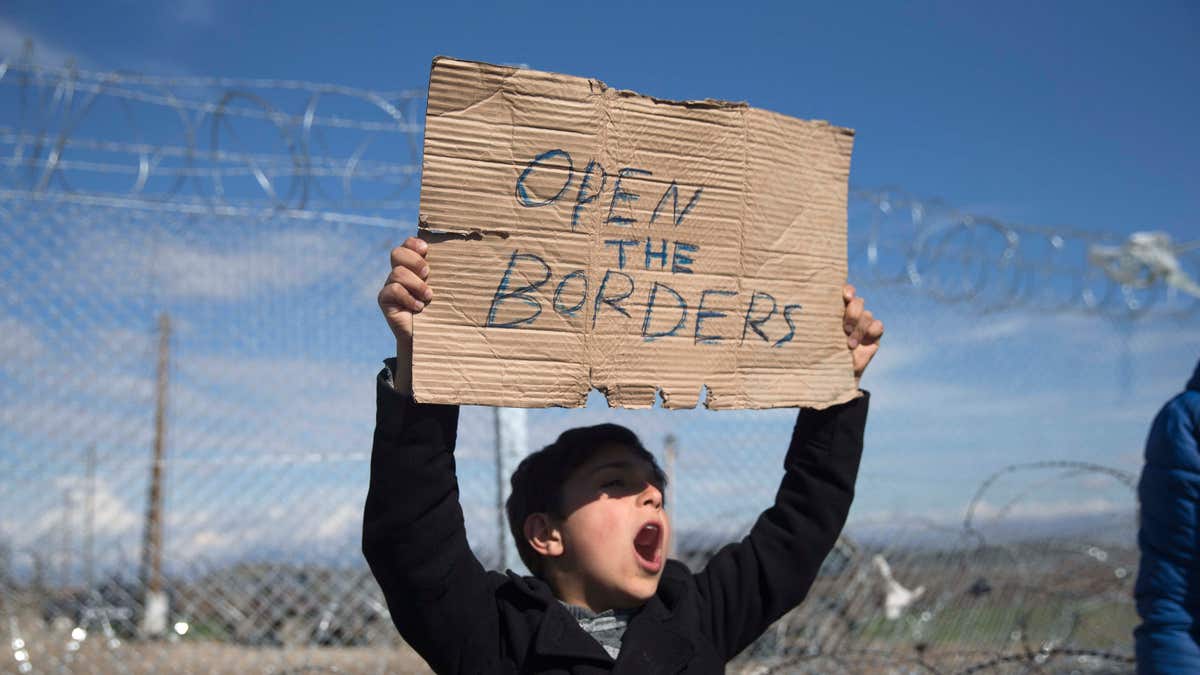

Feb. 27, 2016: A boy shouts slogans as he holds a placard during a protest by refugees and migrants in front of the wire fence that separates the Greek side from the Macedonian one at the northern Greek border station of Idomeni. (AP)

ATHENS, Greece – Greece is fast becoming the "warehouse of human beings" that its government has vowed not to allow.

Hastily setup camps for refugees and other migrants are full. Thousands of people wait through the night, shivering in the cold at the Greek-Macedonian border, in the country's main port of Piraeus, in squares dotted around Athens, or on dozens of buses parked up and down Greece's main north-south highway.

On Thursday, hundreds of frustrated men, women and children abandoned their stranded buses or left refugee camps, setting off on a desperate trek dozens of kilometers (miles) long to reach a border they know is quickly shutting down to them.

About 20,000 migrants were in Greece on Thursday, Defense Minister Panos Kammenos said. Of those, Macedonia allowed just 100 people to cross over from Greece's Idomeni border area.

By late Friday, not a single migrant had crossed into Macedonia that day, while 4,900 people waited nearby in heavy rain, according to Greek police.

Thousands more were heading north — about 40 busloads of people were waiting along Greece's main highway, while refugee camps in northern Greece and near Athens were full.

Greece is mired in a full-blown diplomatic dispute with some EU countries over their border slowdowns and closures. Those border moves have left Greece and the migrants caught between an increasingly fractious Europe, where several countries are reluctant to accept more asylum-seekers, and Turkey, which has appeared unwilling or unable to staunch the torrent of people leaving in barely seaworthy smuggling boats for Greek islands.

Adding to the pressure is Greece's financial predicament. The country has been wracked by a financial crisis since 2010 and still depends on an international bailout for which it must pass yet more painful reforms. Those have led to widespread protests, including blockades on the country's highways by farmers who are furious at pension changes.

The vast majority of those reaching Greece, Europe's main gateway for migrants, have been Syrians, Afghans and Iraqis fleeing war at home

"My only hope is to live in a safe place. That's enough for me actually," said 17-year-old Minhaj Ud Din Wahaj from Afghanistan's Wardak province. "We have been in war since 40 years, so I have been raised in war."

In Athens, hundreds of migrants mill around central Victoria Square, uncertain of where to go next. On Thursday, two men hanged themselves from a tree in the square but were rescued by bystanders. Police said the men were trying to draw attention to their predicament.

In the north, nearly 400 people scrambled out of a former military base set up as a refugee camp in Diavata, near the city of Thessaloniki, and began walking the 70 kilometers (43 miles) to Idomeni on the Macedonian border. Dozens more set off on foot from buses stuck on the highway, where farmers' blockades were hindering traffic.

Still more people flowed into the country, with dinghies full of migrants arriving on Greece's islands and hundreds more people piling on ferries heading to the main port of Piraeus.

"We are escaping from war," said Rana, an English teacher from Syria arriving in Piraeus. She would not give her last name to protect those she left behind. "Our house is destroyed, and salaries in some places stopped. ... I think all the people ... seek the shelter and education for their kids."

But Europe appears increasingly unwilling to provide those basics.

On the weekend of Feb. 20-21, Macedonia stopped allowing Afghans through. Other countries further up the line appeared to do the same. On Thursday, even Syrians and Iraqis were being allowed to cross over from Greece only at a trickle. Nadica V'ckova, a spokeswoman for Macedonia's crisis management department, told The Associated Press that Macedonia was restricting the entry of refugees to match the number leaving the country.

Bitter sniping has ensued between Greece and other EU members as Greece insists the EU's 28 nations share the refugee burden equally.

"Greece, from now on, will not assent to agreements if the proportionate distribution of the burden and responsibility among all member states is not rendered obligatory," Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras told Parliament on Wednesday.

"We will not accept the transformation of our country to a permanent warehouse for human beings, while at the same time we continue to operate in Europe and at summit meetings as if nothing is happening," he declared. "We will not put up with a series of countries that not only erect fences on their borders but at the same time do not accept to put up a single refugee."

Athens was enraged when Austria held a meeting of Balkan countries Wednesday on the refugee crisis, excluding Greece. It recalled its ambassador in Vienna the next day.

Greece's minister responsible for migration, Ioannis Mouzalas, had harsh words as he arrived for a Thursday migration meeting in Brussels.

"(Many here) will try to discuss how to respond to a humanitarian crisis in Greece that they themselves are intent on creating," Mouzalas said. "Greece will not accept unilateral actions. Greece, too, can take unilateral action."

Peter Szijjarto, Hungary's minister of foreign affairs and trade, didn't mince his words in response.

"Blackmailing is not a European attitude," he said. "Maybe Greece, too, should observe our common rules, or at least accept help to observe them together. Then we do not have to face such challenges."

While the politicians wrangle, the refugees still stream in, risking their lives across the winter seas in the hopes of a better future.

"If the border closes over there, there will be possibilities, but it may cost a lot of money, not only for me, for everybody," said Jamshid Azizi, a 24-year-old Afghan who once worked as an interpreter for international forces in his homeland.

Many of his friends were already talking to smugglers, but not him.

"I prefer to stay here, because I don't have that amount of money to pay for human traffickers in order to pass the borders," he said.