t work without rules.”

French President Emmanuel Macron has come under fire for taking a tougher stance on economic migrants. (AP)

His government has also taken a tougher line on economic migrants, opening himself up to criticism from his own party, who have accused him of being too tough and catering to the right-wing. According to Reuters, opponents point to a new bill that would increase detention times and lead to the deportation of anyone not classified as a refugee from a warzone.

But Macron followed this up Tuesday with a visit to the former “Jungle camp” at Calais -- a sprawling refugee camp at the port to the United Kingdom that was deconstructed in 2016.

In a speech at the site of the former camp on Tuesday, he promised to be sure it did not return. In a meeting on Thursday with British Prime Minister Theresa May, he is expected to demand a renegotiation of the border arrangement with the U.K., including more money from the British and for them to take on more refugees.

That push is unlikely to be well-received in the U.K., where the decision to leave the European Union was largely motivated by migration-related issues and a need to take control of borders.

In 2016, Britain allowed in child asylum seekers from Calais who had family members in the U.K. But outrage and mockery followed when pictures appeared in British newspapers showing what one Conservative MP described as “hulking young men” presenting themselves as children.

Former U.K. Independence Party leader Nigel Farage said this week that France’s migration problems are France’s to solve and that Macron should stop playing hot potato.

“If they are illegal immigrants, France should get rid of them, if they are people claiming refugee status, France should process them,” Farage said in an interview with the BBC. “It’s actually desperately simple but the French don’t want to do that and the truth of it for the last 10, 15, 20 years the French have been quite happy for camps to develop and for people to climb on the back of lorries to go to England, and then it’s our problem.”

Austria

A key motivator for many Western European politicians are impending elections. While Merkel is scrambling for survival in Germany, across the border in Austria, a right-wing government was formed in December led by the 31-year-old Sebastian Kurz -- whose center right People’s Party (OVP) campaigned primarily on a tough stance on migration, and formed a coalition with the far-right Freedom Party (FPO).

Austria will take over the presidency of the E.U. Council in the summer, and Kurz said in an interview published Wednesday one of his top priorities will be “border control to stop illegal migration to Europe.”

But far from looking for conflict, Kurz told German newspaper FAZ that the continent’s view on migration is now much closer to his own.

Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz met with his German counterpart Angela Merkel this week. (AP)

“There has been a lot of movement in recent years. For example, the German position is now much closer to ours than it was two years ago,” Kurz said. “Many states have moved in the right direction. Now we need a focus on proper protection of the external borders of the EU and not just the constant debate about the distribution of refugees within the European Union by quotas.”

As Austria turns rightward, and Germany struggles to form a government, all eyes will soon move to Italy, where voters will go to the polls in March in an election dominated by discussions about the E.U. and migration.

Italy

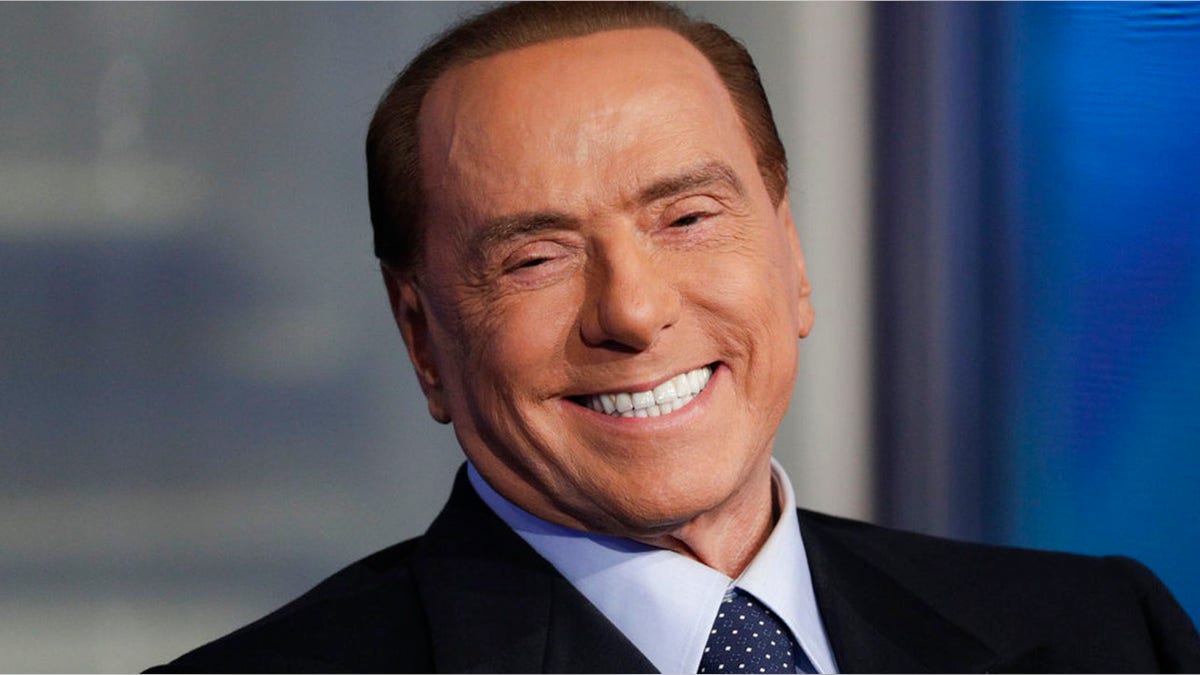

There, the populist Five Star Movement leads the polls, although its reluctance to form a coalition (and with it polling at approximately 27-30 percent) the most likely outcome appears to be a right-wing coalition led by former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party. While Forza is a relatively moderate right-wing party, its path to government lies in a coalition with further right parties, including the Northern League -- which has campaigned strongly for control of migration flows into the country.

Yet even current left-wing Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni’s government is far from an open borders free-for-all. Gentiloni’s cabinet includes Interior Minister Marco Minniti who has been credited with overseeing a massive drop in migrants into Italy from Libya by striking controversial deals with the Libyan government to strengthen security and the Coast Guard in the Mediterranean.

Former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia look likely to form a coalition after Italian elections in March. (AP)

Humanitarian groups are seeing these debates play out on the ground too. The Washington Post offered a glimpse into a refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos, where migrants wait in limbo to be shipped back via a deal signed between the E.U. and Turkey in 2016.

“The first thing you notice is the smell: the stench from open-pit latrines mingling with the odor of thousands of unwashed bodies and the acrid tang of olive trees being burned for warmth.

Then there are the sounds: Children hacking like old men. Angry shouts as people joust for food,” the Post reports.

Humanitarian groups have expressed concern for squalid conditions at refugee camps on Greek islands. (Reuters)

Looking for answers as to why the once welcoming E.U. is keeping migrants in horrific conditions, activists on the ground told the Post that they believe it’s part of the new change in tone, with European leaders sending a message to potential migrants.

Eva Cossé, a researcher for Human Rights Watch, told the Post that the message was simple: “‘Don’t come here, or you’ll be stuck on this horrible island for the next two years.’”